Violent Star Collision Triggers Cosmic Fireworks Display

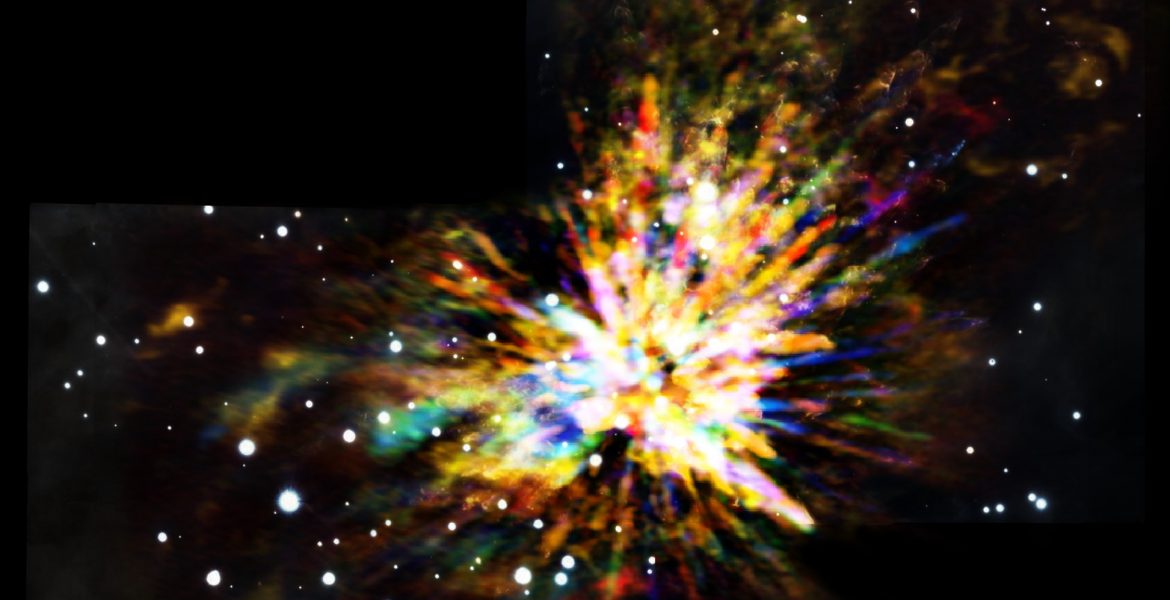

The collision of two young stars triggered a spectacular stellar explosion like a fireworks show on the Fourth of July, a new study shows.

This cataclysmic event took place roughly 500 years ago, from Earth's perspective, in a region known as the Orion Molecular Cloud 1 (OMC-1), located about 1,500 light-years from Earth. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, astronomers captured a stunning view of the remains of the brilliant burst.

OMC-1 is a dense and active stellar nursery. Over time, two adolescent protostars roaming about the molecular cloud gradually wandered too close to each other and collided, sending streams of gas, dust and other unborn star material out into interstellar space "at speeds greater than 150 kilometers per second," according to the recent study. This event "released as much energy as our sun emits over the course of 10 million years," scientists said in a statement from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO). [Best Space Fireworks Photos Ever]

"What we see in this once-calm stellar nursery is a cosmic version of a Fourth of July fireworks display, with giant streamers rocketing off in all directions," John Bally, lead author of the study from the University of Colorado Boulder, said in the statement.

As young stars form in dense regions of a massive cloud of gas, such as OMC-1, they are able to drift about randomly. However, if the newborn stars slow down, they begin to fall toward a common center of gravity — and if they get too close before dispersing into the galaxy, they experience violent collisions, such as that observed by the ALMA telescopes. This type of stellar explosion is generally short-lived, and the remnants are visible for only centuries, scientists said in the statement.

"Though fleeting, protostellar explosions may be relatively common," Bally said in the statement. "By destroying their parent cloud, as we see in OMC-1, such explosions may also help to regulate the pace of star formation in these giant molecular clouds."

Previous observations made using the Submillimeter Array in Hawaii and the Gemini South telescope in Chile revealed the explosive nature of this stellar burst and the structure of the remnant streams of gas, which extend nearly a light-year from end to end, scientists said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study, however, provides insight into the underlying force of the blast, as well as the "distribution and high-velocity motion of the carbon monoxide (CO) gas inside the streamers," scientists said. Their findings, published March 3 in The Astrophysical Journal, shed new light on how stellar collisions like this may affect star formation in other areas of the galaxy, the researchers said.

"People most often associate stellar explosions with ancient stars, like a nova eruption on the surface of a decaying star or the even more spectacular supernova death of an extremely massive star," Bally said in the statement from the NRAO. "ALMA has given us new insights into explosions on the other end of the stellar life cycle, star birth."

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.