How to See Elusive Planet Mercury in the Morning Sky

This month the evening skies are ablaze with planets: Venus, Mars, and Saturn are all shining brightly. Jupiter is also present, but dropping rapidly behind the sun.

This concentration of planets in the evening sky leaves little to see in the morning sky. But wait—here comes Mercury.

Although Mercury is almost as bright as the other naked-eye planets, it is an elusive target for skywatchers. This is because it never strays very far from the apron strings of the sun. Most people have never seen Mercury.

This April is a good opportunity to catch a glimpse of Mercury as it rises in the east just above the sun. This will be a better opportunity for observers in the Southern Hemisphere, though northerners also will get a chance around mid-month.

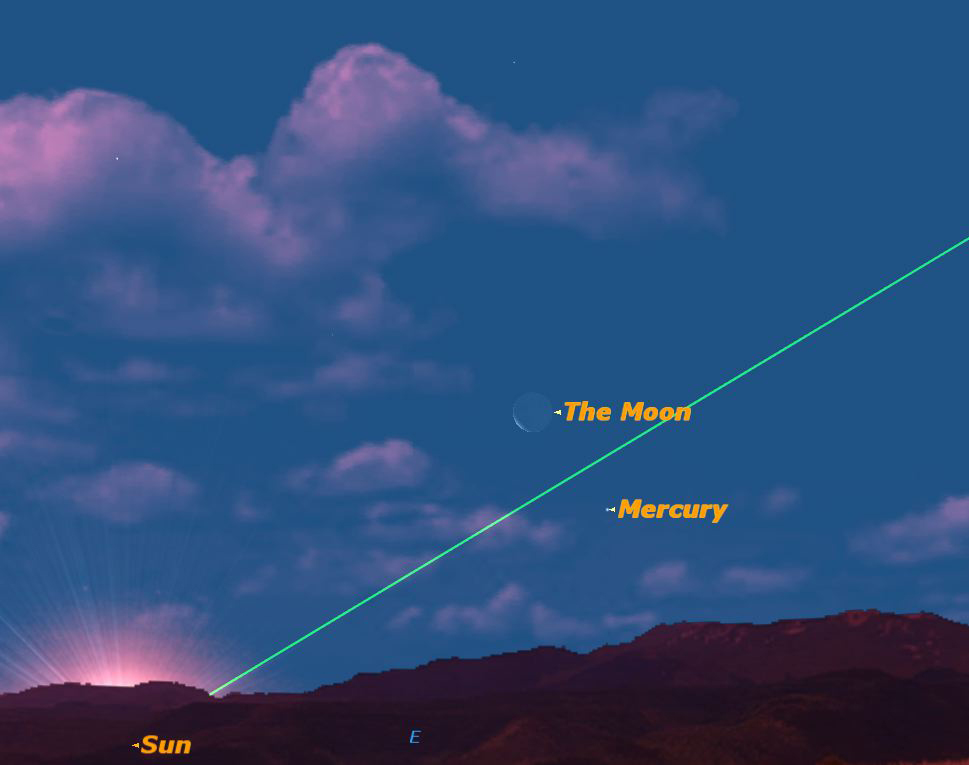

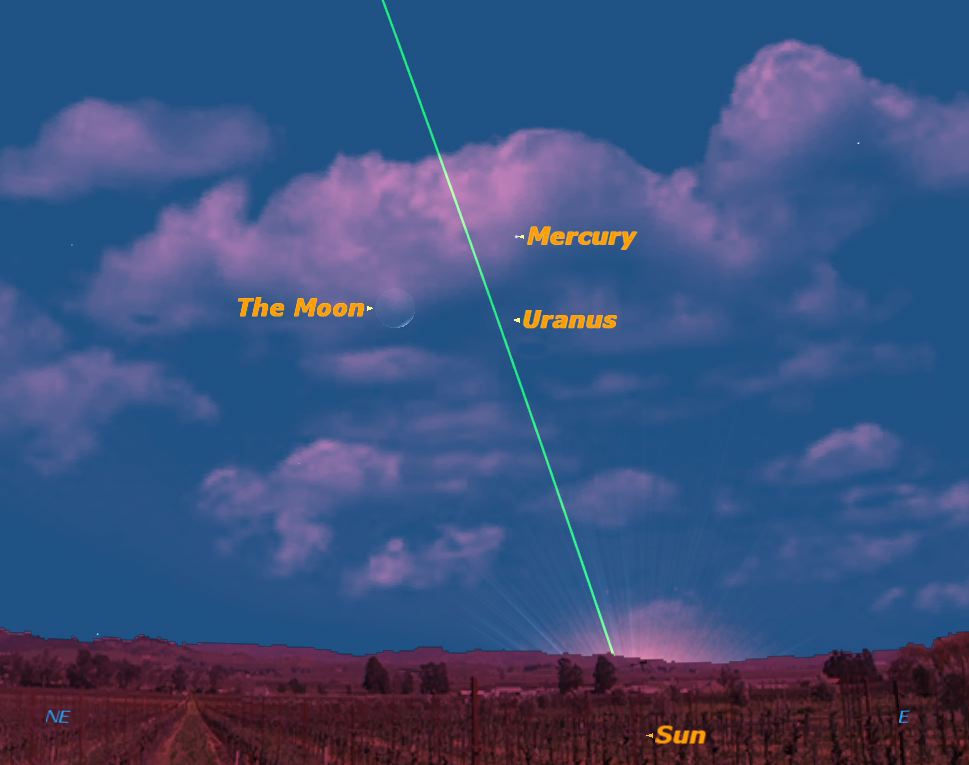

The two sky maps of Mercury accompanying this skywatching guide show where to look to see Mercury in the eastern sky at dawn.

The first sky map shows the view from Melbourne, Australia, on the morning of April 19. This is an auspicious day to observe Mercury because it will be at its greatest distance from the sun, placing it highest in the sky, and it will be close to a slender waning crescent moon. [Latest Mercury photos from NASA]

Mercury will still be well placed on this date as seen from the Northern Hemisphere (in the second map), but will be much lower in the sky, and harder to see if you look much earlier or later in the month.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These differences between north and south are caused by the angle which the ecliptic makes with the horizon. The ecliptic is the path across the sky taken by the sun, moon, and planets.

In March and April at dawn the ecliptic is almost vertical in the Southern Hemisphere, but almost parallel to the horizon in the Northern Hemisphere. These angles are reversed in evening twilight, which is why Venus and Jupiter are putting on such a fine show in the northern hemisphere evening twilight.

The situation is reversed in September and October, with the ecliptic being vertical in the northern dawn and horizontal in the southern dawn. For most of the planets this makes little difference, but it affects Mercury strongly because of its proximity to the sun, and makes for strikingly different apparitions at different times of the year in northern and southern hemispheres.

So, southerners, enjoy nearly a month of fine views of Mercury; northerners rise to the challenge of spotting it briefly at mid-month.

Mercury is best observed with binoculars because its tiny speck of light is often hard to spot with the naked eye. When viewed in a telescope, it is a tiny almost featureless "half moon."

Note that Uranus is also close to Mercury at mid-month, though it is too faint to be seen in the morning's twilight sky.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.