NASA Spots Mysterious 'Spider' on Mercury

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A whole new side of Mercury hasbeen revealed in pictures taken by NASA's MESSENGER probe, which flew by thetiny planet two weeks ago in the first mission to Mercury in more than threedecades.

MESSENGER skimmed only 124 miles(200 kilometers) over Mercury's surface on Jan. 14, in the first of three passes it will make before settling into orbit March18, 2011.

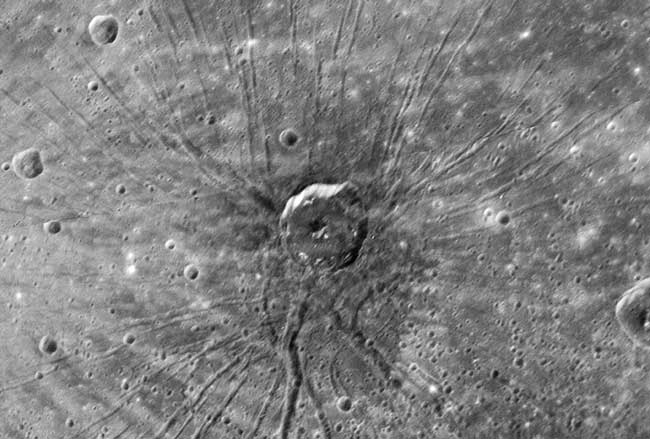

The photos, released today,include one of a feature the scientists informally call "the spider,"which appears to be an impact crater surrounded by more than 50 cracks in thesurface radiating from its center.

Article continues belowScientists are perplexed by thisstructure, which is unlike anything observed elsewhere in the solar system.

"It's a real mystery, a very unexpected find,"said Louise Prockter, an instrument scientist at the Johns HopkinsUniversity Applied Physics Laboratory, which built the probe for the $446million NASA mission. She said whatever event created the spider "isanybody's guess," but suggested perhaps a volcanic intrusion beneath theplanet's surface led to the formation of the troughs.

The last time NASA sent a probeto Mercury was in 1975, when the Mariner 10 spacecraft flew by the planet threetimes. MESSENGER'S first flyby gave scientists the first glimpses of Mercury'shidden side, the 55 percent of its surface that was left uncharted by Mariner10.

MESSENGER, short for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment,GEochemistry, and Ranging, also measured another peculiar element of Mercury —its magnetic field. Earth has a magnetic field surrounding it that acts as aprotective bubble shielding the surface from cosmic rays and solar storms. Butscientists were shocked when Mariner 10 discovered a magnetic field at Mercury,too.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The only other example in our solar system of an Earth-likemagnetosphere is tiny Mercury," said Sean C. Solomon, MESSENGER PrincipalInvestigator from the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

MESSENGER was able to fly through the magnetic field andtake detailed measurements that scientists hope to use to discover the originsof the inexplicable magnetosphere.

Scientists have been poring overmore than 1,200 new images sent by seven instruments on the probe, and they areexcited to gain new insight into the composition of Mercury's surface, theplanet's history, and whereits atmosphere comes from.

"On the eve of the encounter I couldn?t sleep atall," said Robert Strom, a MESSENGER science team member who also workedon the Mariner 10 mission. "I've waited 30 years for this. It didn?tdisappoint at all. I was astounded at the quality of these images. It dawned onme that this is a whole new planet that we're looking at."

The satellite will further probe Mercury'smysteries in a second pass over the planet in October, followed by a thirdflyby in September 2009.

The probe has traveled 4.9billion miles (7.9 billion-kilometers) since it launched in August 2004. On itsjourney it soared by Earth once and Venus twice, offering gorgeous views ofthese planets as well. In 2011 MESSENGER will become the first spacecraft toorbit the closest planet to the Sun.

- VIDEO: MESSENGER at Mercury

- IMAGES: Explore the Planet Mercury

- VIDEO: MESSENGER Probe Views Earth in Flyby

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.