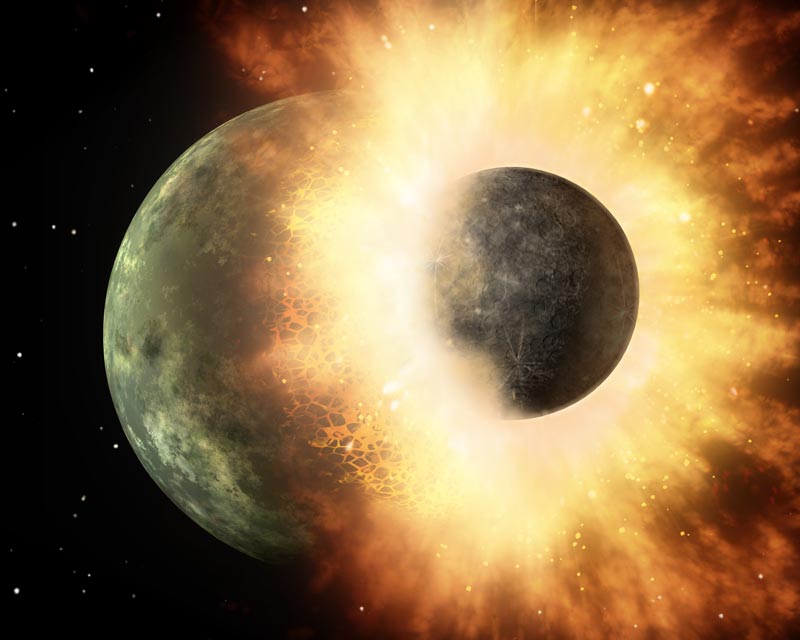

Two Worlds Collide in Deep Space

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Two distant planets orbiting a young star apparently smashedinto each other at high speeds thousands of years ago in a cosmic pileup ofcataclysmic proportions, astronomers announced Monday.

Telltale plumes of vaporized rock and lava leftover from thecollision revealed its existence to NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, whichpicked up signatures from the impact in recent observations.

The two-planetpileup occurred within the last few thousand years or so - a relativelyrecent cosmic timeframe. The smaller of the two bodies - a planet about thesize of Earth's moon, according to computer models - was apparently destroyedby the crash. The other was most likely a Mercury-sized-planet and survived,albeit severely dented.

"This collision had to be huge and incrediblyhigh-speed for rock to have been vaporized and melted," said Carey Lisseof the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, leadauthor of a paper describing the findings in the Aug. 20 issue of theAstrophysical Journal.

Researchers believe the planets were moving at about 22,400mph (10 kilometers per second) before the crash. The violentwreck released amorphous silica rock, or melted glass, and hardened chunksof lava called tektites. Spitzer also spotted large clouds of orbiting siliconmonoxide gas created when the rock was vaporized.

?"This is a really rare and short-lived event, criticalin the formation of Earth-like planets and moons," Lisse said. "We'relucky to have witnessed one not long after it happened."

Infrared detectors on Spitzer found the traces of rockyrubble and re-frozen lava around a young star, called HD 172555, still in theearly stages of planet formation. The system is about 100 light-years fromEarth. One light-year is the distance light travels in a year six trillionmiles (9.7 trillion km).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A similar fender-bender is thought to have formedEarth's moon more than 4 billion years ago, when a body the size of Marsrammed into Earth.

"The collision that formed our moon would have beentremendous, enough to melt the surface of Earth," said co-author GeoffBryden of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. "Debris from thecollision most likely settled into a disk around Earth that eventuallycoalesced to make the moon. This is about the same scale of impact we're seeingwith Spitzer - we don't know if a moon will form or not, but we know a largerocky body's surface was red hot, warped and melted."

In fact, such violent encounters seem to have been common inour own solar system's early history. For example, giant impacts are thought tohave stripped Mercury of its outer crust, tipped Uranus on its side, and spunVenus backward.

As recently as last month, a small space rock slammedinto Jupiter, making a large black bruise.

In general, rocky planets like Earth coalesce and grow whensmall rocks crash and clump together, merging their cores.

The system around HD 172555 is a relative baby at only 12million years old, compared to our solar system's age of 4.5 billion years.

- Video - When Worlds Collide

- 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.