Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomersannounced today the discovery of what is possibly the smallest planet knownoutside our solar system orbiting a normal star.

Its orbit isfarther from its host star than Earth is from the Sun. Most known extrasolarplanets reside inside the equivalent of Mercury's orbit.

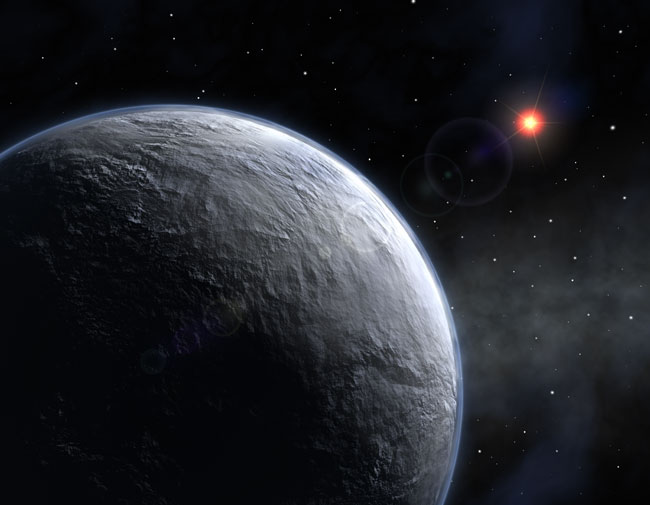

The planetis estimated to be about 5.5 times as massive as Earth and thought to be rocky.It orbits a red dwarf star about 28,000 light-years away. Red dwarfs are aboutone-fifth as massive as the Sun and up to 50 times fainter. But they are amongthe mostcommon stars in the universe.

Article continues belowSo thefinding suggests rocky worlds may be common.

"Theteam has discovered the most Earth-like planet yet," said Michael Turner, assistantdirector for the mathematical and physical sciences directorate at the NationalScience Foundation, which supported the work.

Thediscovery is detailed in the Jan. 26 issue of the journal Nature.

More tocome

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Priorto this discovery, the smallest extrasolar planet found around a normal starwas about 7.5 Earthmasses. Earth-sized planets have been detected, but only around dyingneutron stars.

Thenewfound planet, named OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb, is probably too cold to supportlife as we know it, astronomers said. With a surface temperature of -364degrees Fahrenheit (-220 degrees Celsius), it is nearly as frigidas Pluto.

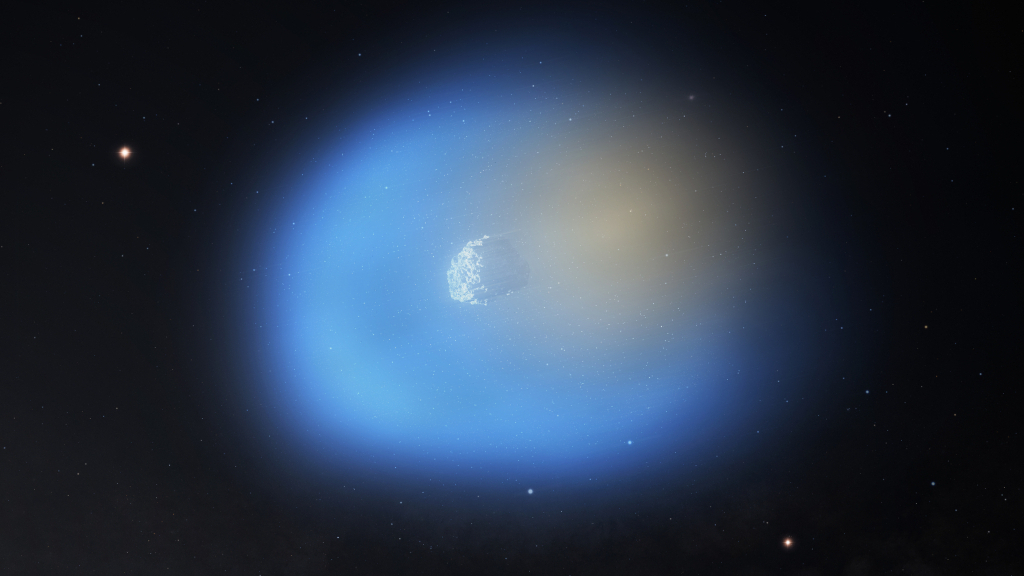

Itwas discovered using a technique called "gravitationalmicrolensing," whereby light from a distant star is bent and magnified bythe gravitational field of a foreground star. The presence of a planet aroundthe foreground star causes light from the distant star to become momentarilybrighter.

Astronomershailed the discovery as the first of a new class of small, rocky worlds locatedat far-out distances from their stars.

The planetand star are separated by about 2.5 astronomical units (AU). One AU is equal tothe distance between the Earth and the Sun. Until now, no small planet had beenfound farther than 0.15 au from its parent star.

Thefinding means planet hunters are one step closer to detecting their holygrail: a habitable Earth-like planet that can sustain liquid water andsupport life.

"Wemay predict with reasonable probability that microlensing will discover planetswith masses like that of Earth at a similar distance from their stars and withcomparable surface temperature," said study co-author Bohdan Paczynski from Princeton University.

Newoutlook

Of the morethan 150 planets have been discovered so far, most were found using the Dopplertechnique, in which astronomers look for wobbles in a star caused by thegravitational pull of a planet. This method has uncovered dozens of huge worldsbut can't spot small planets that are far from their stars.

Microlensingcan detect small planets, but it is 50 times more likely to find a gas-giantplanet like Jupiter.

"Microlensingshould have discovered dozens of Jupiters by now if they were as common asthese five-Earth-mass planets," said study co-author David Bennett.

Thatsuggests most of our galaxy's planets are small and rocky.

Thisprediction agrees with the standard model for solar system formation, known asthe "coreaccretion" model. It goes like this: Dust around newborn stars forms clumpsthat stick together and eventually become asteroids, comets and planetprecursors. In this scheme, relatively few planets successfully become gasgiants, and they are outnumbered by small, rocky worlds.

"It'sincredible to think that we went from 10 years ago having no planet to nowhaving over 100 gas giants and even starting to find the first terrestrialplanets," said Alan Boss, a theorist at the Carnegie Institution of Washingtonwho did not participate in the discovery. "That's just an amazing leap."

Shortcoming

Since staralignments are unique events, a microlensing experiment can never be repeated.Todd Henry, an astronomer at Georgia State University who was not involved inthe study, said the discovery was an "intriguing result from this particulartechnique, but unfortunately you can't follow it up."

Manyastronomers view the lack of repeatability as an acceptable trade-off, however,because thousands of star systems can be screened in a relatively short periodof time compared to other techniques.

"You can'tlearn a whole lot about the details of individual systems ... but it's awonderful alternative for learning about what the mass distribution ofextrasolar planets might be and the frequency at which they occur," said DavidLatham, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics whowas not part of the study.

In atelephone interview, Jean-Phillipe Beaulieu, a co-author in the study, saidthat while the observations can never be repeated, the discovery wassimultaneously verified by different telescopes around the world.

Themicrolensing event was detected July 11 by telescopes in the OGLE(Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) project. Planet-hunters are veryprotective of their data and cooperation between different teams is rare. Butastronomers around the globe were alerted so the event could be detected bymultiple telescopes.

"The onlyway to realize the full scientific benefit of our observations is to share thedata with our competition," said Paczynski, an OGLE co-founder.

Overall,the study involved 73 researchers from 32 institutions worldwide.

"The factthat they've got a whole bunch of folks using multiple telescopes all observingthe same event and calibrating themselves self-consistently makes the data lookvery sound," Boss said. "I think it's a pretty solid detection."

- Earth's "Bigger Cousin" Detected

- 'Super Earth' Discovered at Nearby Star

- Strange New World Unlike Any Other

- Several Extrasolar Planets Suspected Near Center of Galaxy

- Astronomers on Brink of Watershed in Planet Discoveries

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.