Giant Galaxies May Be Better Cradles for Habitable Planets

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

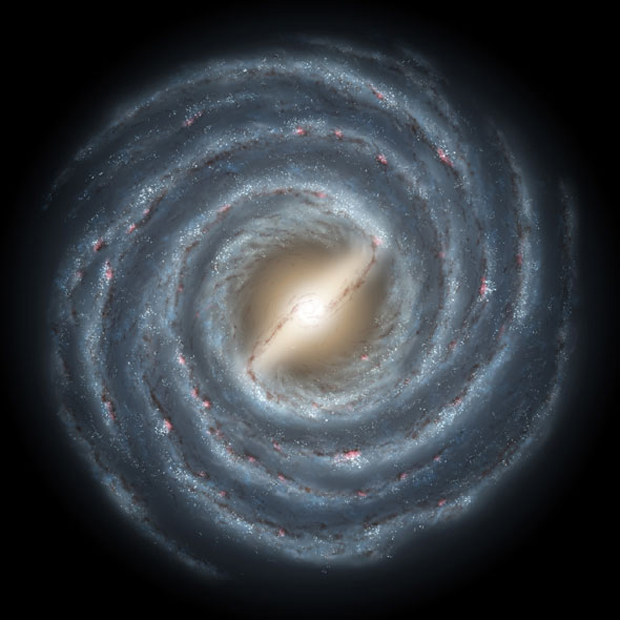

Galaxies like the Milky Way may not be the best cradles of life in the universe — giant galaxies devoid of newborn stars and at least twice as massive as the Milky Way could host 10,000 times more habitable planets, researchers say.

In the past 20 years, astronomers have confirmed the existence of nearly 1,900 planets that orbit stars other than our sun. These findings have led researchers to speculate which moons, planets and stars might be the best at supporting recognizable forms of life. Scientists have even investigated whether there might be a galactic habitable zone in the Milky Way — a region of the galaxy favorable to the formation and evolution of habitable worlds.

Now, researchers have analyzed more than 140,000 neighboring galaxies to answer the question, "Which type of galaxy might be the most habitable in terms of complex life in the cosmos?" [10 Alien Planets That Might Be Habitable]

One potentially surprising conclusion? The number of habitable planets is not the largest in spiral galaxies like ours, study co-author Anupam Mazumdar, a particle cosmologist at Lancaster University in England, told Space.com.

The researchers suggested three criteria that might be important in determining a galaxy's habitability. The first was the total mass of their stars, representing potential homes to planets. The next was the amount of mass in "metals" they had — elements heavier than hydrogen and helium — since this kind of matter is needed to build worlds as well as life as it is known on Earth. The last was their ongoing rate of star formation, since galaxies with high star-formation rateswould pack stars closer together, increasing the chance that any stars with habitable worlds might dwell near massive stars that will eventually die in supernovas that can trigger mass extinctions.

"This is the first computation ever where we are discussing life in cosmological scales, and not within our own galaxy," Mazumdar said. "It is fair to say that our paper is the first 'cosmobiology' paper, which has perhaps opened a new avenue to understand habitability in the cosmos."

The scientists investigated galaxies that astronomers have observed using the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. About 1,800 of these 140,000 galaxies are comparable to the Milky Way in terms of total mass in stars and ongoing star-formation rates, Mazumdar said. (The Milky Wayweighs as much as about 60 billion suns, and gives birth to about three suns per year, the researchers noted.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

They found that the most habitable kind of galaxy was the metal-rich type at least twice as massive as the Milky Way with less than a tenth of its star-formation rate. In fact, the researchers said this type of galaxy can host 10,000 times as many Earth-like planets as the Milky Way. Such galaxies could also host 1 million times more gas giants, which can, in turn, host potentially habitable moons, the researchers added.

"The most important implication of our analysis is that our cosmos is actually full of life," Mazumdar said.

However, don't expect astronauts to visit such galaxies anytime soon. The nearest such galaxy is Maffei 1, discovered in 1968, which lies more than 9.5 million light-years from Earth.

About 200 ofthe 140,000 galaxies analyzed were the potentially life-rich kind the scientists defined. Such galaxies are relatively shapeless. "Perhaps they are not eye-catching, looking at their pictures, but they are key to understanding extragalactic life in our universe," Mazumdar said.

In the future, computer simulations of these galaxies could investigate where their habitable planets are located, Mazumdar said. He and his colleagues detailed their findings in a paper accepted for publication in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us