New Satellite Beams Back Its 1st Photo of Lightning from Space

A new weather satellite promises to deliver unprecedented data on Earth's lightning, and it has already captured its first spectacular images of storms from space.

Today (March 6), the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released the first observations taken by the satellite's Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) instrument.

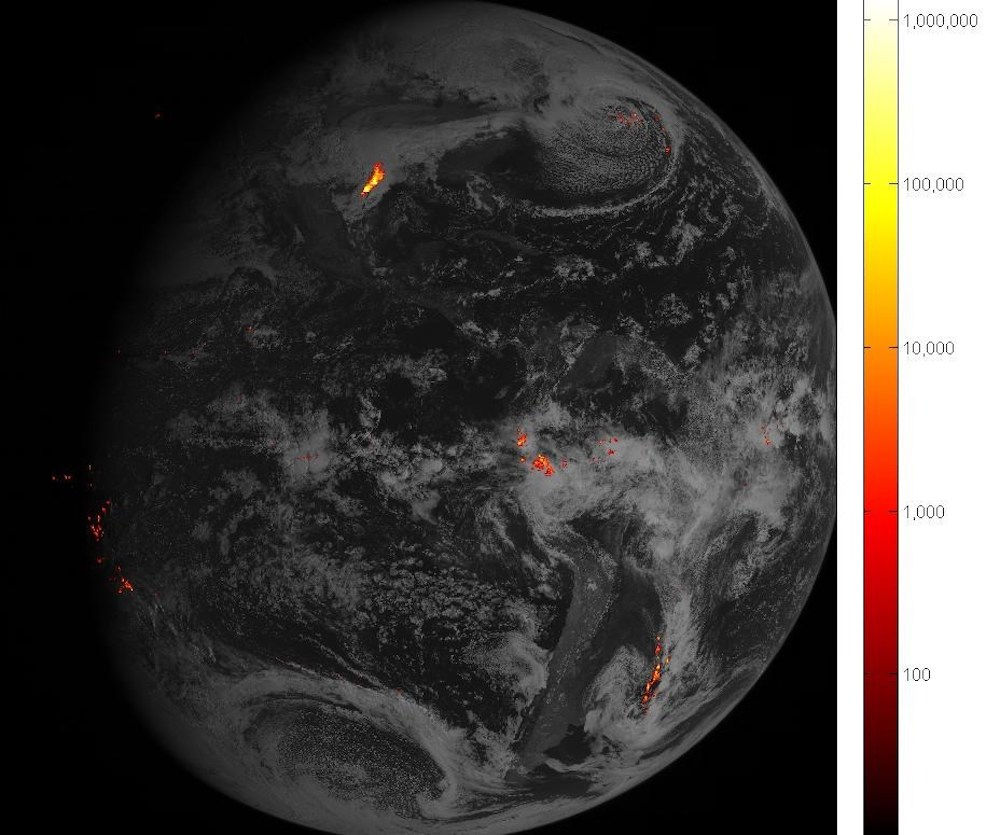

This image combines an hour's worth of lightning data obtained on Feb. 14, according to NOAA. Brighter colors show where more lightning energy was recorded, with the most intense storm system located over the Gulf Coast of Texas on that particular day. [See More Spectacular Images from the GOES-16 Satellite]

The GLM is just one of the scientific instruments on board NOAA's GOES-16 weather satellite, which launched into space in November 2016 and is now orbiting 22,300 miles (35,900 kilometers) away from Earth.

Constantly watching for lightning in the Western Hemisphere, the GLM takes hundreds of images each second. This means that in just its first few weeks online, the instrument has already collected more lightning data than all previous lightning data gathered from space combined, according to a statement from Lockheed Martin, the company that built the GLM.

A rapid increase in lightning is often a good indicator that a storm is intensifying and could produce dangerous weather, according to NASA. Thus, by using the GLM to watch how storms grow and strengthen, weather researchers hope they'll be able to improve severe-weather forecasts and issue flood and flash-flood warnings sooner.

Better lightning maps could even help forecasters and firefighters identify dry areas that are susceptible to lightning-sparked wildfires. The GLM may even be able to look for storms over the ocean that pose a threat to aviators and mariners.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The instrument is the first to observe lightning from geostationary orbit, which means it is always observing the same part of Earth.

"Seeing individual lightning strikes from 22,300 miles away is an incredible feat," Jeff Vanden Beukel, of Lockheed Martin, said in the statement. Beukel noted that the instrument is also monitoring cloud-to-cloud lightning for the first time. This type of lightning typically occurs 5 to 10 minutes or more before potentially deadly cloud-to-ground strikes.

This monitoring will help forecasters issue more precise weather warnings for people on the ground, at sea and in the air, he added.

Other instruments on board GOES-16 include the Advanced Baseline Imager, which captures high-definition images of the planet and recently allowed NOAA to create an updated version of the iconic "Blue Marble" image of Earth.

The satellite is also carrying the Extreme Ultraviolet and X-Ray Irradiance Sensors (EXIS), which can more precisely measure solar flares, and the Space Environment In‐Situ Suite (SEISS), which looks for fluxes of charged particles that could pose a risk to astronauts or satellites.

Original article on Live Science.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.