Black Hole Caught in an Eclipse

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A recently observed black hole eclipse is giving astronomers a chance to test key predictions about the swirling disk of material that surrounds it.

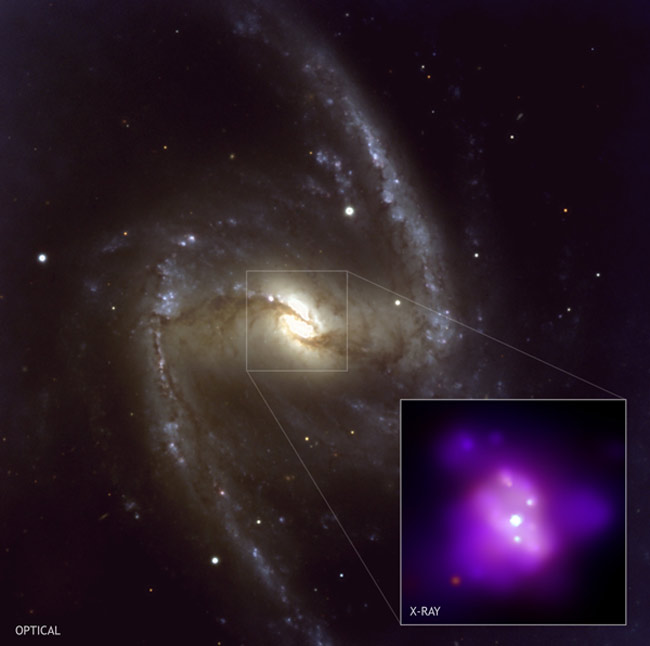

Astronomers spotted a cloud of interstellar gas as it passed directly in front of NGC 1365, a galaxy located 60 million light-years away that contains a supermassive black hole at its center.

Scientists think the supermassive black hole, also called an active galactic nucleus, or AGN, is fed by a steady stream of material swirling around it in the form of a so-called accretion disk.

Article continues belowBlack holes can't be seen, because matter and light that enter them do not come out. Astronomers detect them by noting their gravitational effects on surrounding material. AGNs are even more difficult to study because they are enshrouded by thick shrouds of glowing gas and dust.

Even more challenging, the accretion disk of NGC 1365 is too small for astronomers to resolve directly with a telescope. But the eclipse allowed astronomers to estimate its size by measuring how long its X-ray radiation was blocked by the passing cloud.

Using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, researchers observed NGC 1365 six times over a course of two weeks in April 2006. During five of the observations, high energy X-rays generated by swirling material in the accretion disk was visible. However, in the second observation-which corresponded to the eclipse-no radiation could be detected.

"For years, we've been struggling to confirm the size of this X-ray structure," said study team member Guido Risaliti of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the Italian Institute of Astronomy (INAF). "This serendipitous eclipse enabled us to make this breakthrough."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Size estimate

The researchers now think the black hole's accretion disk is about seven AU in diameter. One AU is equal to the distance between the Sun and Earth. This suggests the disk is about 2 billion times smaller than NGC 1365 itself, and only about 10 times larger than the estimated size of the black hole's event horizon, the sphere inside which everything is trapped. The finding is consistent with theoretical predictions.

The eclipsing cloud that passed in front of NGC 1365 was located one-hundredth of a light-year from the black hole's event horizon.

"Thanks to this eclipse, we were able to probe much closer to the edge of this black hole than anyone has been able to before," said study team member Martin Elvis, also of CfA. "Material this close in will likely cross the event horizon and disappear from the universe in about a hundred years, a blink of an eye in cosmic terms."

- Space News TV: Watch it Now

- Multimedia: All About Black Holes

- Vote Now: The Strangest Things in Space

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.