Bringing Pluto into Focus: Q&A with New Horizons PI Alan Stern

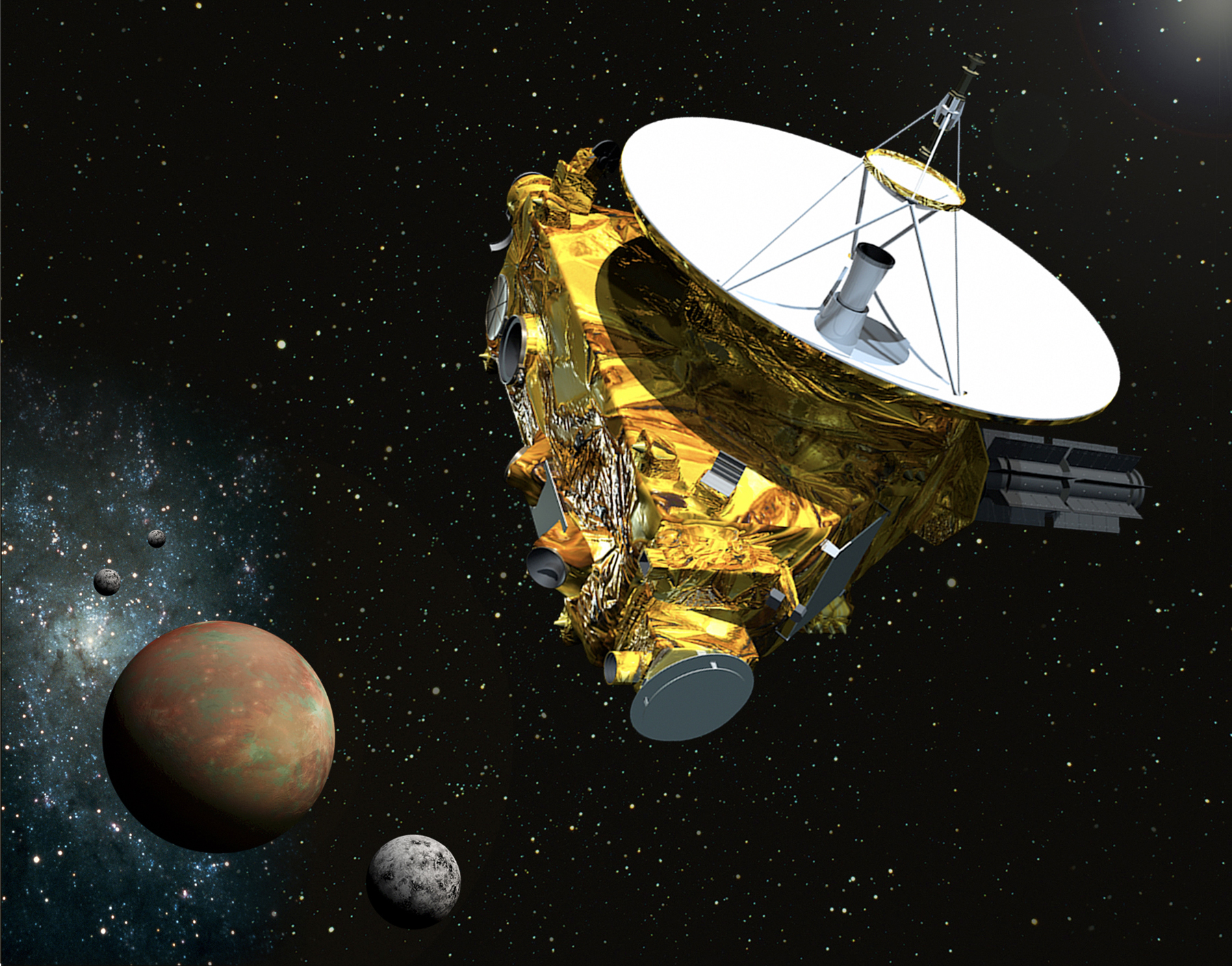

NASA's New Horizons probe is about to lift the veil on Pluto.

New Horizons is streaking toward a close flyby on July 14, when it will zoom within just 8,500 miles (13,600 kilometers) of Pluto. The spacecraft will return the first-ever up-close looks at the dwarf planet, which has remained largely mysterious since its 1930 discovery.

Though the closest approach remains more than five months away, New Horizons has already entered the "encounter phase" of operations. Indeed, on Sunday (Jan. 25), the probe began imaging Pluto with its telescopic camera to ensure it stays on the correct trajectory. (The first course-correcting engine burns, if necessary, would likely take place in March.) [Photos from NASA's New Horizons Pluto Probe]

Space.com caught up briefly with New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern last month at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco to discuss this new phase of the $700 million mission.

Space.com: How does it feel to be on Pluto's doorstep now, nine years after blasting off? [New Horizons launched in January 2006.]

Alan Stern: I've worked on this mission for 25 years. So now, it feels incredible. It feels surreal. When you've talked about something in the future tense for as long as you can remember, and now — even though you know intellectually there'll come a time when it's in the present, it feels surreal.

And a little bit scary, only because, no matter how much you practice, you can't practice everything, or practice perfectly. As ready as we are, as talented as this team is, we are flying into the unknown.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Every mission has to deal with that uncertainty, that fear, on some level. But is it more pronounced with New Horizons, because you guys are going so far afield and studying an unexplored world?

Every mission has life-or-death moments. We had a previous one; it's called launch. I knew when we launched that everything I'd worked on for 17 years was riding on that day, and about one hour in that day. Every mission has to deal with that, and missions have other moments, too. A good example is the Curiosity landing — seven minutes of terror, they called it.

The difference is that Pluto is so far away. I have no doubt that if Curiosity had a bad day, there would have been another Mars rover in people's lifetimes. I don't know if we could mount another mission to Pluto.

Even if you don't have to litigate it — even if someone just wrote a check the next day — people would probably say, "Is that how we want to spend our money today? Do we want to start this 20-year adventure all over? Is it really worth it?" and so on. So there's more riding on it for that reason as well.

It's bad enough if you lose your mission; this is probably our only chance to do the [Pluto] program. I don't have two spacecraft, and sending a replacement, you're talking 2030s, best-case.

What do you expect to see at Pluto?

I've been on 26 space missions; they range from suborbital to orbital to shuttle experiments to planetary missions. And I've never done anything like this. And here's the thing: No one in my generation has done anything like this. We haven't done a first reconnaissance of a planet since [NASA's Voyager 2 probe flew by Neptune in] 1989. So I don't quite know what to expect.

I don't make predictions; it'll be here soon enough. And every planetary flyby, every first reconnaissance, has proven us so naïve — our conceptions based on Earth-based data. No one predicted Mercury would be a planetary core with the mantle stripped off. No one predicted volcanoes on the Jovian moons, or oceans on the inside of them. I can tell you, for every single planet, huge "we never guessed that" things.

So, connecting those dots, I have to say it's futile to make these predictions. We're not only going to a new place — we're going to a new class of place.

That's a point that you and others on the mission have stressed: There are probably hundreds of worlds like Pluto in the Kuiper Belt [the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune], and New Horizons is going to give us our first good look at these mysterious objects.

That's right. There's nothing analogous to this.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.