Success! Japanese Spacecraft Arrives at Venus 5 Years After 1st Try

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A Japanese Venus probe took advantage of its long-awaited second chance.

Japan's Akatsuki spacecraft has arrived in orbit around Venus, five years after an engine failure scuttled its first attempt, Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) officials announced today (Dec. 9).

The $300 million Akatsuki mission launched in May 2010 along with JAXA's IKAROS (Interplanetary Kite-craft Accelerated by Radiation Of the Sun) spacecraft, which became the first probe ever to deploy and use a solar sail in interplanetary space. [See photos of Venus and IKAROS from Japan's Akatsuki]

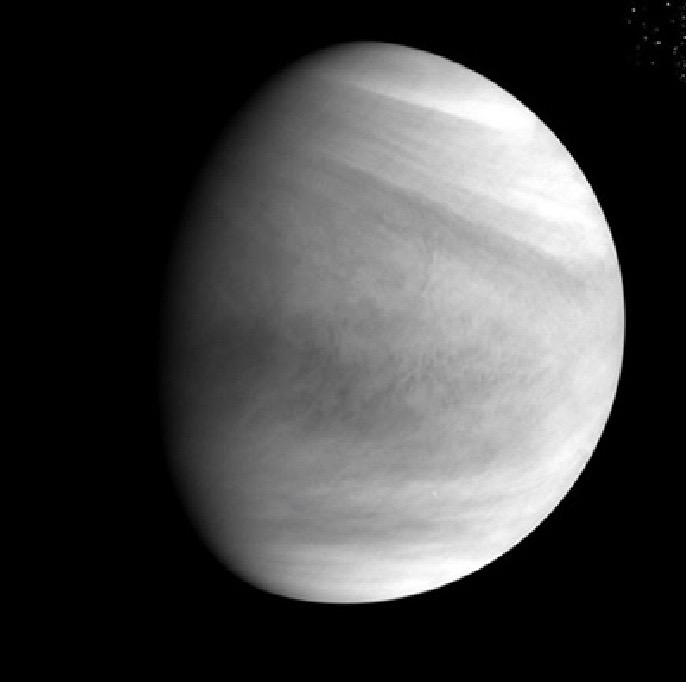

Akatsuki was originally supposed to enter Venus orbit on Dec. 6, 2010, then study the planet's clouds, weather and atmosphere from above for at least two years to learn more about how the world became so hot and seemingly inhospitable to life. But the spacecraft's main engine conked out during a crucial orbit-insertion burn, and Akatsuki went zooming off into space.

The spacecraft — whose name means "Dawn" in Japanese — had been circling the sun for five years, waiting for another shot at Venus. That shot came exactly five years to the day after the first opportunity.

On Sunday (Dec. 6), Akatsuki fired its small attittude-control thrusters for 20 minutes to achieve Venus orbit (its main engine was pronounced dead long ago). After a few days of calculations and computations, mission controllers have now determined that the maneuver worked.

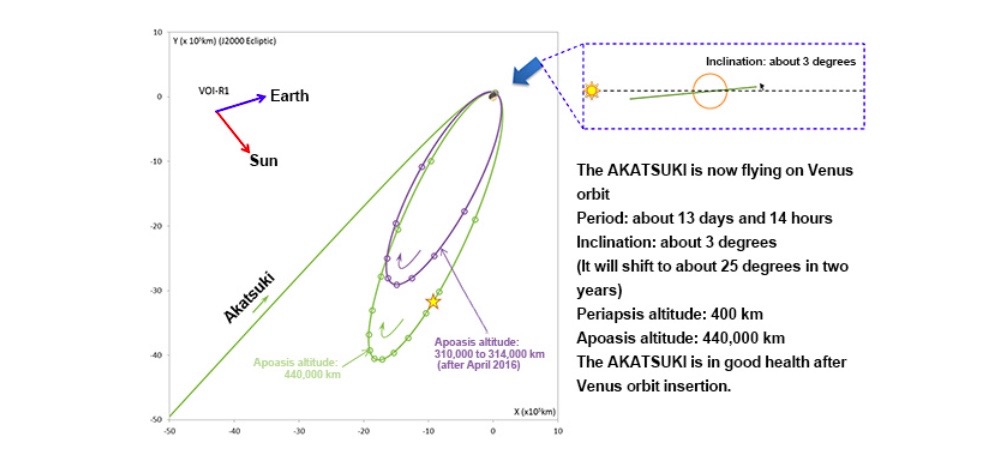

"The orbit period is 13 days and 14 hours. We also found that the orbiter is flying in the same direction as that of Venus's rotation," JAXA officials wrote in a statement today. "The Akatsuki is in good health."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Akatsuki's current path takes it as close as 250 miles (400 kilometers) to Venus, and as far away as 273,000 miles (440,000 km), officials added. This orbit is much more elliptical than the one Akatsuki was supposed to achieve five years ago, which featured a period of 30 hours and an apoapsis (most distant point from Venus) of 50,000 miles (80,000 km) or so.

Akatsuki's handlers will soon deploy and test three of the probe's six instruments, to make sure they're working properly — the other three are already known to be in good condition — and then conduct initial observations with all of this scientific gear for about three months, JAXA officials said.

At the same time, Akatsuki will maneuver to a less-elliptical final science orbit with a period of about nine days and an apoapsis around 193,000 miles (310,000 km). The probe should achieve that orbit, and commence regular operations, by April 2016.

Despite the long delay, the drama and the highly elliptical orbit, Akatsuki should still be able to accomplish most of its science goals, JAXA officials have said.

Akatsuki is the second interplanetary mission in Japan's history. The country's first, the Nozomi Mars probe, failed to arrive as planned at the Red Planet in 2003. In 2007, Japan's Kaguya orbiter successfully launched to the moon to study the lunar surface from orbit. Kaguya's mission ended in 2009 and it ultimately crashed into the moon's surface.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.