Space Cooking: Feeding Astronauts on Mars-bound Missions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

While NASA engineers toil away with spacecraft designs to determine how humans will explore the moon and Mars, other researchers are developing devices to help future astronauts feed their hunger.

Future long-duration space crews may need up to 40 different food processing machines to turn crops such as wheat and tomatoes into edible foods like bread and cereals, NASA officials estimated.

"As we go on to longer-duration missions, it makes sense to become a little more self-sufficient with our food," said Michele Perchonok, a food scientist at NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, in a telephone interview. "The ultimate way of doing that is growing crops and processing them into food."

But the challenge lies in keeping space food equipment small, light and easy to maintain during a two-year Mars trip, said Perchonok, the advanced food technology lead for the National Space Biology Research Institute at JSC.

"Some of the other challenges reside in making sure the food that is produced is safe, nutritious and acceptable," she added.

In-flight meals

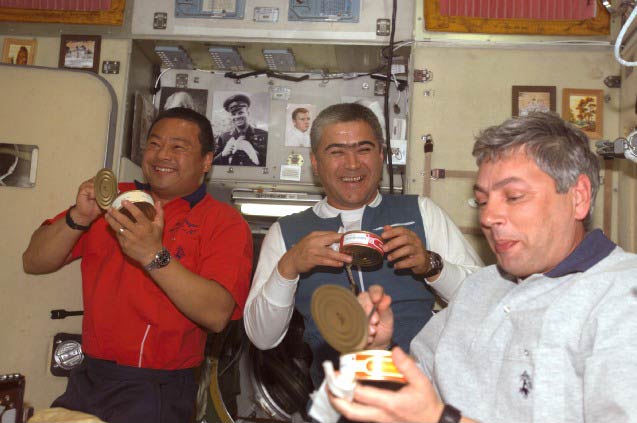

Aboard the International Space Station (ISS), astronauts eat ready-made meals out of cans and pouches with a limited supply of fresh fruits and vegetables shipped up periodically aboard Russian supply ships. Coffee, tea, Tang and other beverages are typically in dried form to be mixed with water.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Most food items are pre-cooked on Earth before being shipped to the refrigerator-less ISS galley in the Russian Zvezda service module, where astronauts can warm food using an electric oven.

"It's about the size of a briefcase, and there are little slots where you can put the food," Perchonok said of the oven, adding that it doesn't get too hot.

Ohio State University food engineer Sudhir Sastry has developed a prototype for reheating food in space by including the heater directly into an items packaging. Sastry equipped a package with electrodes in order to warm up food using a method called ohmic heating.

"Basically you're passing a current through the food product itself to heat it up internally," Sastry told SPACE.com, adding that once the meal is consumed the package can be reused to sterilize biological waste and other refuse. "It's better food quality from the get go."

Food engineer Paul Singh, of the University of California at Davis, built a prototype device that processes tomatoes into pretty much any form needed for a meal during a mission to Mars to beyond.

"It's a tomato processing plant, a benchtop device that slices, dices cuts and purees," Perchonok said, adding that a space food processor must be both multi-purpose and miniaturized.

For his part, ISS Expedition 10 flight engineer Salizhan Sharipov - currently living aboard the space station - said before launch that he would miss cooking in his own kitchen during the six-month mission but looked forward to life in orbit.

Greenhouse effects

Astronauts on a future Mars-bound spacecraft will also likely also grow at least some of their food. But finding the right mixture of crops and understanding their effects on both crew and spacecraft are necessary concerns.

"It's probably two issues that we're concerned with," Paul Larrat, a University of Rhode Island researcher, told SPACE.com. "One is what these compounds will do to humans in space environments and they other is what they'll do to other plants."

Larrat worked with Advanced Life Support Center scientists at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida to determine how small amounts of gases emitted by plants can affect their spacecraft surroundings.

"It's more than just turning carbon dioxide into oxygen," Larrat said. "There are minute quantities of other gases that on Earth you'd never think about."

On Earth, those gases would simply dissipate in the wide open sky, but not aboard an enclosed spacecraft.

The gases from lettuce, for example, may hinder the growth of radishes and impact the food source from within, Larrat said. Meanwhile, a future Mars crew would be living in close quarters with its food supply, so astronauts would have to be carefully screened for allergens to make sure they weren't allergic to any of the onboard plants, he added.

Perchonok said NASA researchers are also tackling other food fronts, including plans to grow peanuts and soy to extract oil and culling syrup from sweet potatoes as an alternative to stocking up on sugar before a long-duration launch.

Interesting eats

Keeping astronauts interested - and satisfied - with their food is another prime target for current and future missions.

"They can't just go out and pick up something they want," Perchonok said. "They can't just go to McDonald's."

Admittedly, space food was rather primitive in NASA's early days, leaving much to be desired in both appearance and taste, researchers said.

"They started with tubed foods squeezed out like toothpaste and cubes that were like sandwiches coated in gelatin," Perchonok said. "But the flavor...well, you're at that psychology where it didn't feel like food anymore."

By the later Gemini and Apollo missions, the space agency had shifted to what most people consider real food, leading to the preparation systems aboard the space shuttle and ISS today. Using astronaut taste testers, NASA food researchers add between three and six new items a year to the agency's space menu.

"I think we can go a lot further than where we are now," Perchonok said, adding that still more improved food packaging and processing have yet to be developed. "There's a lot for us to do, and we're going to go forward and do it."

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.