Europa or Mars: Where Could Extraterrestrial Life Be Found First?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A dusty redplanet and an icy moon of Jupiter may hold the best hopes for scientists tryingto track down extraterrestrial life, at least in this solar system.

Mars andEuropa each hold the promiseof liquid water and possibly life. Mars has a history that suggests wateronce flowed in rivers and lakes, and it may still harbor liquid water deepunderground. The more distant Europa could hide a churning ocean filled withlife forms beneath its icy surface, as the moon gets gravitationally squeezedby Jupiter.

Futurespace missions have targeted both destinations to send new robotic explorers.But the red planet represents a much closer and better known target for spaceexplorers.

"We'remuch farther down the road with Mars than Europa," said Jack Farmer, anastrobiologist at the University of Arizona.

Marsinvites a deeper look

Liquidwater probably once filled the valleys and basins on Mars, but now the planet'ssurface resembles a barren, dusty badland. Any living organisms that may haveexisted must have gone extinct or underground.

"Myview is that habitableenvironments on Mars are likely to only be found in the deeper subsurfacewhere we might have a hydrosphere," Farmer told SPACE.com."Liquid water is unstable at the surface of Mars today."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Some icewater or snowfall could temporarily become liquid at the surface, such as whenNASA's Phoenix Mars Lander possibly found some liquefied globules clingingto its struts. Still, that would hardly last long enough under freezing orvaporizing conditions to sustain life.

Microbiallife that could eke out an existence also seems unlikely to survive the cosmicradiation that scours the surface of Mars. But astrobiologists remain excitedabout possibly finding signs of past life on the surface, where minerals thatonly form in water may have preserved certain remains.

"A lotof these kinds of mineralogical targets are water indicators, and we know wherea lot of these deposits are now," Farmer said. He noted that sulfate mineralsdo a decent job of preserving organic compounds produced by organisms on Earth,and sometimes even microfossils. Silica and other clay minerals have alsoturned up during searches by the Mars rovers and orbiters.

Upcomingmissions to Mars could perhaps even tap into any liquid reservoirs hiddendeeper below and search for existing life, if they have the rightequipment.

Europa'socean: fact or fiction?

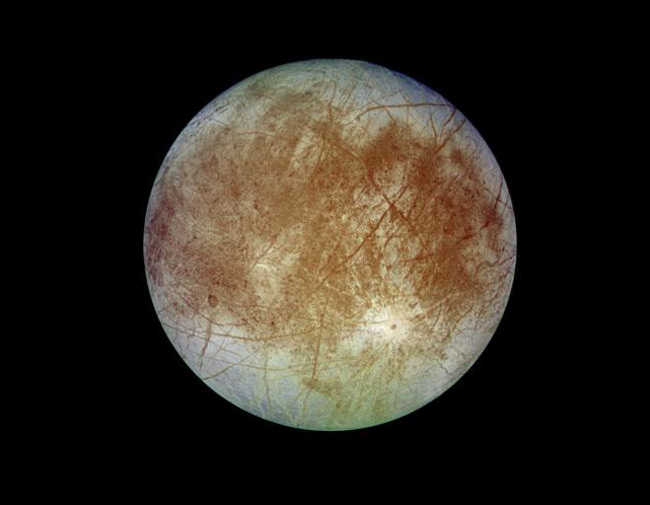

A morechallenging target for astrobiologists sits farther out in the solar system,where the icy moon Europa beckons with hints of a salty ocean beneath itscrusty exterior.

"Europa'sa very appealing target for astrobiology, and particularly from the standpointof what life forms might be working in a sub-surface ocean," Farmer noted."The challenge with Europa is that we don't know for sure if there's asub-surface ocean."

Somestudies have suggested that Europa holdsan ocean up to three times deeper than Earth's oceans. But other modelshave suggested that no such ocean exists, and that perhaps the moon onlyharbors pockets of ice-brine slush. The debate largely depends on how much heatEuropa can generate from tidal flexing, when Jupiter squeezes the moon with itsgravitational pull.

Still,Farmer suggested that life could perhaps exist even within a "snowballslush" mixture between the solid ice chunks. Such slush appears to haveerupted onto the moon's surface at times due to icy volcanic eruptions, and anymaterial that came up might have carried signs of life with it ? althoughliving organisms would perish quickly due to the harsh radiation bombardment atthe moon's surface.

"Ifyou drop down a ways below the depth where radiation is affecting surfacematerials, you might be able to access biosignatures frozen out in the icethere," Farmer said.

A recentstudy suggested that Europa may hold hundreds of times more oxygen thanscientists had previously imagined. That has lent to the sense of optimismabout prospects for life on the slush ball.

Send inthe robots

Still otherworlds may beckon just as strongly as Mars or Europa, such as Saturn's icy moonEnceladus. Yet the race to find extraterrestrial life may ultimately come downto where humans decide to send the robots.

Plannedmissions or mission proposals exist for the robotic exploration of both Marsand Europa. NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) is slated to put an SUV-sizedrover down on the red planet after launching in late 2011, and has an onboardorganic chemistry lab that can do a general assessment of surface conditions.That would represent a "baby step for an actual life detectionmission," Farmer said.

TheEuropeans also continue to refine their ExoMars rover concept that could go astep farther and actually drill down into Martian regolith. A successfulbiosignature reading would likely lead to a mission to return Martian samplesto Earth, where scientist could run definitive tests. Farmer sees this as areal possibility within the next decade.

Europa mayultimately lag behind Mars in the ongoing search for life, if only because itrepresents a greater unknown and poses steeper mission challenges.

"Ifyou were going to look for life on convecting snowball, you're going to use adifferent kind of approach than if you were going to penetrate an ocean threetimes deeper than any on Earth," Farmer pointed out. The extreme differentviews of Europa each require very different mission approaches.

A jointmission between NASA and the European Space Agency would likely first send anorbiter to better examine Europa, and perhaps figure out whether a sub-surfaceocean truly exists to warrant deep drilling. But that won't likely launch until2020 at the earliest. And besides, scientists may not yet have the technologyto create a lander capable of surviving Europa's harsh surface environment.

"Youwould have to land on surface with no real atmosphere, freezing temperaturesand high radiation, and survive there while you drill," Farmer said."We can't do that yet."

- Video - Return to Jupiter and Europa

- Out There: Water, Water Everywhere

- SPACE.com Video Show - Rover Tracks on Mars

Editor's Note:This feature articleis part of SPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.