What Finding Alien Life Could Mean for Earth

Imagine that tomorrow morning scientists tell the world they’ve found evidence for a colony of aliens living only 35 million miles from Earth.

Do you think your neighbors would wig out - stocking up on Ramen noodles, and secluding themselves and the family schnauzer in the basement? Or do you believe most folks would simply mutter “whatever,” and go back to checking out new Facebook friends?

The question’s not altogether fatuous, because this kind of discovery could happen soon, thanks to the efforts of astrobiologists - researchers who study the origin, nature and distribution of life.

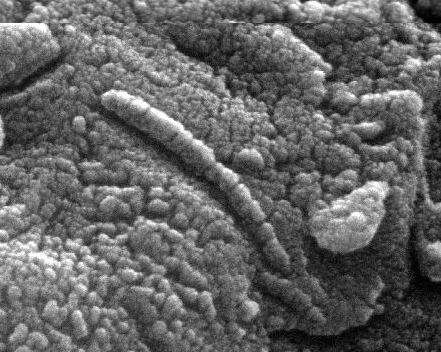

Although we still haven’t found any biological activity elsewhere, it’s hardly inconceivable that before your car gets its next oil change, robot spacecraft could discover a horde of microbes hidden beneath the Martian sands. Or maybe a few years down the road, some astrobiology experiment will stumble across alien pond scum floating in Titan’s rime-frosted lakes, or pick up a radio signal beamed earthward from the star system Gliese 581.

The impact of such news would be significant and, at this point, largely unknown. So to get a better grip on how astrobiological discoveries would play out, the SETI Institute and the NASA Astrobiology Institute recently held a three-day workshop to bring together scientists, ethicists, historians, lawyers, anthropologists, and the media to consider the societal consequences of this type of research.

It’s obvious that three days of conversation is thoroughly inadequate for gauging the cultural repercussions of astrobiology’s wide range of research. So Margaret Race, the organizer of the event and a scientist at the SETI Institute, suggested that the forty-and-more participants simply devise a “roadmap” - a reconnaissance of the issues, if you will. What should we be studying in this field? As the traveling salesmen in The Music Man insisted, “you’ve got to know the territory.”

Well, let me tell you: the territory is immense, and encompasses such dramatic and controversial conundrums as protecting ourselves from errant asteroids (is it OK to deflect an incoming rock just enough to keep it from pulverizing your own country but let it wallop, say, western China?) and dealing with the possibility of synthetic life, cooked up in a lab (should there be controls on such research?)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

I won’t even try to survey the field. But I will offer an example that will keep your brain warm if you ponder it during your ride to work. It’s the scenario that began this short essay, and it will give you some flavor of the type of problems foreseen by the workshop participants.

It goes like this. As zealous followers of space research know, there’s now good evidence for methane floating above the Martian landscape in several regions of the planet. Now there are only two straightforward explanations for this gas: (1) the methane is the consequence of geological activity, such as volcanism, or (2) it’s produced by bacteria-like microbes under the surface. Suppose we were to discover that biology, not geology, is making the methane. This would be big news, because after centuries of imaginative speculation, we would have found real Martians.

Now consider the long-term problems this would pose. Mars, rather than being a natural place for humankind to explore and exploit, would take on a different mien. Suddenly we’d know it has natives.

So what do we do about that? Some would say, “Hey, these Martians are mindless and miniscule. We don’t worry about earthworms at a building site. We won’t worry about these guys.” Of course, samples of this life would be made available for scientific scrutiny, but that’s a different, and short-term, matter. Once the inhabitants had been cataloged and crated, Mars would be open for business. After all, isn’t it human destiny to spread out? Surely we wouldn’t let a messy mass of microbes interfere with our efforts to colonize the Red Planet.

Or would we? Others might say, “Look, the planet has its own ecosystem. Leave it alone. We’ll turn Mars into a nature preserve.” If, like NASA’s Chris McKay, you think that life is special and should be encouraged, you might wish to intervene to give the indigenous Martian life a helping hand; to let it flourish in a way that’s clearly beyond what it’s doing now. In other words, not merely preserve the Martians’ habitat, but improve it.

Those who cotton to third-way approaches might consider fencing off Mars’ inhabited real estate (assuming that it doesn’t lace the entire planet), and limiting human intrusion. It’s unclear, of course, how well this would work, and in any case, any long-term terraforming project would change the climate in the “Martian territories” as well as the rest of this world.

So what would you do? What should humanity do, and how will it decide? And even if there was some sort of international agreement, who would be tasked with enforcing it?

These are not easy questions to answer, and the organizers of the workshop thought it worth getting a head start before the headlines arrive. Consider the reluctance of Nicolaus Copernicus to publish his work a half-millennium ago. Fearful of the reaction of religious zealots, he initially did no more than circulate a small book, without his name on it, outlining his ideas. His magnum opus, De Revolutionibus Orbeum Coelestium, hit the shelves (and, according to popular account, his deathbed) much later. Similarly, Charles Darwin delayed publication of his evolutionary theories, worrying that they would discomfit readers because humankind would no longer be so exceptional. Societal reaction can matter.

The fact is that much of what scientists do won’t change your life very much. A lot of it is like numismatics or canning fruit: specialized activities with only modest cultural impact. But if we find life of any kind beyond Earth, everyone’s going to notice, and our descendants will be affected in profound ways. Exactly how they’ll be affected deserves our consideration now.

Seth Shostak is an astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, who places a high priority on communicating science to the public. In addition to his many academic papers, Seth has published hundreds of popular science articles, and not just for Space.com; he makes regular contributions to NBC News MACH, for example. Seth has also co-authored a college textbook on astrobiology and written three popular science books on SETI, including "Confessions of an Alien Hunter" (National Geographic, 2009). In addition, Seth ahosts the SETI Institute's weekly radio show, "Big Picture Science."