Giant Storms Erupt on Jupiter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

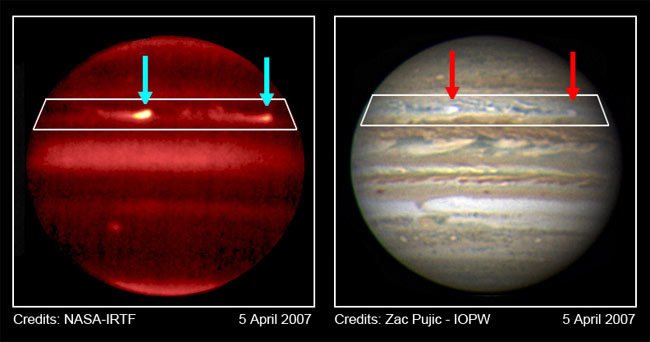

Two giantplumes erupted recently on Jupiter, moving faster than any other Jovian featureand leaving global streaks of red cloud particles in their wake.

New analysesof the March 2007 outbursts suggest internal heat plays a significant role ingenerating such weather patterns.

Theresults, detailed in the Jan. 24 issue of the journal Nature, shed lighton the inner workings of Jupiter'sweather. Planetary scientists and meteorologists have puzzled over whetherinternal heat or sunlight (or both) powers Jupiter's stormy disturbances andjets.

Similarphenomena occurred in 1975 and 1990, but the most recent event has never beenobserved before with high-resolution modern telescopes.

Jovianoutbursts

A team ofastronomers monitored the development of the cloud activity in March 2007 usingNASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaiiand telescopes in Spain's Canary Islands.

The twoplumes erupted at middle northern latitudes, about 39,150 miles (63,000kilometers) away from each other and raced across the planet at more than 375 mph(600 kph). The astronomers watched as each of the plumes mushroomed from its initial diameterto a whopping 1,245 miles (2,000 kilometers) in about a day.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Slowermoving dark patches and bright features were shed in the wake of the plumes. Inparticular, the systems left behind a turbulent planetary-scale disturbancecontaining red cloud particles.

The chemical makeup and formation of these red aerosols is a bit of a mystery itself. "Nobody knows what its composition is," said lead study author Agustin Sanchez-Lavegaof Universidad del Pais Vasco in Spain, "although in the Jovian atmosphereit is seen in the Great Red Spot and other smaller vortices," he told SPACE.com.

Consideredthe most powerful storm on Jupiterand perhaps in the entire solar system, the Great Red Spot spans twice as wideas our planet and is at least 300 years old.

Weathermaker

Using theirobservations and computer models, the astronomers found the bright plumesformed in Jupiter's deep water clouds and then shot ice particles and waterwell above the visible clouds.

"Theinfrared images distinguish the plumes from lower-altitude clouds and show thatthe plumes are lofting ice particles higher than anyplace else on theplanet," said study researcher Glenn Orton of NASA's Jet PropulsionLaboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Theresearchers also found that despite the turmoil created as the plumes churnedthrough the jet stream, once the plumes waned, the planet's jet stream remainednearly unchanged. This observation, along with computer models, suggests thejet stream extends more than 62 miles (100 kilometers) below the cloud topswhere most sunlight gets absorbed.

Sincesunlight is minimal there, the researchers say the results support the ideathat Jupiter's jets are powered by internal heat. This hypothesis was firstproposed based on 1995 observations made when the Galileo probe descendedthrough Jupiter?supper atmosphere.

That'sunlike what happens on Earth, where sunlight drives all weather. But for theouter planets, where the sun's reach can be minimal, a planet's internal heatmight play a substantial role. At the extreme, distant Neptune releases twiceas much heat as it takes in from sunlight, and it boasts winds reaching 1,500 mph(about 2,400 kph). The release of heat is part of the natural cooling of aplanet, a process that begins at birth when a planet is at its hottest.

?All theevidence points to a deep extent for Jupiter's jets and suggest that theinternal heat power source plays a significant role in generating thejet," Sanchez-Lavega said.

Theastronomers found striking similarities between the March event and the twoprevious eruptions in 1975 and 1990. All three eruptions occurred with aperiodic interval of about 15 to 17 years. In all three events, the plumesalways appeared in the jet peak and moved at the same speed. In addition, thedisturbances erupted with exactly two plumes each time.

Scientistssay the Jovian findings could have implications for understanding weather onEarth, where storms are also frequent and jet streams determine large-scalewind patterns.

- Video: Follow New Horizons on its Jupiter Flyby

- The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Image Gallery: Jupiter's Moons