Pulsing Stars Help Map Milky Way's Outer Reaches

New observations of five young variable stars reveal a strange thickening in farflung regions of the Milky Way galaxy.

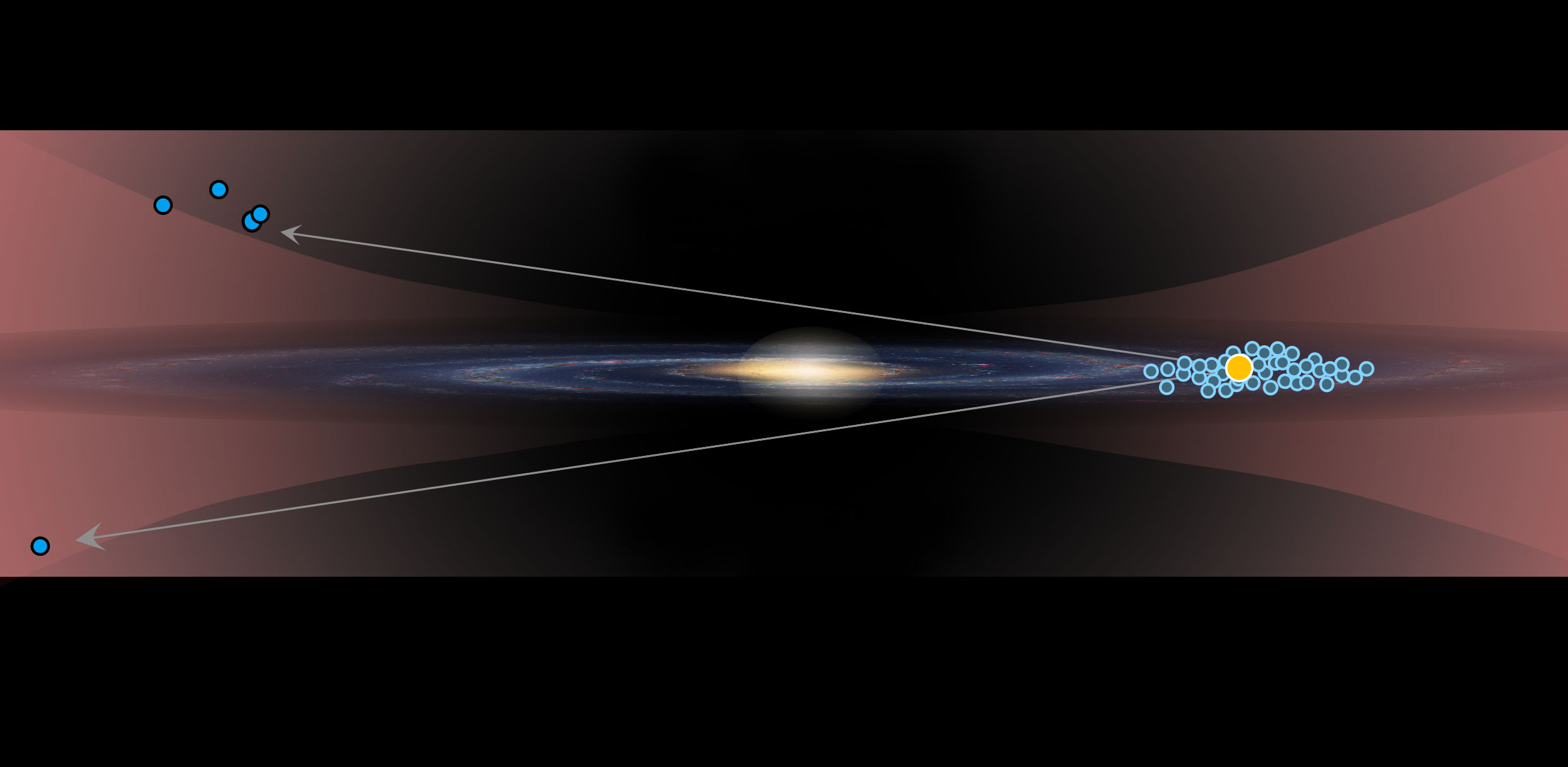

Known as Cepheid variables, the stars are positioned above and below the plane of the galaxy's disk. That position, combined with the stars' young age, indicates a warp to the arm that was previously suggested by observations of dust, but had not been shown by the presence of stars.

Stars on the other side of the galactic center can be challenging for scientists to observe, as the amount of interstellar dust increases at greater distances. A team of astronomers utilized two telescopes at the South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO) to determine that the five Cepheid variables lie on the far side of the bulge of material in the heart of the Milky Way, above and below the galactic plane. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy (Gallery)]

Young stars

With a firm relationship between their brightness and their pulsation rate, Cepheid variables often serve as "standard candles" to measure distances within the galaxy. By comparing how bright such a star is to how bright it should be if an observer stood next to it, astronomers can compute how far away the object lies.

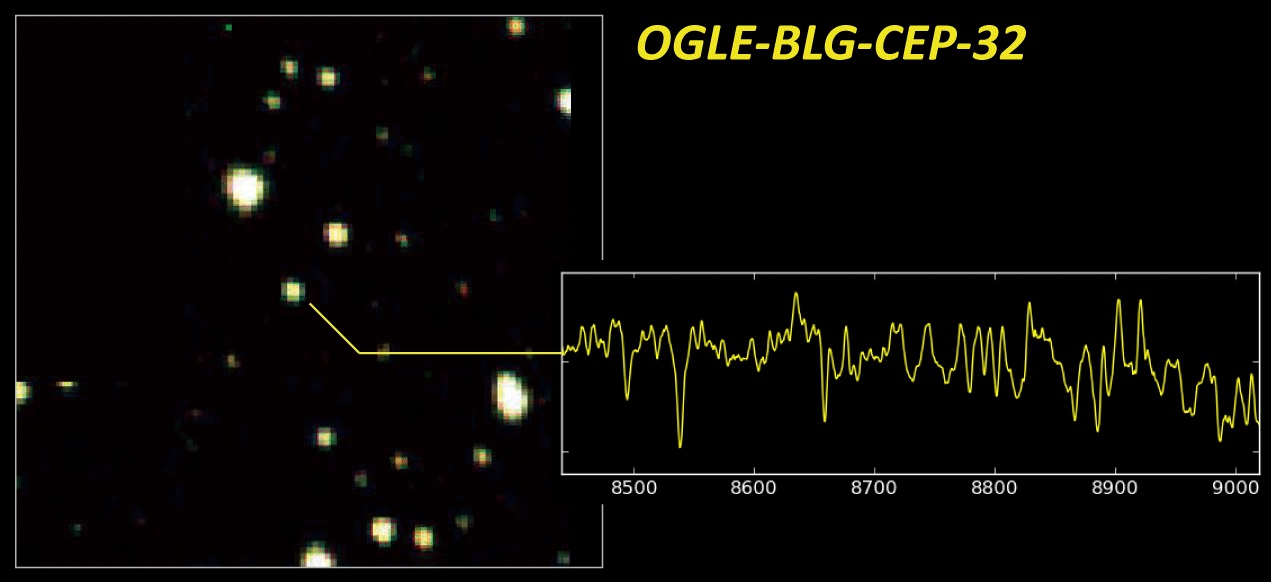

A team of astronomers led by Michael W. Feast, of the University of Cape Town in South Africa, studied several possible Cepheid variables. The list came from the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE), which monitors the light from approximately one billion stars in the sky to create a catalog of more than 400,000 stars that regularly change in brightness.

Of the original 32 stars studied, Feast's team classified five as true Cepheid variables and established their distances, as well as how quickly they travel. Although the stars lie in a stream associated with the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, the astronomers quickly determined that the objects were traveling too slowly to be a part of that branch. Nor could they be part of the Milky Way's bulge, as they lie too far from the galactic center.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The age of the variable stars ruled out the idea that they are isolated outliers. At only about 150 million years old, the Cepheids are young stars, while single stars tend to be older. Instead, the variable stars form part of a disk that thickens as it extends out of the galaxy.

"Cepheids and spiral arms are both young parts of the galaxy, so they tend to be found together where star formation has occurred recently," study co-author Patricia Whitelock, also of the University of Cape Town, told Space.com by email.

Previous studies of hydrogen gas suggested that the disk of the Milky Way galaxy flares outward rather than levels off, but no previous observations of stars could confirm the idea.

"We found the Cepheids at exactly the distance predicted for this increase in disk thickness," the team writes in the new study, which was published online today (May 14) in the journal Nature.

This implies that the flare consists not only of gas but also of stars, Whitelock said — a characteristic that was not previously known.

Dark matter warps the disk?

The cause behind the flaring remains uncertain, but one possible explanation is the presence of dark matter.

A halo of dark matter surrounds galaxies like the Milky Way. One predicted consequence is that the diffuse matter in the outer disk is more strongly affected by this mysterious stuff, which neither absorbs nor emits light, but makes up about 80 percent of the material universe.

Such warping in other galaxies could theoretically help in measuring their dark matter distribution, researchers said.

Thus far, scientists have used gas to trace the flaring in the Milky Way's outer disk. However, the diffuse gas is difficult to track, and the models that derive its distribution in the galaxy vary greatly. By studying stars such as the Cepheid variables, astronomers can nail down a more detailed understanding of the shape of the Milky Way.

Although Feast's team will not continue to hunt for Cepheid variables, that doesn't mean more won't be found.

"We expect that new surveys for variable stars will turn up similar stars in other parts of the galaxy," Whitelock said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky