Yin-Yang of Saturn's Odd Moon Explained

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

New data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft at Saturn helpsexplain the bizarre yin-yang appearance of the ringed planet?s odd moonIapetus, where one side is dark and the other is bright.

The images and heat-mapping data collected by Cassini supportthe leading explanation of the moon?s strange appearance, which suggests that migratingice makes halfthe moon reflective and bright, while the other half is dust-covered anddark.

The new findings are described in two papers publishedonline Dec. 10 in the journal Science. TheCassini spacecraft launched in 1997 and has been orbiting around Saturnsince 2004.

Astronomers have been puzzled by the moon's two-tonedexterior for more than 300 years. When the French-Italian astronomer GiovanniDomenico Cassini discovered Iapetus in 1671, he noticed that the surface ismuch darker on its leading side, the side that faces forward in its orbitaround Saturn.

Images from Voyager and the Cassini probe have shown that thedark material on the leading side extends onto the trailing side near theequator. The bright material on the trailing side, which consists mostly ofwater ice and is 10 times brighter than the dark material, extends across thenorth and south poles onto the leading side.

Cassini's Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) cameras tookpictures of Iapetus during the spacecraft?s close flyby of the moon on Sept. 10,2007.

"[Cassini?s] ISS images show that both the bright anddark materials on Iapetus' leading side are redder than similar material on thetrailing side," said Tilmann Denk of the Freie Universitat in Berlin, leadauthor of one of the Science papers.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Denk suggested that the moon's leading side is colored (andslightly darkened) by reddish dust that Iapetus has swept up, perhaps from oneor more of Saturn?s outer moons, in its orbit around Saturn.

The dust may be related to the giantring around Saturn recently discovered by NASA?s Spitzer Space Telescope.However, the ???images show that this infalling dust cannot be the sole causeof the extreme brightness disparity.

?It is impossible that the very complicated and sharp boundary between the darkand the bright regions is formed by simple infall of material," Denk said."Thus, we had to find another mechanism."

?

Close-up images provide a clue, showing evidence for thermal segregation, inwhich water ice has migrated locally from sunward-facing and therefore warmer areas,to nearby pole-facing and therefore colder areas, darkening and warming theformer and brightening and cooling the latter.

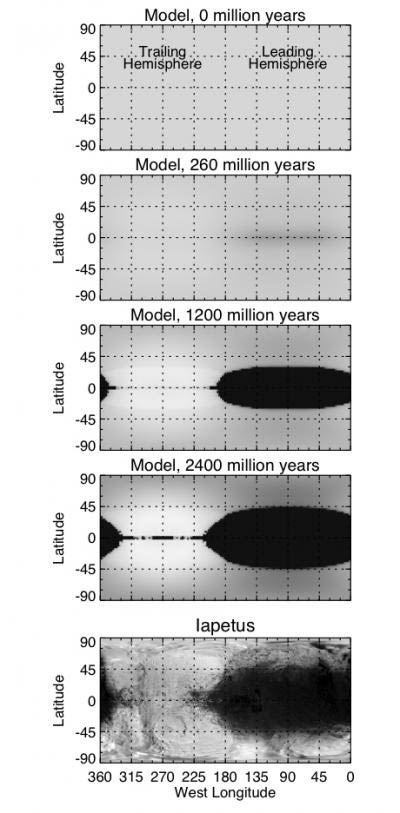

The second Science paper, by John Spencer of Southwest Research Institute in Boulder,Colo., and Denk, suggests that the migration of water ice plays a role. Theresearchers created a computer model of the moon by combining the ISS imagery withthermal observations from Cassini?s Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS).

CIRS observations in 2005 and 2007 found that the darkregions reach temperatures high enough (129 degrees Kelvin, or -227 degreesFahrenheit) to evaporate much of the ice over billions of years. Iapetus? very longrotation period, one day is equal 79 Earth days, contributes to these warmtemperatures by giving the sun more time to warm the surface each day than on faster-rotatingmoons.

Spencer and Denk propose that the infalling dust darkens theleading side of Iapetus, which therefore absorbs more

sunlight and heats up enough to trigger evaporation of the ice near theequator.

That evaporating ice recondenses on the colder, brighter poles and on the moon?strailing hemisphere. The loss of ice leaves dark material behind, causingfurther darkening, warming, and ice evaporation on the leading side and near theequator. Simultaneously, the trailing side and poles continue to brighten andcool due to ice condensation, until

Iapetus ends up with the extreme contrasts in surface brightness seen today.

The relatively small size of Iapetus, which is just 900 miles (1,500 km)across, and its correspondingly low gravity, allow the ice to move easily fromone hemisphere to another.

"Iapetus is the victim of a runaway feedback loop,operating on a global scale," Spencer said.

- Image Gallery: Cassini's Latest Discoveries

- Cassini's Greatest Hits: Images of Saturn

- Video ? Cassini's Mission to Saturn

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.