Cosmic Clean-Up: Wild Ideas to Sweep Space

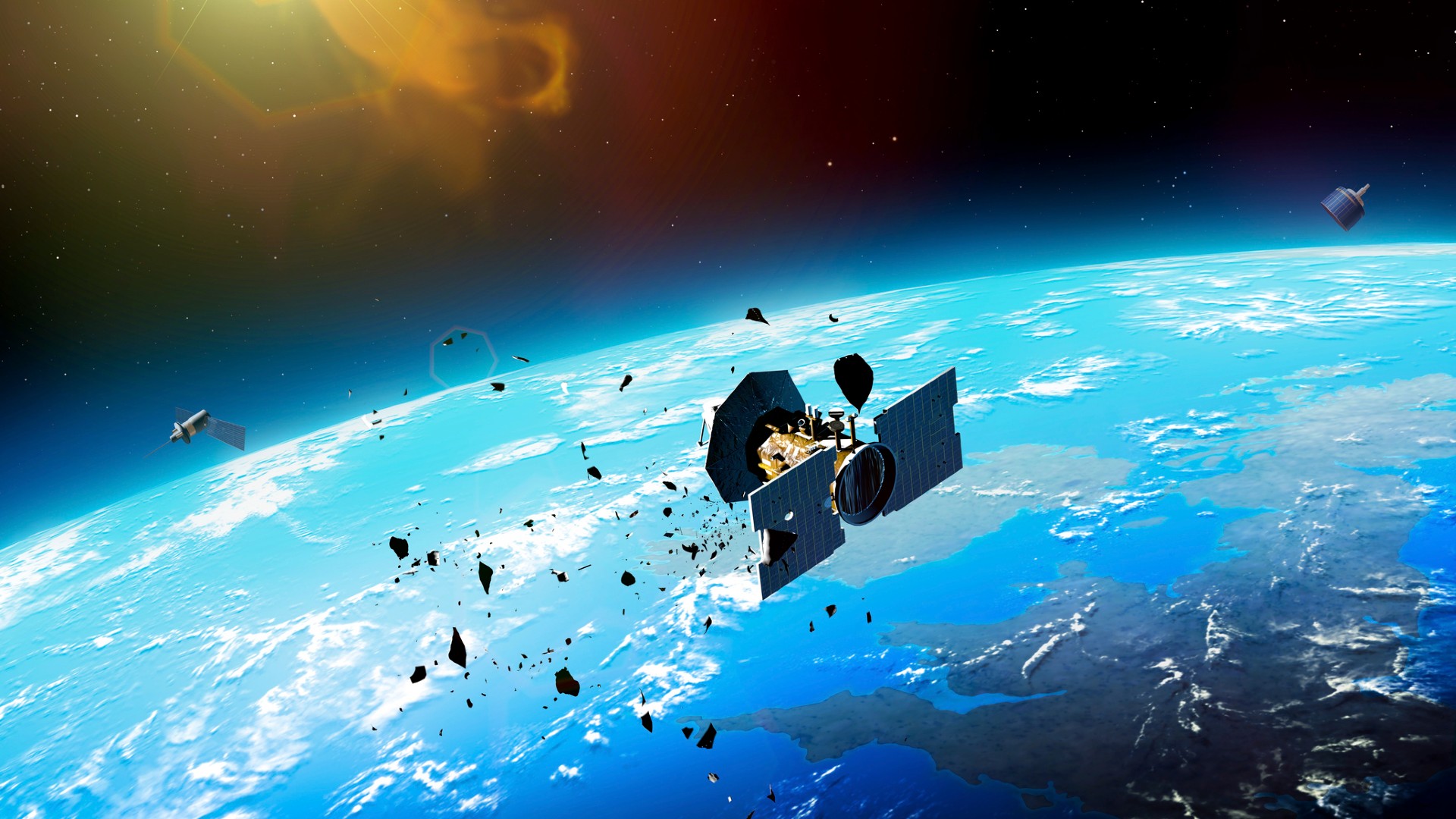

Space islittered with millions of bits of orbiting garbage leftover from missions. Theflying flotsam can delay launches and could potentially smash into spacecraft. Nowsome creative ideas are emerging for how to sweep up the junk. One idea even involvesan oversized NERF ball.

Thegraveyard of ghostly scraps from satellites and other craft continues to grow.Last year, the intentional destruction of China's Fengyun-1Cweather satellite sent at least 150,000 bits of orbital debris less than ahalf-inch (one centimeter) across and larger into space, according to NASA'sOrbital Debris Program.

On Feb. 20,another load of debris was scattered into space when the U.S. Navy shot down a waywardspy satellite above the Pacific Ocean. Some 3,000 scraps spewed into space,each no larger than a football in size, adding to the cosmic clutter.?

Thetrashiest region of space lies within low Earth orbit, located at 1,243 miles(2,000 kilometers) above the Earth's surface. Space junk can also be found to alesser degree in geosynchronous orbit?situated higher at 22,235 miles (35,785km) above the Earth.

The U.S.Space Surveillance Network is tracking about 18,000 orbiting objects of debrisabout two inches (five centimeters) in diameter and larger.

The spacearound our planet is also polluted by millions to tens of millions of smaller,marble-sized pieces of debris. In order to officially catalog derelict debris,scientists involved need to identify each object's size, the mission it'sattached to and its orbit.

Because thetrash zips around the planet at around 4 to 5 miles per second (7 to 8kilometers per second) at least in low Earth oOrbit, the physical makeup of spacedebris ? especially those pieces that are five centimeters and larger ? isnot really important.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

?It couldbe made out of Jell-O or foam or stainless steel. When it's that big, ittravels at orbital velocities and it hits something else, it's going to be abad day,? said Nicholas Johnson, program manager and chief scientist of theNASA Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston,Texas.

Ideas fortidying up space range from the mundane, such as space tethers, to the exotic,such as trash-truck-like craft. Johnson says, however, that none of theproposals are feasible as yet.?

Trashpile-up

Rather thanclogging up waterways and landfills like Earthly litter does, space debris hasthe potential to bang up working spacecraft along with their crews.

Todate, there is only one recorded incident of a collision in which the debriswas large enough to track. In 1996, a French satellite called CERISE was struckby a piece of a French rocket that had exploded 10 years earlier.

Normally,spacecraft can use information from tracking systems to dodge and avoid thesecollisions with larger objects. But small pieces of orbitaldebris routinely smash into and ding spacecraft, such as the space shuttle.

"It'snot a near-term operational issue," Johnson said. "But it issomething that, like any environmental problem, if you ignore it, it will getmuch worse and it could get to the point where remediating the environment ismuch more difficult and expensive than simply preventing it from becoming sobad."

To makematters worse, debris eventually begets more debris. Bits of space junkconstantly collide with their neighbors, with the current smash-ups involvingsmall pieces hitting larger vehicles and producing little extra debris. Butthat could change.

"It'sa regeneration process that is going to happen,? Johnson told SPACE.com.?The only way to prevent it would be to go up there and start removing theselarge derelict spacecraft and launch vehicles."

Litterbugs

Debriscollisions are just a piece of the trash pie. Accidental explosions of oldrocket bodies and other vehicles are the main contributors to debris in space.While not the primary litterbugs, spacecraft at the end of their lives cancontribute to cosmic trash. Currently, the international space community hasfollowed guidelines for preventing accidental explosions as well as forend-of-life disposal. That means removal of spacecraft from low Earth orbitwithin 25 years of their launch. Craft in geosynchronous orbit nearing old ageget bumped into a higher orbit, where they won't interfere with other geosynchronous-orbiting satellites.

Even so,last year set a new record for the amount of space debris.

"Theprinciple reason was the Chinese anti-satellite test," Johnson said."That event alone far exceeded the debris generated in any other year,ever. Unfortunately, it's very long-lived debris; it will be up there fordecades or even a century or more."

Cosmiccollectors

Theinternational space community, Johnson said, has brainstormed and experimentedin efforts to concoct a way to clean up the graveyardof space for the past 20 years or so. "We haven't found a singleconcept which is both technically feasible and economically viable,"Johnson said. "In the future if launch costs go down dramatically, whichwe always hope will happen but never does, or if we come up with newtechnology, the equation may change and all of a sudden a previous concept thatwas not viable could become viable."

Johnson isco-author of a new report set for publication next year that details a reviewof "clean-up concepts.? Ideas range from the relatively mundane to the exotic,though none "meet all the requirements for a viable remediationtechnique," Johnson said.

One of hisfavorite ideas involves launching a giant NERF ball spanning a mile (1.6 km)across, which would sort of field the orbiting debris. As small particles passthrough the foamy ball, they would lose energy and fall back to Earth morequickly.

Raining onthis sporty idea, however, are technical issues. "The NERF ball itselfwould fall out of orbit pretty quickly, because it's so lightweight relative toits size; and it's non-discriminatory, so it could accidentally run intooperational spacecraft and that's not a good idea," Johnson said.

Someother ideas

Ground-basedor space-based lasers could also perturb orbits and push the junk to loweraltitudes so they would fall back to Earth quicker. (The glitch: Lasers arevery expensive and limited in the number of objects they can interact with.)

Trash-collectorvehicles could rendezvous with a chunk of debris and latch onto it beforedragging it into a lower orbit, or higher orbit, depending on its currentlocation.

Specially-designedvehicles could rendezvous with old rocket bodies, for instance, and attach apropulsion system or so-called drag augmentation device onto the object. Theresult would quicken the debris' descent to Earth. "That vehicle couldattach that device to an old satellite and then maneuver to another satelliteand attach another device, etc., etc," Johnson said. (The glitch: The vehiclesand operation would be complicated and costly.)

Or, long,thin wires called tetherscould help to bring down objects. The most promising tether concept involvesattaching the tether to a spacecraft prior to launch. (The glitch: Even thoughtethers work on paper, "unfortunately, we haven't had a successfuldemonstration yet," Johnson said.)

To date,most of the remediation research and experimenting has involved only academicinstitutions and national space agencies.

"Thereis not a business base yet for doing this," Johnson said. Though hedoesn't expect truly feasible ideas for remediation, and the associatedbusiness opportunities, in the near-term, "that doesn't mean we're notgoing to keep looking and trying.?

- 10 Most Memorable Pieces of Space Debris

- Orbital Overload: Space Debris Crowds the Not-So-Friendly Skies

- Great Space Quizzes: The Space Shuttle