Water Shield May Have Seeded Earth’s Oceans

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The early solar system was tough on molecules. There werefew places then to hide from the harsh ultraviolet radiation from the young Sun.However, new theoretical models show that water vapor provided a kind of shield? like the ozone layer in Earth's atmosphere ? that protected molecules insidethe planet-forming disk.

This water shield may have helped the disk hold onto waterthat later seeded the Earth'soceans. It could have also provided a safe haven for some of the biologicalbuilding blocks known to form in space. ?

"Water is basically capable of sacrificing itself toprotect the chemistry below it," says Ted Bergin of the University ofMichigan in Ann Arbor.

Bergin and colleague Thomas Bethell calculated the survivalrate of water vapor in the inner regions of young planetary systems. Somewhatunexpectedly, they found that several thousand oceans-worth of water can escapeUVdestruction.

The results, reported in a recent issue of the journal Science,may explain recent observations of water vapor around young stars, as well as helpscientists trying to model how planets form.

Star light, star bright

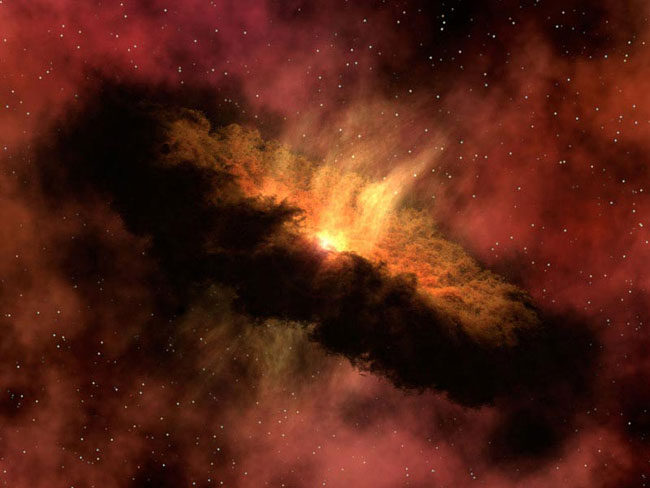

When a star is born out of a dense cloud of dust and gas,some of the cloud material ends up in a flat disk circling the central star.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Initially, the gas in the cloud contains some simplemolecules, but once the star "turns on" these molecules are at riskfrom the stellarradiation.?

"Molecules are fragile," Bergin says. "Theultraviolet light can easily break them apart."

Ultraviolet photons striking the molecule H2O, for example, willstrip off one hydrogen and then the other, leaving a single oxygen atom.

Water and other molecules are provided some protection by dustin the disk. But as the grains grow bigger on their way to forming planets,they no longer block UV radiation.

The general consensus was that there should be a limitednumber of molecules around million-year-old stars when grains have grown, andyet recentobservations have detected large quantities of water and OH vapor floatingin the inner disk regions of several such stars.

To explain these observations, some scientists suggestedthat comets from cold outer regions fly in towards their host star, releasing frozenwater through evaporation. However, this hypothesis doesn't seem to account forthe OH data in the disk, Bergin says.

Sun screen for the solar system

Bergin had a hunch that the water vapor in the inner disk wasdense enough that it could chemically reassemble itself just as fast as the UVwas destroying it. He and Bethell ran models for various star luminosities anddisk temperatures and found that in most cases a thin layer of water surroundingthe disk could absorb the incoming radiation.

"What Bethell and Bergin have showed is that if wateris present, it can protect itself from destruction as the water begins toreform on quick timescales, preventing the light from destroying all ofit," says Fred Ciesla of the University of Chicago.

The authors predict that the amount of "spacemist" surrounding a young star should be equivalent to many thousands ofoceans. They show that this is consistent with three previous water detectionsin planet-forming disks.

The water shield not only protects other water molecules,but it also would keep radiation from destroying other molecules in the innerdisk region.

"Water in the disk provides this nice umbrella," Berginsays.

Under this umbrella, organic chemistry could operate,perhaps leading to some of the biological building blocks that have beendetected in veryold meteorites and the innermost regions near young stars.

Follow the water

One nagging question is what happens to all the oceans of waterin the inner disk as the star gets older and its planets grow up.

Bergin believes the water vapor within about 1 AU (the Earth-Sundistance) eventually gets destroyed. "Over time, radiation will win,"he says.

But out at 3 AU (where our solar system's asteroid belt islocated) the lower temperature may have allowed water vapor to condense onto thesolid material forming in the disk. As it so happens, astronomers have recentlydetected icy asteroids that have comet-like compositions but appear tooriginate from inside the asteroid belt.

There has been some speculation that icy asteroids may havedelivered water to the early Earth. The idea stems from the fact that ourplanet's oceans have a high ratio of deuterium to hydrogen, signifying that thewater formed in a colder part of space than where Earth formed.

This could mean that some of the water vapor from the earlydays of our inner solar system wound up in our drinking supply.

Ciesla is somewhat skeptical. He thinks the situation thatthe authors are considering occurred too late in the evolution of the solarsystem to explain Earth's water. By the time the water-shielding mechanism becomesimportant, the solid material would have developed into clumps of rock, resultingin less overall surface area onto which water could condense.

However, Ciesla does believe these new results will helpscientists peel away some of the uncertainty about the planet formationsupposedly going on inside the thick dusty disks around young stars. ?

- Video Show? Attack of the Sun

- AreWe Drinking Comet Water?

- HowEarth Survived Its Birth

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.