Want to see the Super Flower Blood Moon? Here's one scientist's tips for the total lunar eclipse.

Every full moon is special, planetary geologist Brett Denevi says, and this is the first total lunar eclipse of 2022.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Editor's note: The total phase of the Super Flower Blood Moon lunar eclipse has ended. You can read our wrap story on the first total lunar eclipse of 2022.

A lunar scientist shared the science behind why the Super Flower Blood Moon lunar eclipse turns red, and what to expect for the epic sky event.

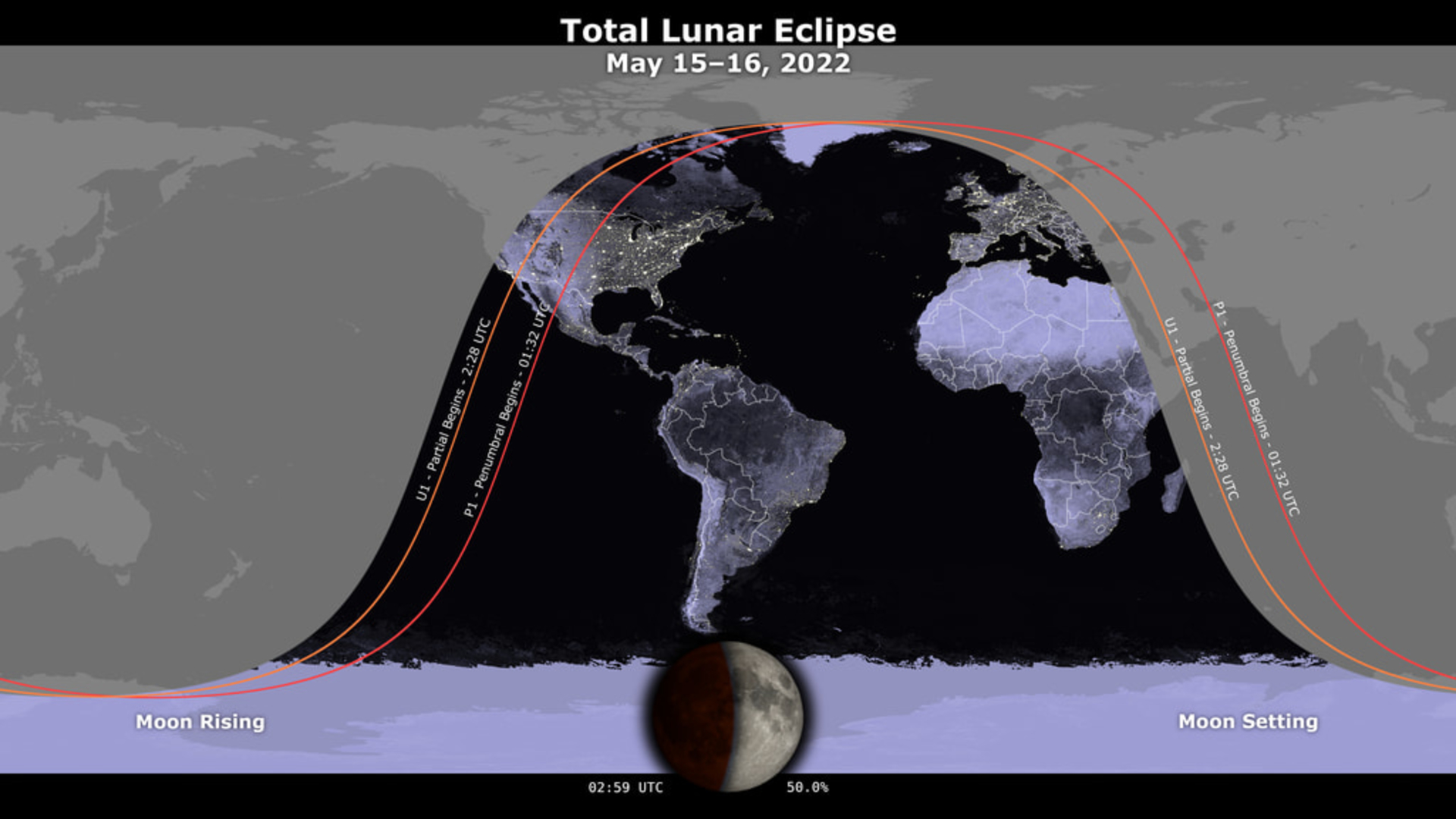

On Sunday (May 15), the moon will pass into the deep umbral shadow of the Earth in a band of visibility across the Americas, Antarctica, Europe, Africa and the east Pacific. The Super Flower Blood Moon lunar eclipse, as it's called, will be the first total lunar eclipse of 2022.

You can watch the lunar eclipse online in a series of webcasts, starting around 9:30 p.m. EDT (0130 GMT).

Related: What time is the Super Flower Blood Moon eclipse?

Looking for a telescope for the lunar eclipse? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Skywatchers are calling tonight's lunar eclipse as Super Flower Blood Moon because the full moon is occurring near its perigee, or closest point to Earth in its orbit, for the month, garnering it a "supermoon" nickname. May's full moon is known as the Full Flower Moon, a traditional name for May's full moon, according to Almanac.com, citing older Native American customs in parts of the United States.

The supermoon's definition is more complicated, as a Brett Denevi, a planetary geologist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, told Space.com in a live video interview Friday (May 13).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Every full moon is special, in my books," she said. "But sometimes the moon is a little bit closer to the Earth than other times. So sometimes, it looks a little bit bigger in the sky. This is one of those times that some people call it a supermoon."

A penumbral version of the lunar eclipse is set to happen in New Zealand, eastern Europe and the Middle East, as the moon skirts into the lighter, penumbral shadow our planet casts.

The moon's orbit around the Earth is not a perfect circle. One community definition of a supermoon, first suggested by astrologer Richard Nolle in 1979, cites a supermoon as occurring when the moon's monthly perigee is within 90%of the closest possible approach to Earth. NASA tends to follow that definition.

The 90% rule, however, does not grant May supermoon status (although June's will be). That said, others in the community — such as eclipse scientist Fred Espenak, formerly of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center — say that May's moon is a supermoon if you account for changes in the moon's orbit during each lunar cycle.

Supermoons are tough to judge in the sky, as they are only very slightly bigger than a typical full moon. That said, the blood red that accompanies a lunar eclipse is easy enough for anybody to spot. Denevi explained that the effect happens due to light traveling through the Earth's atmosphere before falling on the moon.

"What you're seeing projected onto the moon [is] just like [when] you see a kind of orangish, reddish glow in the sky on sunset or sunrise on Earth," she said. "That ring of light that you see from the moon is all of the Earth's sunrises, and all of the Earth's sunsets, at once projecting on to the moon."

Related: The stages of the Super Flower Blood Moon of 2022 explained

While the eclipse will have no direct impact for viewers on Earth, there is one lunar spacecraft that NASA always seeks to protect as solar energy stops reaching cislunar (moon-Earth) space for a few hours.

The venerable Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has been working at the moon for nearly 13 years, having launched in June 2009. Denevi is the deputy principal investigator for LRO's camera that takes high-definition images of the surface for lunar science, to find water reservoirs and to map out landing missions.

"Luckily, it has batteries, but we use the the solar panels to charge up the batteries," Denevi said of LRO. "During the eclipse, there's not enough power to run all of the instruments. We prepare by shutting down those instruments. We monitor the spacecraft throughout the eclipse to make sure it's still healthy, it's warm enough. Then as the eclipse ends, we can begin powering back on return to taking data."

LRO's contribution to lunar science has been immense, given it has been in orbit for so many years. To Denevi, she paid tribute to its ability to show the moon as a changing environment, even though parts of the surface are billions of years old.

"Some of those features, we think, may have formed just tens of millions of years ago, which for the moon and for geologic history is actually quite young," she said.

"Then we've also seen new impact craters on the moon that have formed during the mission," Denevi continued. "We can image the moon before they happen. We keep repeat imaging the surface and we can pick up new craters that have formed on the moon just while we've been in orbit."

If you take a photo of the 2021 total lunar eclipse let us know! You can send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

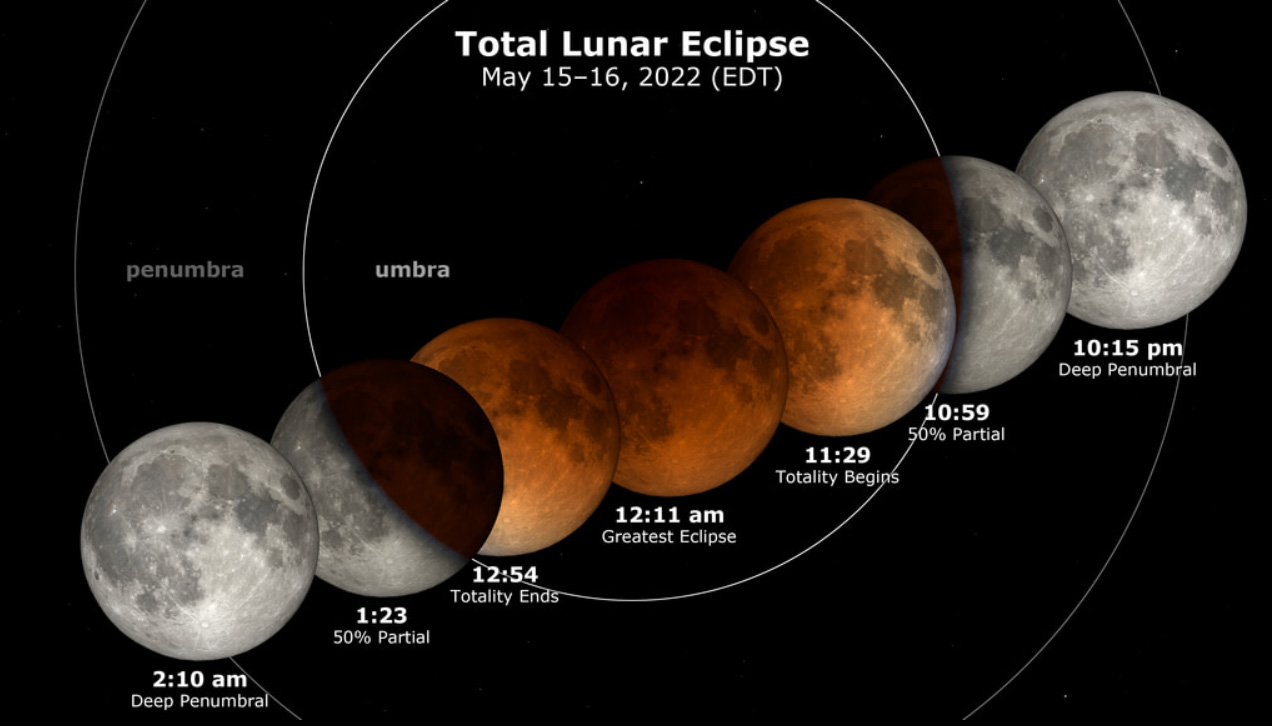

Depending on your location, a partial lunar eclipse begins May 15 at 10:28 p.m. EDT (0228 GMT on May 16). The Blood Moon will reach its peak at 12:11 a.m. EDT (0411 GMT) on May 16 before the lunar eclipse ends at 1:55 a.m. EDT (0555 GMT). The penumbral moon phase of the eclipse will begin about an hour earlier and end about an hour after the partial eclipse, according to TimeandDate.com.

If you can't get outside to view the event, you can also catch livestreams available on YouTube from NASA Science Live, Slooh and TimeandDate.com.

If you're looking to photograph the moon, check out our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography. Read our guides on how to photograph a lunar eclipse, as well as how to photograph the moon with a camera for some helpful tips to plan out your lunar photo session.

NASA's livestream starts at 9:32 p.m. on May 15 (0132 GMT May 16), focusing on moon science, eclipses, and the Artemis program for landing people on the moon. Slooh, an astronomy webcaster, will begin May 15 at 9:30 p.m. EDT (May 16 0130 GMT). TimeandDate will show the entire eclipse, weather permitting, starting at 10 p.m. EDT May 15 (0200 GMT May 16).

This is the first of two lunar eclipses in 2022. The next one will happen Nov. 8, 2022 with at least partial visibility from Asia, Australia, North America, parts of northern and eastern Europe, the Arctic and most of South America, according to TimeandDate.com.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing lunar eclipse photo and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.