Biggest Space Explosion Creates Giant Bubbles

The largest explosion ever seen in space reveals black holes to be more influential than expected, perhaps sometimes stifling star formation in a galaxy while gobbling up trillions upon trillions of tons of gas.

The eruption has been ongoing for some 100 million years, astronomers said Wednesday.

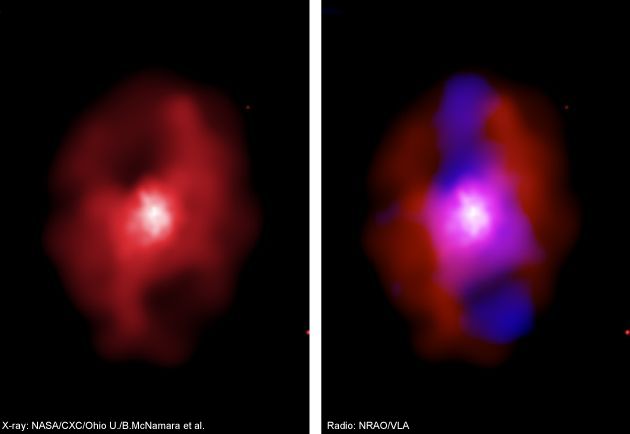

The outburst is orchestrated by a supermassive black hole that anchors a distant galaxy sitting amid a tight cluster of galaxies. The black hole has blown two huge bubbles into the galaxy, shoving aside a colossal amount of gas equal to the mass of a trillion Suns, or more than all the stars of our own Milky Way Galaxy.

Each bubble is many times bigger than those seen in previous studies.

Here's what happens: While the black hole feasts, a lot of incoming gas is ejected violently back into the galaxy along the black hole's axis of rotation. Two high-speed jets of superheated gas carve out the ever-expanding bubbles.

The scene was captured by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's Very Large Array.

Rare and puzzling

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The explosive event, on a scale not expected, is the sort of thing that likely occurred frequently early in the history of galaxy construction, at a time when the universe was smaller and more crowded.

The eruption is 2.6 billion light-years away, compared to more than 12 billion light-years for the most distant known galaxies. A light-year -- the distance light travels in one year -- is a measure of time, too, so the galaxy is more modern than many, seen as it existed well after the bulk of galaxy formation had taken place throughout the cosmos.

By relying on a standard assumption that 10 percent of the gravitational energy of the whole setup goes into launching the jets, the scientists calculated how much gas was swallowed during the 100-million-year eruption. They are surprised that there was enough gas available to this relatively modern black hole to fuel such an outburst.

"I was stunned to find that a mass of about 300 million Suns was swallowed," said lead researcher Brian McNamara of Ohio University. "This is almost as massive as the supermassive black hole that swallowed it."

Other studies suggest supermassive black holes have not grown so significantly or rapidly in the recent past.

"The interesting issue is, what is the source of the fuel in this case?" said Paul Nulsen of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center of Astrophysics.

He has some ideas.

"It might come from a merging galaxy, either gas and stars, or even another black hole falling into an existing black hole," Nulsen told SPACE.com. "It might also be a large amount of the hot X-ray emitting gas that cooled to low temperature. Either way, it would represent the tail end of galaxy formation."

The explosion is not likely the biggest in the universe, but it is the biggest so far measured. Any larger explosions are probably further back in time, thus farther away and harder to detect and study.

"But it is unlikely that they were much bigger than this one, even in the very distant past," McNamara said.

Size and power

The sizes of the two cavities indicate the power of the eruption, Nulsen said. They are each about 650,000 light-years across. A light-year is about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers).

A shock wave something like a sonic boom surrounds both of the bubbles. It forms because the cavities expand so rapidly that the gas has to move very quickly to get out of their way. The properties of the shock helped the researchers determine the energy of the outburst.

The observations could help solve a puzzle over why some galaxies don't form stars at the rate theory predicts. As a galaxy matures and cools down, star formation should increase. The scientists figure expanding space bubbles continually replenish the galaxy and its surrounding cluster with energy.

"We think that the main effect of eruptions like this is to stop stars from forming by preventing hot gas from cooling down," Nulsen said.

The results are detailed in the Jan. 6 issue of the journal Nature.

The astronomers don't yet know if the eruption has been continuous, or whether there have been spurts of activity. They do have an idea of what the future holds.

"The cavities and shock will dissipate, leaving behind very little trace of their existence," Nulsen said.

- The New History of Black Holes

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.