Newfound Moon Craters Point to Asteroid Puzzle

Newfound lunar craters suggest that asteroids that smashed into the moon long ago were very different from the ones that now occupy the asteroid belt, researchers say.

Solving this asteroid mystery could yield answers regarding the habitability of the early Earth, scientists added.

Scientists think swarms of asteroids and comets pummeled Earth, the moon and the other worlds of the inner solar system during an era known as the Late Heavy Bombardment about 4.1 billion to 3.8 billion years ago. The many giant, round craters known as lunar basins that pockmark the moon's surface now stand as mute testimony to this violent time. [The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

Although many lunar basins are readily apparent to the naked eye, their exact number, sizes and origins remain unclear. Lunar basins are difficult to study because their details are often concealed by the destructive effects of subsequent impacts and volcanic eruptions.

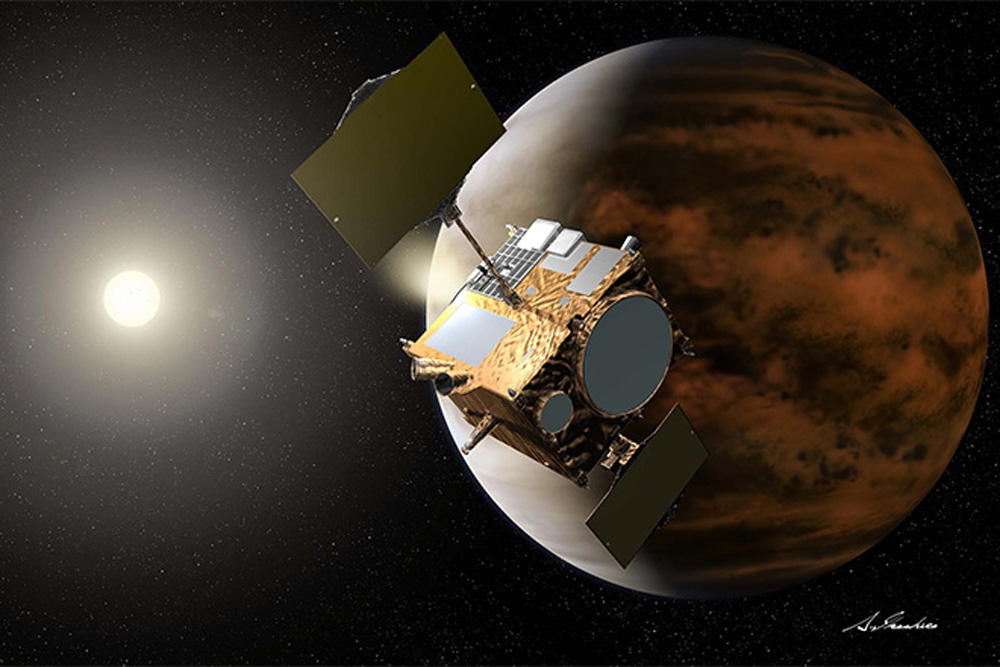

To learn more about impact basins on the moon, scientists relied on gravity datagathered by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission, which consisted of two spacecraft named Ebb and Flowthat were in the same orbit around the moon. Tiny changes in the distance between the GRAIL probes caused by the gravitational pull of clusters of rock have allowed researchers to probe the moon's structure and composition in unprecedented detail.

The researchers scanned the GRAIL data for craters 100 miles (160 kilometers) or more wide. They concentrated on basins with craters shaped like concentric rings, a kind of structure unique to impact basins.

The scientists not only confirmed 27 concentric-ring impact basins, they also identified 24 more structures that might be such craters, including three new to science. These newly identified craters — named Asperitatis, Bartels-Voskresenskiy, and Copernicus-H — are located on the lunar near side, and substantially increase the known number of large impacts on the moon.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers also confirmed that larger impact basins are preferentially found on the moon's near side, which always faces Earth, whereas the far side features smaller basins. Previous research suggests this is because the lunar near side was warm during the early formation of the moon, creating an ideal environment for big craters to form, said study lead author Gregory Neumann, a planetary geophysicist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The new findings support previous research suggesting that the asteroids that pummeled the moon long ago differed in surprising ways from the rocks now seen in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Neumann said.

If ancient asteroids occupied the same size range as modern asteroids, there are more intermediate-size lunar impact basins than one would expect, and half as many giant impacts "that would obliterate almost half the moon," Neumann told Space.com. "In other words, a deficit in the number of objects capable of producing megabasins that would destroy all forms of life."

More research is needed to understand the nature of asteroid impacts in the early solar system, which has implications for understanding "the habitability of the early Earth," Neumann said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Oct. 30 in the journal Science Advances.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us