Newfound Ice World Alters Perceptions of Planetary Systems

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

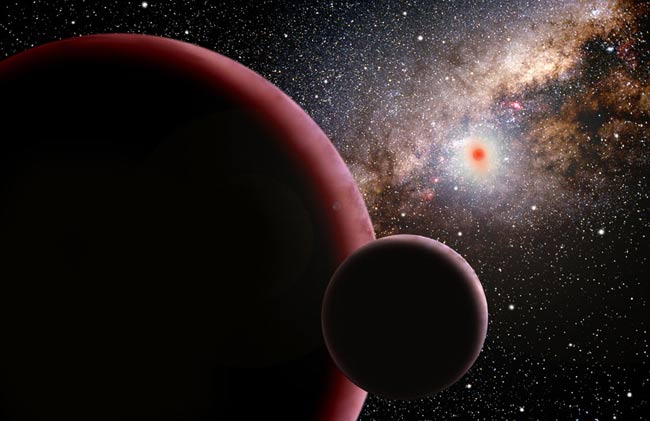

Astronomers announced today the discovery of a frigid extrasolar planet several times larger than Earth orbiting a small red dwarf star roughly 9,000 light years away.

The finding alters astronomers' perceptions of planetary system formation and the distribution of planets in the galaxy, suggesting that large rock-ice worlds might outnumber gas giants like Jupiter.

The newfound planet is about 13 times more massive than Earth and likely has an icy and rocky but barren terrestrial surface, and it is one of the coldest planets ever discovered outside of our solar system.

It orbits 250 million miles away from a red dwarf star, which is about half the size of our Sun and much cooler. The orbital distance is about the same as our solar system's asteroid belt is from the Sun.

Rocky and cold

The planet is similar in rocky structure to Earth and it is described a "super-Earth."

But being so far away from a red dwarf means that its surface temperature is an inhospitable -330 degrees Fahrenheit (-201 Celsius), about the same as Uranus. That's too cold for liquid water or life as we know it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Further analysis of the system revealed the absence of Jupiter-like gas giants, and scientists suspect the system literally ran out of gas and failed to form any. This may have starved the newfound planet of the raw materials it needed to turn into a gas giant itself.

"This icy super-Earth dominates the region around its star that in our solar system is populated by the gas-giant planets, Jupiter and Saturn. We've never seen a system like this before, because we've never had the means to find them," said study author Andrew Gould of The Ohio State University and leader of the MicroFUN planet-searching team.

'Pretty common'

Planet formation theory predicts that small, cold planets should form easier than larger ones around big stars. A previous study suggests that about two-thirds of all star systems in the galaxy are red dwarf stars, so solar systems filled with super-Earths might be three times more common than those with giant Jupiters.

"These icy super-earths are pretty common," Gould said. "Roughly 35 percent of all stars have them."

While this is one of the coldest exoplanets ever discovered, it is not the smallest. Earlier this year astronomers announced the discovery of an exoplanet just 5.5 times Earth's mass. The previous record holder weighed in at 7.5 Earth masses.

"Our discovery suggests that different types of solar systems form around different types of stars," said Scott Gaudi of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "Sun-like stars form Jupiters, while red dwarf stars form super-Earths. Larger A-type stars may even form brown dwarfs in their disks."

Brown dwarfs are dim, failed stars that straddle the mass range between gas planets and real stars.

Discovery details

Astronomers discovered this latest planet, catalogued as OGLE-2005-BLG-169lb, with a technique called microlensing, an effect where the gravity of a foreground star makes a more distant star appear brighter. If the foreground star is orbited by a planet, the planet's gravity can periodically warp the brightness of the background star by tiny amounts.

This shift is a telltale indicator of a planet, but is so brief that scientists must monitor the star closely and make multiple observations to confirm the planet's existence. In this case, the scientists were concerned that the warp wasn't caused by a planet, so they wrote a special computer program to speed up their models and confirm the existence of the Neptune-sized object.

The planet's existence was determined by researchers from the MicroFUN, OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) projects and the MDM Observatory in Arizona. The group has submitted their findings for publication in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

- The Growing Habitable Zone: Locations for Life Abound

- Small Rocky Planet Found Orbiting Normal Star

- Star Search Finds Neighborly Red Dwarf

- Earth's "Bigger Cousin" Detected