Massive Black Hole Bends Light to Magnify Distant Galaxy

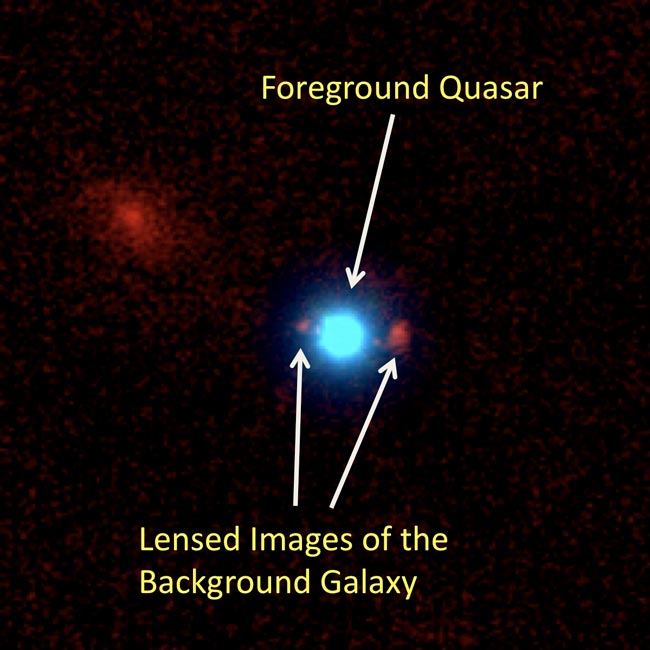

A giant black hole spouting energy from inside a galaxy isacting like a cosmic magnifying glass, giving astronomers a clear view of an evenmore distant galaxy behind it.

It is the first time a quasar ? the central region of agalaxy dominated by an energy-spewingblack hole ? has been discovered acting as a gravitationallens. The cosmic lens phenomenon was first predicted by Albert Einstein's theoryof general relativity.

The discovery gives astronomers a glimpse at two galaxies atonce, allowing researchers to photograph the distant object while weighing andmeasuring the intervening galaxy and the bright powerhouse at its core.

The quasar is known as SDSS J0013+1523 and located about 1.6billion light-years from Earth.

Warped space-time

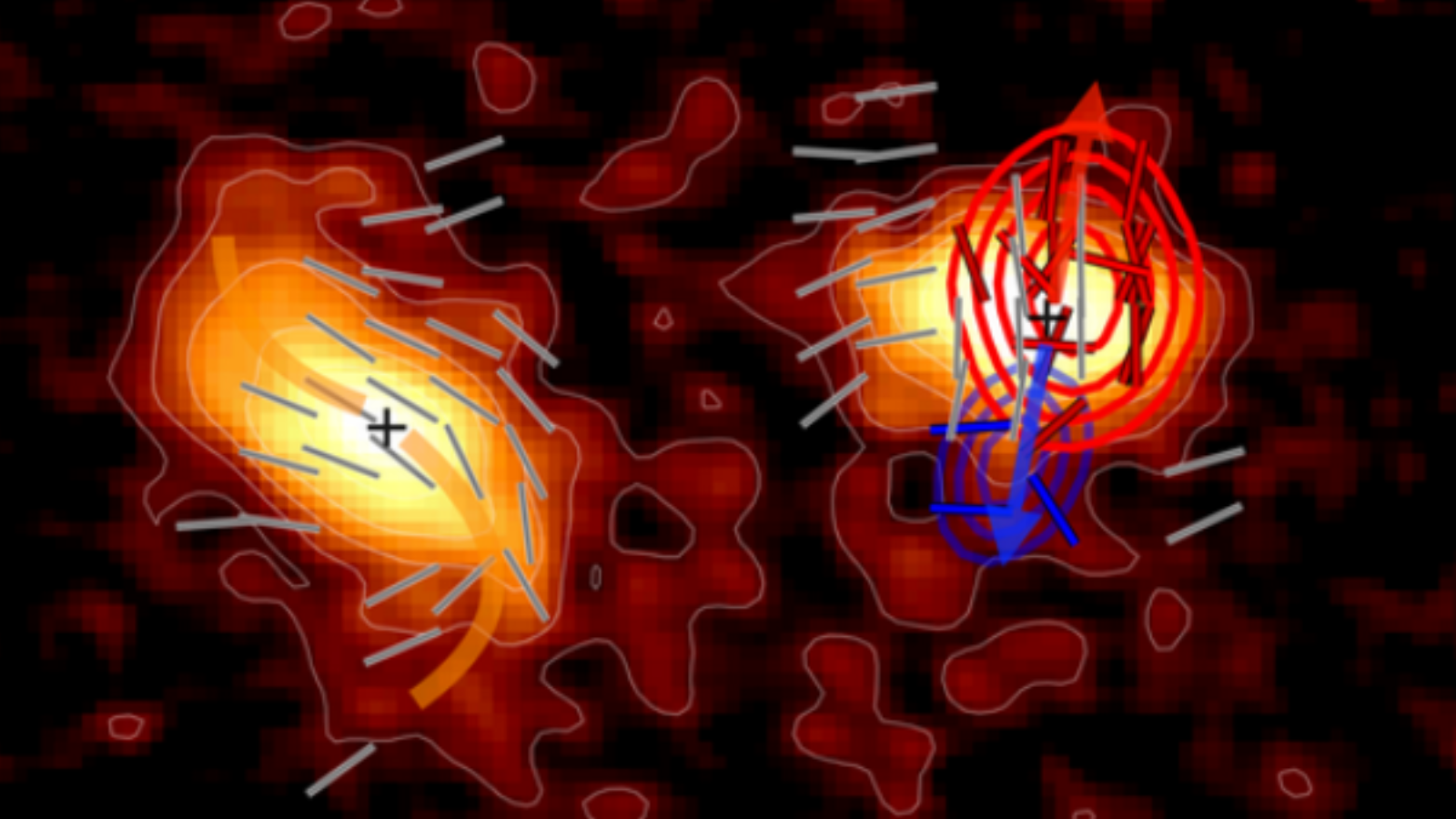

According to the theory, very large masses warp thespace-time around them, even causing light to bend as it travels through theregion. Thus, light from farawayobjects sometimes can be magnified by the bent space-time to provide alarger and brighter ? though also distorted and curved ? view.

In this case, scientists are more interested in studying thelens itself than the magnified image.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Galaxies that host quasars are hard to study because theirlight is often overpowered by the blaring radiation from material falling ontothe supermassiveblack holes in their centers. A single quasar can be 1,000 times brighterthan an entire galaxy of 100 billion stars.

"It is a bit like staring into bright car headlightsand trying to discern the color of their rims," lead researcher Fr?d?ricCourbin of the Ecole Polytechnique F?d?rale de Lausanne in Switzerland said ina statement. By studying the way a quasar magnifies light as a gravitationallens, he said, "we now can measure the masses of these quasar hostgalaxies and overcome this difficulty."

Weighing quasars

The newfound lens, and similar ones being sought by researchers,could provide an opportunity to learn about the galaxies that shelter quasarsin their centers.

By studying the way the quasar magnifies the distant light ?including the shape of its distortion and the number of magnified images thelens produces ? scientists can measure how matter is distributed in the lensgalaxy. They can even calculate the total matter of the quasar and its hostgalaxy.

Often quasarsare discovered when their light is being magnified by an intervening galaxyacting as a gravitational lens. Scientists set out to look for a case of thisreverse lensing of a galaxy's light by a quasar by looking through the dataobtained by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey ? a detailed map of a quarter of thesky.

It was through that study that researchers found the quasar SDSSJ0013+1523 acting as a cosmic lens.

"We were delighted to see that this idea actuallyworks," said Georges Meylan, a professor of physics at Ecole PolytechniqueF?d?rale de Lausanne."This discovery demonstrates the continued utility ofgravitational lensing as an astrophysical tool."

The researchers published their findings July 20 in thejournal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

- How Black Holes Gobble Dark Matter

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Video: Black Holes: Warping Time & Space

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.