Life Outside Our Solar System Might Exist on Exomoons

As some scientists search for habitable planets outside our solar system, other researchers are tackling a similar question for the moons of these planets. So-called exomoons have yet to be found outside our solar system, and a detection could be a decade away — or more.

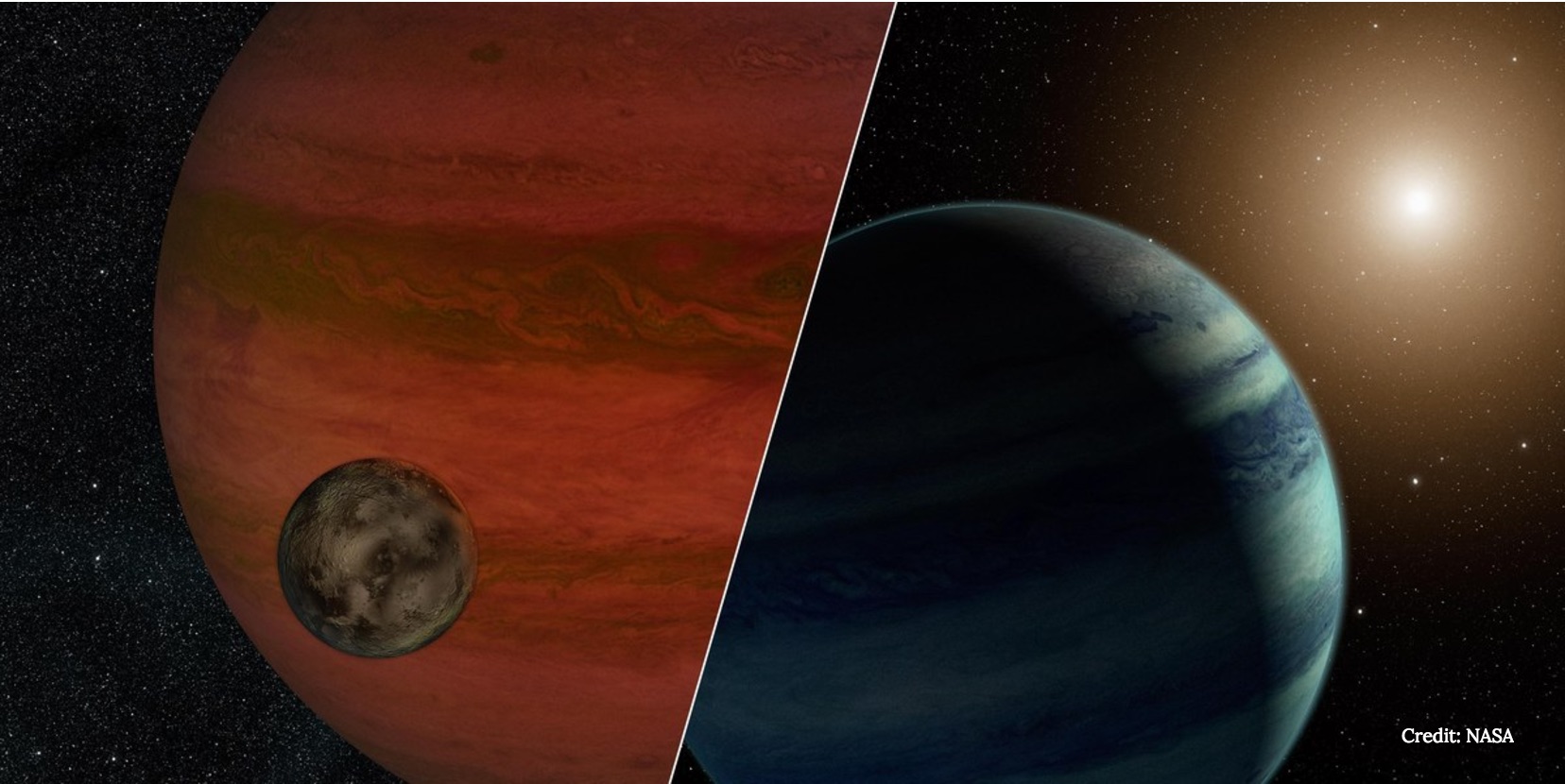

But scientists, writing in a new research paper, theorize a Mars-sized exomoon of a gas giant planet and ask whether or not liquid water could be found on its surface.

In our own solar system, the closest analog is Jupiter's Ganymede, the biggest moon in the solar system and about five-sixth the size of Mars.

As for this theoretical Mars-sized exomoon, the picture is murky. The scientists considered energy sources such as stellar radiation (which changes as a function of distance to the star), the stellar reflected light from a Jupiter-sized planet on the moon, the planet's own thermal emission on the moon, and the tidal heating inside the moon that is generated due to the changing gravitational pull of the planet. (This tidal heating would be most pronounced if the moon had an eccentric orbit, like the volcanic moon Io has around Jupiter.)

RELATED: 'Habitable' Exoplanets Might Not Be Very Earth-Like After All

It's know that tidal heating rates decrease if a moon is molten inside, because lava creates an inherent negative feedback mechanism where the heating sort of switches off, and the moon cools down inside. This is called the "tidal thermostat effect," co-author of the paper Rene Heller said in an email. Heller is an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany.

"We investigate, for the first time, the interplay of all the possible exomoon heat sources as a function of various distances from the host star," he added. "Actually, we even consider two possible types of host stars: a sun-like star, and a red dwarf star (an M dwarf)."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For a sun-like star, the authors found that any moon around a gas giant beyond three astronomical units, or three Earth-sun distances, would have a high enough energy flux to stop the tidal thermostat effect from happening. But if the moon is volatile enough, it could have global volcanism — just like what we see on Io.

Heller described this situation as "dangerous" for organisms.

"They might have lots of liquid surface water, but their surfaces could at the same time be blotched with devastating volcanoes," he wrote. "Nevertheless, we illustrate that they could be habitable given the right amount of tidal heating, and we show at which distances to their planets these moons would need to be."

M-dwarfs are a common target for exoplanet searches because they are smaller and dimmer, making it easier to see planets passing across their surfaces, or the effect of planets tugging on the star itself. But for exomoons, it's even less clear how habitable they would be in such a system. "Moons cannot be stable in the very inner regions of the stellar habitable zone," Heller said.

The best examples for tidally heated bodies in our own solar system are all moons: Jupiter's Io and Europa, as well as Saturn's Enceladus. While Europa and Enceladus are strongly suspected to have oceans underneath an icy surface, Heller pointed out his research is more focused on habitability on the surface of the moon. A better analog, he said, might be Saturn's moon Titan — but with a much warmer surface. Titan has a thick orange atmosphere, as well as liquid hydrocarbon lakes.

"Due to observational selection effects, which will prefer big moons around low-mass planets, I think the first exomoon will be unlike anything we know from the solar system," Heller said.

RELATED: What Cassini's Daring Ring-Dive Around Saturn Could Tell Us About Uranus

"It could be a Mars-like thing around an Earth-like planet, or an Earth around a Neptune, at a distance to their star that could be similar to Mercury's distance from the Sun (sufficiently close so that we have enough transits to find it). It'll probably be something that will be incredible at first glance, like a planet around a pulsar or a hot Jupiter. I'm really curious to know what this object will be like."

While there are several new planet-hunting telescopes joining astronomy in the next decade, Heller said they are not optimized for exomoons. Searching for exomoons is financially risky and the payoff highly uncertain, which means it is likely to remain a low priority for the astronomical community.

The James Webb Space Telescope, a multi-purpose telescope which launches in 2018, is expected to look at only a few exoplanets — so its chances of finding an exomoon are low, Heller said. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which also launches next year, will only observe very short-period transiting planets. "These planets will be so close to their stars that any moon around the planet would be immediately flung out of the system by the stellar gravitational perturbations," Heller said.

Better other chances could come with the European Extremely Large Telescope, which is currently under construction, or CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite), another European space telescope.

"I know that some people in the CHEOPS Science Team are actively compiling strategies to go and search for moons around transiting planets in wider orbits," Heller said. But he added the "ultimate weapon" would likely be PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars), which will launch around 2024. It will conduct dedicated planet searches like the Kepler space telescope, but around more bright stars.

WATCH: We Found New Planets. No, You Can't Live There

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.