Strange Asteroid Shapes Explained

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

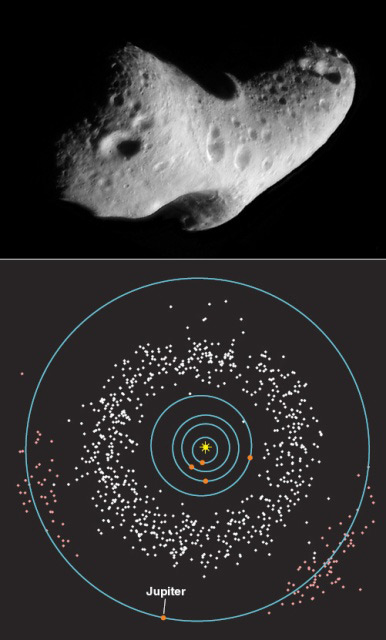

Theasteroids that pepper our solar system come in all shapes, sizes and ages. Whatcauses such a variety among space rocks has been something of a mystery, untilnow.

Researchershave been using a vast database to study a staggering 11,735 asteroids. Theyhave discovered that asteroids change shape over time, and they think they knowthe reason why.

Gyula Szab? from the University of Szeged [Hungary] is the lead author of the study, which was published in the July edition of Icarus.He explains, "There are several hundred thousand asteroidsin our solar system. They orbit the sun, but because they are small theirsurface gravity is low. This means that many have strange, irregular shapes."

Article continues belowScientistslike Gyula think that about one third of known asteroids belong to groupscalled "families." These clusters probably formed from piles ofdebris after largerobjects collided.

Resolved to save time

Determining the shapes of these asteroids presented difficulties for Gyula and his colleague Laszlo Kiss from the University of Sydney. The most accurate data about asteroids comes from spacecraft fly-bys, but only a few asteroids have been examined that way. Radar observations can only be made of objects that get close to the Earth. Telescopes produce detailed images, but only for the largest asteroids.

Anotheroption for obtaining information about asteroids is called "time-resolvedphotometry." The technique is surprisingly simple: By observing asteroidsas they spin in space and then studying the amount of light reflected,scientists can get an idea of their shape. Getting accurate results from thismethod can take a long time, but the researchers realised that digital skysurveys could speed up the process. Such projects study thousands of objectsevery night. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey, for instance, mainly looks at starsand galaxies, but it also has gathered data on asteroids.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Thisprocedure was very economical," says Gyula. "Using photometry,astronomers have determined shapes for about 1,200 asteroids in the past 30 to40 years. We derived the shapes for ten times more asteroids, but in half anhour!"

Surprising results

"Theresults were really surprising," says Gyula. "We saw there werefamilies that included many elongated asteroids, and there were other oneswhich consisted of mostly spheroidal bodies."

Inyoung groups of asteroids there are a great variety of shapes, hinting thatthey formed relatively recently from fragments of rock that later boundtogether. Asteroids in older families tend to be rounder. It seems to take onebillion to two billion years for irregular asteroids to be transformed intosmooth balls.

Butwhat changes the asteroids' shape? Gyula and his team have shown that asteroidschange shape from elongated to roughly spherical due to being impacted duringtheir lifetimes. They are like pebbles on the beach that become worn smoothover many years -- only in space, erosion is caused by small impacts as rocksknock into each other and chip pieces off.

Impactspecialist Jonti Horner from the UK's Open University agrees with Gyula. "Theresults make sense," he says. "Catastrophic impacts create a hugeslew of fragment shapes, like the shards of a broken bottle. The debris thenare weathered over time and smoothed towards sphericality by small impacts."

Impactsare part of the fundamental processes in our solar system. They were part ofthe planet formation process 4.5 billion years ago, and stilloccur today. "Sometimes astronomers have to be archeologists, too,"says Gyula. "This work is a fine example of how we can deduce abillion-year process from the world we observe today."

Hopefully,this research will not only teach us more about how the solar system operates,but will help us prepare for future impact events. Learning all we can aboutasteroids could help us avoid disaster if we ever detect a large, fast-movingone on a collision coursewith the Earth.

Lee Pullen is a science writer and communicator from the city of Bristol, UK. He has a degree in Astronomy and a master’s in Science Communication. He has written for numerous organizations, including the European Space Agency and the European Southern Observatory. In his spare time Lee enjoys taking photos of the night sky, and runs the website Urban Astrophotography.