Deep Impact Overview: By The Numbers

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

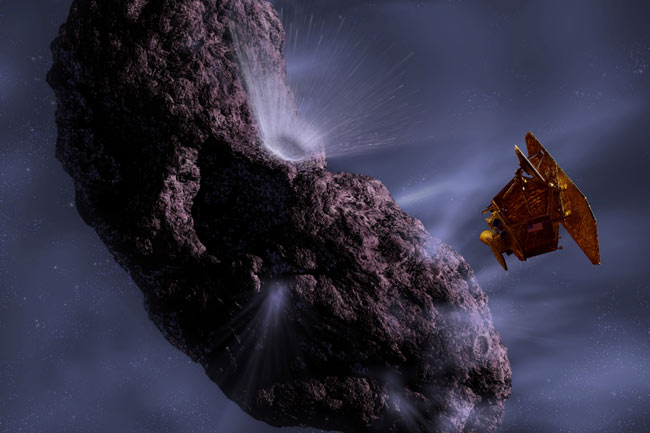

It's a match six years in the making and the underdog doesn't stand a chance, but that hasn't dampened the excitement of NASA's Deep Impact scientists one bit.

This July 4th, the agency's Impactor spacecraft--an 820-pound copper probe shaped like your typical living room coffee table--will go up against the comet Tempel 1, a massive hunk of rock and ice about the size of Washington D.C.

SPACE.com looks at the step-by-step sequence of events leading up to this face-off and the technology involved in trying to hit a speeding object 83 million miles from home.

The Deep Impact spacecrafts--Flyby and Impactor--were launched together aboard a Delta II rocket from Kennedy Space Flight Center on January 12. For the past six months, the pair have been making their way steadily towards the comet, relying on little more than Newtonian mechanics and a few well-aimed trajectory corrections to keep them on course. They will continue to cruise along like this until approximately 24 hours before impact, when they will separate and the real show begins.

FLYBY:

About the size of a Volkswagen Beetle automobile, Flyby is the larger of the two Deep Impact spacecrafts and will carry two of the mission's three primary research instruments.

The High Resolution Instrument (HRI) is the crown jewel of the three and is the largest telescope ever to be deployed into deep space. In addition to the telescope--which has a nearly 12-inch aperture and a maximum predicted resolution of about 6 feet--the HRI also contains an infrared spectrometer and a multi-spectral digital camera. Earlier difficulties with the device regarding its ability to focus properly--it was sending back blurry images--have been corrected.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Unlike the HRI, the Medium Resolution Instrument (MRI) will be able to take wide-angle shots of the entire comet. It has a maximum resolution of about 30 feet and will serve as HRI's backup. The MRI's wide field of view will be crucial for guiding Flyby spacecraft safely towards Tempel 1, especially during the last few days of the approach.

IMPACTOR:

The final research instrument, the Impactor Targeting Sensor (ITS), is located on the Impactor spacecraft. The ITS is nearly identical to Flyby's MRI and will be used to guide Impactor to Tempel 1 during the final approach. It will also take pictures of the comet until the moment of impact.

Impactor's task is a difficult one. From a distance of more than half a million miles, it must aim for a sunny, well-lit spot on Tempel 1 that is less than 4 miles in diameter, all while zipping along at 23,000 miles per hour itself.

Because the impact will take place so far from earth, it is crucial that Impactor be able to guide itself towards Tempel 1 autonomously and adjust its course automatically if the need arises. To help it do this, Impactor uses special Autonav targeting software specially designed for the mission by Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). JPL is managing the mission for NASA.

24 HOUR COUNTDOWN:

Twenty-four hours before collision, Impactor will separate from Flyby and each spacecraft will perform their separate duties:

- How to Watch July 4 Comet Impact

- The History of Tempel 1, the 'Deep Impact' Target

- Deep Impact: Probing A Comet's Inner Secrets

- Deep Impact on Target Despite Blurry Vision

- Deep Impact Special Report

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.