Newfound Data Could Solve NASA's Great Gravity Mystery

NEW YORK– It’s been years since NASA last heard from either of its twoPioneer probes hurtling out of the solar system, but scientists are stilldebating the source of an odd force pushing against the outbound spacecraft.

Dubbed the PioneerAnomaly, the unexplained force appears to be acting against NASA’sidentical Pioneer 10 and 11 probes, holding them back as they head away fromthe Sun.

Whether that force stems from the probes themselves, something exoticlike darkmatter, or some new facet of physics or gravity,remains in doubt.

But awealth of newly recovered data and telemetry, spanning decades of observationsby both Pioneer 10 and 11, may yield the final answer to whether conventionalphysics or perhaps something new is at work on the two spacecraft. An answer couldarise from the new data after about a year of analysis by an international teamof researchers.

“Iwould like to see this story reach its finality,” said Slava Turyshev, an astrophysicistwith NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) who has spent the last 14years—some of it on his own time—studying the Pioneer Anomaly."So if it’s conventional physics, that’s fine and we can allgo about our daily business. But if it’s something else, there may beanother page.”

He andother fellow devotees discussed the astrophysics oddity late Monday during theSeventh Annual Asimov Debate here at the American Museum of Natural History.

Turyshev’s international team includes researchers from all Pioneer Anomaly camps,with some learning towards a conventional physics explanation while otherstrend toward the unknown fringe. Still other researchers have their ownopinions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“If Iwere a betting man, which I am not, I would bet a whole case of cranberry juicethat the Pioneer Anomaly will have an ordinary explanation that is within knownphysics,” said Irwin Shapiro, an astrophysicist at Harvard Universityunaffiliated with the Pioneer Anomaly research team, during the debate.

Shapirosaid that the number of actual instances in whichoddities like the Pioneer Anomaly have opened pathways to fundamentally newphysics are rare, and that ongoing studies may yet yield a conventionalexplanation.

Perplexingpush

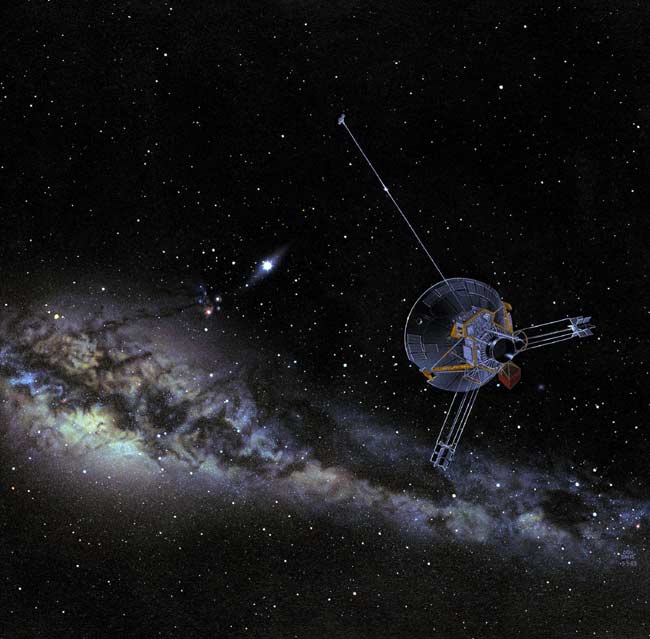

Launched in1972 and 1973, Pioneer 10 and 11 are both billions of miles from Earth as theyzoom out of the solar system in opposite directions.

As of Feb.6, Pioneer 10 was about 92.12 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and headedtowards the constellation Taurus. One AU is the distance between the Earth and Sun, or about 93 million miles (150million kilometers).

Researchersfirst noticed the Pioneer Anomaly as a navigation discrepancy while bouncingmicrowaves off each Pioneer probe as they moved farther from Earth. They foundan unexpected drift in each probe’s Doppler frequency, one so small thatthe three-axis stabilized probes like NASA’s Voyagerspacecraft—also headed out of the solar system—may have drowned itout with their in-flight activities.

The Dopplereffect is the shortening or lengthening of waves, suchas the pitch change of an ambulance as it approaches, races past, then headsaway from you.

“Wehad a fitting model and it had all the effects in it that would influence thespacecraft out in interstellar space, except that it didn’t work,”said John Anderson, a retired JPL researcher who first discovered the PioneerAnomaly. “And all we had to do to make it work was to add a constantacceleration towards the Sun.”

Thediscrepancy found that Pioneer 10 and 11 were each about 240,000 miles (400,000kilometers) closer to the Sun than they should be according to the currentunderstanding of gravity. Isaac Newtondescribed gravity as a force that weakens with distance, and the Pioneer probesare speeding out of the solar system at about 30,000 miles (48,280 kilometers)per hour.

“ThePioneer spacecraft conducted the largest ever gravitational experiment thathumanity attempted to test Newton’s Law, and it failed,” Turyshev told SPACE.com.“If we will identify an anomaly due to conventional physics thermalmechanism or propulsion or a combination there off, that’s a major event.”

Finding aphysical source will not only prove Newton right, but also allow engineers tocancel out the Pioneer Anomaly on future spacecraft to make them more stable,added Turyshev, who said that he is striving toremain unbiased to the anomaly’s cause.

Researcherswant to determine whether heat from Pioneer probes’ electronics or twonuclear power sources—known as radioisotope thermal generators (RTGs)—could be emitting infrared photons that thensmack into the spacecraft’s dish-like main antenna, causing a recoileffect that Turyshev likened to sunlight striking asolar sail.

Analysisand modeling of how the Pioneer 10 spacecraft emits heat from various sources,including its RTG, found that they account for between 55 percent and 75percent of Pioneer Anomaly, said Gary Kinsella, agroup supervisor for spacecraft thermal engineering and flight operations atJPL.

“We’rereally encouraged by the preliminary results and we think we’re goingdown the right track,” Kinsella said during theMonday discussion.

Edward Belbruno, a former JPL researcher and gravitational trajectory expert at PrincetonUniversity who also served the panel but is unconnected with the anomaly research, saidthat another possible explanation for the Pioneer Anomaly rests in the mass of the Milky Way galaxy, which – when taken to account –yielded the exact acceleration change for Pioneer 10 as that observed. While hefound that the technique did not yield a specific direction for theacceleration, it may shed some insight into the anomaly and warrants furtherstudy, Belbruno added.

Recovereddata

Duringtheir first PioneerAnomaly analysis, researchers relied on data that spanned about 11.5 yearsof Pioneer 10’s mission, though they only had about four years worth forPioneer 11.

After anexhaustive search sponsored by the Planetary Society, Turyshevand his team recovered complete telemetry data sets for both Pioneer probes, aswell as about 30 years of data for Pioneer 10 and a 20-year set for Pioneer 11.

Much of thedata sat inert, recorded on about 400 magnetic tapes in deep storage at JPL.Altogether, it included almost 40 Gigabytes of Pioneer 10 and 11 mission data,or about the equivalent of a half hour of high-definition television (HDTV)programming from your local cable TV provider.

Transferringthe data from 9-track magnetic tapes to a modern digital format, and screeningit to reduce artifacts and other corrupted material, has proven time-consumingfor Pioneer Anomaly researchers. But Turyshev remainsconfident that once the information is ready for analysis, the anomaly shed newsecrets.

He is alsokeeping a close watch on NASA’s NewHorizons probe, which may one day show signs of the anomaly as it heads outbeyond Pluto’s orbit after 2015, but only if the mystery force is foundto be an actual effect.

“Weare truly in a unique situation now with the recovery of the new data assets,”Turyshev said. “Once this data set is analyzed,let’s talk then.”

- Top 10 Unexplained Phenomena

- Voyager 2 Detects Odd Shape of Solar System's Edge

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.