Dark Energy Search Could Aid Planet Hunters

Dark energy isn't good for life in the universe. Thismysterious substance, which cosmologists believe makes up around 70 percent ofthe universe, may eventually pull apart galaxies, then stars and planets, andfinally atoms and molecules, in what some call the Big Rip.

It?s ironic, then, that the search for dark energy might helpin the search for life in the universe.? That's because planet hunting througha technique called microlensingrequires a similar sort of instrument as a dark energy mission.

"Both dark energy and microlensing planet studies arebest done with a wide-field telescope optimized for infrared observing,"says Peter Garnavich a cosmologist from the University of Notre Dame.

In Europe, the Euclid mission is a proposed space telescopefor characterizing dark energy, but some believe that it might be moreattractive to funding agencies if it included an exoplanet survey. A similarcollaboration is being considered in the United States.

"There is less money for research, so it is importantto have robust, low-risk missions that maximize the scientific return,"says Euclid-team-member Jean-Philippe Beaulieu of the Institut d'Astrophysiquede Paris (IAP).

Converging technology

The first evidence of darkenergy came from supernova observations made a decade ago. The data showedthat the farthest supernovae were fainter than expected, which meant that theexpansion of the universe is accelerating. No known force can do that, so itwas theorized that some unknown energy must be pulling everything apart.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

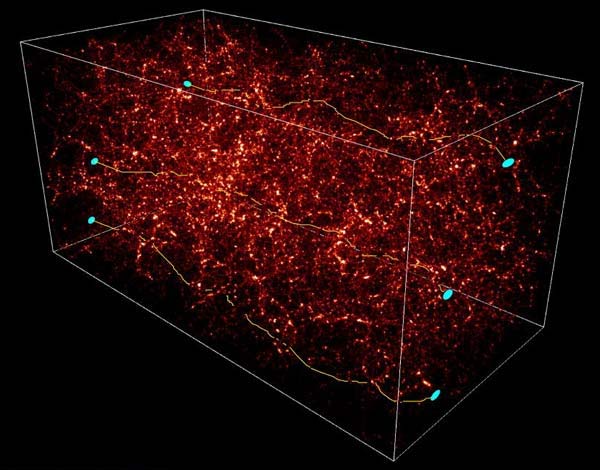

To get a better understanding of dark energy, cosmologistswant to measure how the acceleration has changed over time. This could be donein one of three ways: (1) with more supernova observations, (2) by mapping outthe way galaxies cluster together, or (3) by observing the apparent distortionin the shapes of distant galaxies caused by matter along the line of sight.

All of these techniques require a large space telescope thatcan stare at a big piece of the sky, but this fits the bill of anotherastronomical enterprise.

"The microlensing planet search will also need a largedetector and big sky footprint, so it is natural to think that these twoseemingly different programs could work with the same space telescope,"Garnavich says.

Originally, the marriage of planet hunting and dark energywas part of the DUNE mission that was proposed to the European Space Agency(ESA) as part of its Cosmic Vision 2007.

However, ESA decided that DUNE should be merged with anotherdark energy project called SPACE. The resulting mission, Euclid, is still underreview.

The Euclid design is still being hammered out, but the maininstrument is a 1.2-meter diameter telescope for high-resolution opticalimaging. It would map the distribution of galaxies across the sky, as well as measurethe amount of distortion (so-called weak lensing) caused by the bending oflight as it travels through regions of dense matter on its way to us.

Without any design changes, this dark-energy telescope couldalso search for microlensing events, which are caused by a similar light-bendingeffect involving stars and planets rather than galaxies.

Massive lenses

A microlensing survey detects planets by looking at a largenumber of target stars and waiting for another star to pass near the line ofsight. The mass of the foreground star will bend light around it, causing thebackground star to suddenly brighten. The increase in flux can be anywhere froma factor of a few to a factor of a thousand.

If there is a planet around the foreground star, it mayinvoke an additional blip in the observed light. In the typical microlensingevent, the planet causes the background star to brighten (or sometimes darken) by20 to 30 percent, Beaulieu says.

The data from a microlensing event tells astronomers themass of the star and planet and the orbital separation between them, and also thedistance to the system. But because microlensing systems are typically very faraway, there is little chance to learn more. A microlensing planet is onlyobserved once.

Despite this limitation, important statistical informationcan be collected, says Beaulieu. Microlensing is more sensitive to planets at orbitalradii larger than an astronomical unit, or AU, which is the Earth-Sunseparation.

That means microlensing searches complement other planet-huntingtechniques, like radial velocity and transiting, that are more sensitive toplanets that orbit very close to their star.

"We are arriving at one AU from both ends,"Beaulieu says. "Transiting searcheslike Kepler are moving out from the hot part. Microlensing surveys arecoming in from the cold part."

Filling in the cold part of the planet census ? beyond the"snow line" where surface water is frozen rather than liquid ? isimportant in modeling how planetary systems form.

"Without any understanding of low-mass planets in moredistant orbits, it will be difficult to understand how the different regions ofthe proto-planetary disk interact during the planet formation process." saysDavid Bennett from the University of Notre Dame.? Bennett is the principalinvestigator of the Microlensing Planet Finder (MPF), a dedicatedplanet-hunting spacecraft that NASA is considering.

Aiming higher

There are a number of ground-based telescopes that arewatching the skies for microlensing events. So far they have netted 9 planets,with 6 or 7 more candidates for which the data has not yet been published,Beaulieu says.

Moving a telescope from the ground into space will increaseangular resolution and allow more small stars to be observed. Since there'sonly about a one-in-a-million chance that a background star will be microlensed,observing more stars means better odds of finding planets, especially thosethat are Earth-like.

Beaulieu and his colleagues have determined that ? with 3months of observations from Euclid ? they could survey 200 million stars andpossibly detect 10 Earth-like planets.

ESA is currently reviewing Euclid and 5 other similar-sizedmissions, in order to select which 2 will be selected for launch in the comingdecade as part of CosmicVision 2015-2025.

"I think that a microlensing planet search wouldsignificantly improve Euclid's chances of being funded," says Bennett,whose MPF project might also be coupled to a dark energy mission.

The main drawback of these joint ventures is thatplanet-hunters and cosmologists would have to share observing time, which wouldalso mean sharing financial support.

"Space agencies often divide up their funding intoareas based on broad topics like cosmology or solar system," Garnavichsays. "When a project comes along that can produce good science acrossthese divisions, often the territorial imperative kicks in and the bureaucratsare unwilling to share funding or work with another group even in their ownorganization."

- Gravity's Telescope

- New Planet, Magnified

- Video: Hunting Alien Earths: Kepler Stares At Stars

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.