Powerful Black Hole Jet Explained

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

While we may never know what it looks like inside a blackhole, astronomers recently obtained one of the closest views yet. The sightingallowed scientists to confirm theories about how these giant cosmic sinkholesspew out jets of particles travelling at nearly the speed of light.

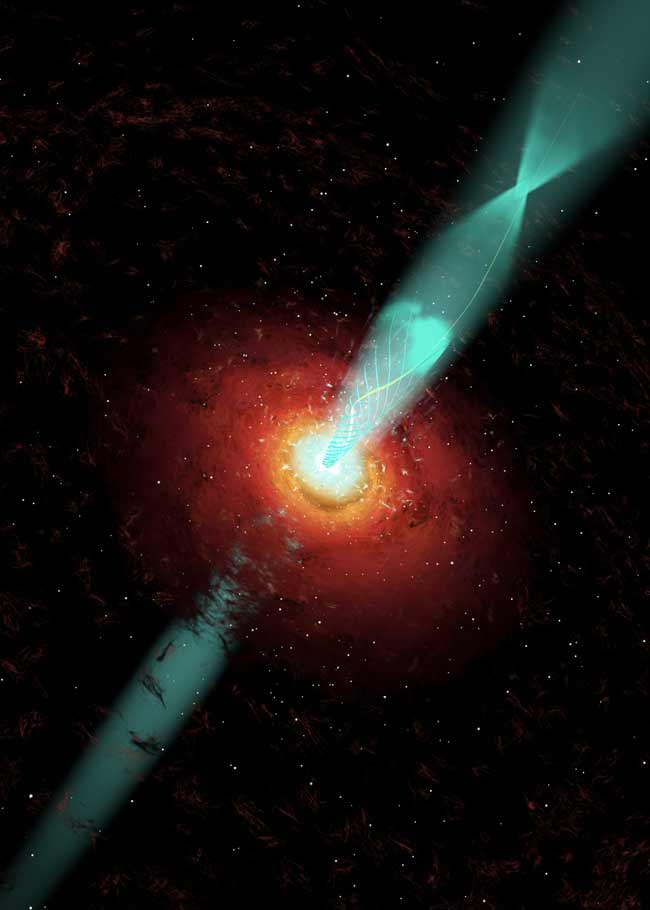

Ever since the first observations of these powerful jets,which are among the brightest objects seen in the universe, astronomers have wonderedwhat causes the particles to accelerate to such great speeds. A leading hypothesissuggested the blackhole's gigantic mass distorts space and time around it, twisting magneticfield lines into a coil that propels material outward.

Now researchers have observed a jet during a period of extremeoutburst and found evidence that streams of particles wind a corkscrew pathaway from the black hole, as the leading hypothesis predicts.

Article continues below"We got an unprecedented view of the inner portion ofone of these jets and gained information that's very important to understandinghow these tremendous particle accelerators work," said Boston University astronomer Alan Marscher, who led the research team. The results of the studyare detailed in the April 24 issue of the journal Nature.

The team studied a galaxy called BL Lacertae (BL Lac), about950 million light years from Earth, with a central black hole containing 200million times the mass of our Sun. Since this supermassive black hole's jetsare pointing nearly straight at us, it is called a blazar (a quasar is oftenthought to be the same as a blazar, except its jets are pointed away from us).

The new observations, taken by the National ScienceFoundation's Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) radio telescope, along with NASA'sRossi X-ray Timing Explorer and a number of optical telescopes, show materialmoving outward along a spiral channel, as the scientists expected.

These data support the suggestion that twisted magneticfield lines are creating the jet plumes. Material in the center of thegalaxy, such as nearby stars and gas, gets pulled in by the black hole'soverwhelming gravity and forms a disk orbiting around the core (the material'sinertia keeps it spiraling in a disk rather than falling straight into theblack hole). The distorted magnetic field lines seem to pull charged particlesoff the disk and cause them to gush outward at nearly the speed of light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We knew that material was falling in to these regions,and we knew that there were outbursts coming out," said University of Michigan astronomer Hugh Aller, who worked on the new study. "What's reallybeen a mystery was that we could see there were these really high-energyparticles, but we didn't know how they were created, how they were accelerated.It turns out that the model matches the data. We can actually see the particlesgaining velocity as they are accelerated along this magnetic field."

The astronomers also observed evidence of another phenomenonpredicted by the leading hypothesis ? that a flare would be produced whenmaterial spewing out in the jets hit a shock wave beyond the core of the blackhole.

"That behavior is exactly what we saw," Marschersaid.

- VIDEO: Black Hole Blazar Jets

- VIDEO: Black Holes - Warpers of Time and Space

- All About Black Holes

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.