How NASA's Bold Moon Crash Almost Bombed

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Theexistence of ice on the moonwas revealed with a bang last year, when kamikaze spacecraft crashedinto a craterat the lunar south pole, kicking up enough water for researchers tofinallydetect.

Today scientists in six separatestudies announced newfindings from the Oct. 9, 2009 LCROSS moon crash mission. They found,amongother discoveries, substantialamounts of water ice at ground zero for the impact —water that could one day be key to the humanity's future in space.

But as successful as the missionproved in the end, the complicated affair was fraught with uncertaintyand cameperilously close to failure. Now scientists reveal the story of howthey madetheir discovery and what challenges they faced along the way. [10Coolest New Moon Discoveries]

A very coordinated dance

In2009, NASA sent two missions tothe moon at the same time: the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which ismappingthe moon's surface, and LCROSS, short for LunarCrater Observation and Sensing Satellite. It was LCROSS that collidedwith the moon.

Scientists had speculated on theexistence of water on themoon since the 1940s, but it took LCROSS to help kick up significantamounts ofwater to reveal evidence for it within the permanent shadows in acrater at themoon's south pole.

Thescientists wanted as many eyeswatching the impact as possible to squeeze out every drop of knowledgetheycould, which meant finding the right time of day so that as manyobservatoriesin space and spread across thousands of miles on the ground could facethe moonduring the impact.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Inthe end, in addition to LRO inorbit around the moon, 22observatories on theground and four in Earth orbit watchedthe lunar collision.

"Itwas a very coordinateddance between a lot of different parties," saidNASA space scientist Tony Colaprete, who was principal investigator fortheLCROSS mission.

Thetwo-year campaign tocoordinate these ground- and space-based assets spearheadedby JenniferHeldmann and Diane Wooden at NASA in large part involved learning howto watchthe moon in the first place.

"Normally, moonlight is the enemy,always contaminatingour view of the rest of the sky," Colaprete explained. "And itsbrightness made it hard to track with the auto-guidance systems wehad."

Insteadof using "guidestars" as points of light to help them find their way in the night sky,the astronomers used "guide craters" as points of darkness to helpthem scan the moon. "It took a lot of practice to get it all to workright," Colaprete said.

Itwas tricky for ground-basedobservatories to watch the moon, since it moves fast through the skyrelativeto the stars they normally look at. It was complicated for assets inEarthorbit as well, as they are moving very quickly themselves and are notnecessarily made to look at something so close to our planet.

"Theimpact had to be timedto within a few seconds of what the Hubble Space Telescope was doing tomaneuver to look at it," Colaprete said.

AlthoughLRO was blessed with theclosest view of the impact, the researchers had to make sure itactually didn'tget too close, arriving over the explosion 90 seconds after ithappened, orelse the debris from the explosion might have damaged it.

"Wehad to make sure allthese pieces of the puzzle were at the right place at the right time,down tothe second," Colaprete said.

Verge of failure

Onecrisis threatened to kill offthe mission entirely. Slightly more than a month before the impact, a glitchon LCROSS caused theprobe to burnmore than half of its remaining propellant.

"Thespacecraft did a littledance without our permission," Colaprete told SPACE.com. "I remembergetting a call at 4 a.m., and thinking, 'Oh, no.'"

"Itwas really scary,"he added. "At the rate it was burning fuel, if we had found out an hourortwo later, it would've been out of fuel and dead in space.Luckily, ourstellar team figured out what the problem was and how to save fuel. Wegotthere with fuel to spare."

An uncertain target

Itwas also hard to figure out whatthe best target to collide into was. Originally the researchers plannedonslamming into the crater named Cabeus A, but ultimately theychanged their mindsto nearby Cabeus crater alittle more than a week before the impact.

"Atfirst we picked thesmaller Cabeus A crater as an impact site because it was really goodforobserving from Earth," Colaprete recalled. But as they got closer andcloser and gathered more data from LRO on the way there, based on theirscansof Cabeus A for hydrogen, a signature of water, "I wasn't able toconvincemyself there was hydrogen there, so I decided to go for a certaintargetinstead," he said.

"Itwas an agonizingdecision," Colaprete said. "Not everyone was happy, since a lotwanted the ground-based observatories to have the best views theycould, but Ididn't want to impact someplace irrelevant."

Heknew he made the right decisionafter a 12-hour marathon session of combing the data after the impact."Itwas one of the most fun, giddy experiences I ever had, and we knew atthatpoint we had something really special — the data was there," he said.

Ultraviolet glows

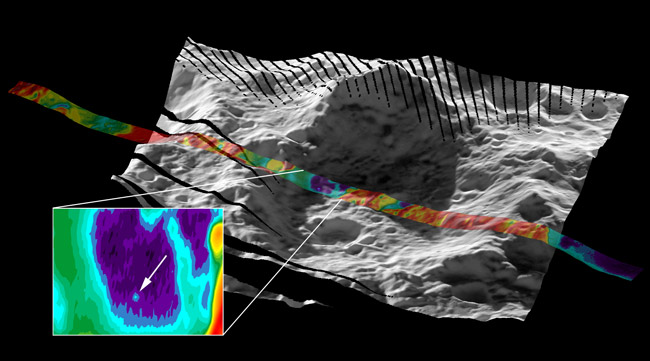

Theclosest "eyes" onhand to watch LCROSS crash was its partner, LRO, which brought a rangeofsensors to probe the results.

To identify the elements andcompounds in the debris, vaporand dust the impact kicked up, LRO employed the shoebox-size LymanAlphaMapping Project (LAMP) instrument, which looked at the crash's plume intheultraviolet range.

"Theultraviolet range iswhere a lot of materials emit and absorb, and LAMP can therefore very,verysensitively detect tiny amounts of gases," said LAMP acting principalinvestigator Randall Gladstone, a planetary scientist at the SouthwestResearchInstitute in San Antonio, Texas.

LAMP normally observes the night-sidelunar surface usinglight from nearby space and stars, which bathes all bodies in space ina softradiance known as the Lyman-alpha glow. SinceLRO wasflying over the sunlit part of the moon, which is way too bright forLAMP, thespacecraft rolled over to point the instrument at thedark sky at theedge of the visible surface of the moon instead.

LAMP detected molecular hydrogen,carbon monoxide, calcium,magnesium — and, oddly, mercury.

"Whenone of our teamsuggested it was mercury when we were just throwing out ideas, well, Isaid,'What a stupid idea, how can there be mercury there,'" Gladstonerecalled."I had to eat my words later."

Therock samples the Apollomissions brought to Earth showed heavier levels of mercury deeper down,whichled one retired scientist, George Reed, to propose that sunlight mighthavebaked the mercury out from the soil that then got trapped in craters atthesouth pole.

"Hedid a simpleback-of-the-envelope calculation and nailed it," Gladstone toldSPACE.com."If I made a great prediction like that, I'd be tickled that I wasright."

"The detection of mercury in the soilwas the biggestsurprise, especially that it's in about the same abundance as the waterdetected by LCROSS," said LAMP team member Kurt Retherford at theSouthwest Research Institute. "Its toxicity could present a challengeforhuman exploration."

These findings support the idea thatthe freezing cold ofthe permanently shadowed regions of the moon can trap vaporizedcompounds thatwafted in from deep space or other areas of the moon and preserved themtherefor eons. "They're almost literally gold mines for science," Gladstonesaid.

Heat of the impact

To see how the energy of the impactdissipated, the DivinerLunar Radiometer measured its thermal signature. They found thecollisionheated the crater floor from about minus 387 degrees F (minus 233degrees Celsius)to more than 1,250 degrees F (675 degrees Celsius), enough to turnabout 660pounds (300 kilograms) of water ice directly to vapor.

"Thecooling behavior we sawat the impact site can tell you about its physical properties," saidDiviner Lunar Radiometer teammember Paul Hayne, aplanetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology. "What wesaw was consistent with lunar soil containing the amount of ice thatLCROSSfound. The site LCROSS hit also wasn't a skating rink — it wasn't asolid blockof ice. We saw thermal emissions from there up to four hours later, andicejust doesn't do that, so ice there must have been mixed with lunarsoil."

TheDiviner instrument hadchallenges of its own, Hayne recalled.

"Wehad never used Diviner totarget a specific site on the moon," Hayne said. "Just a daybeforehand, we did a trial run to see if we could accurately target theimpactsite, and when we got our data back, we saw we were way off, so we hadtoscramble at the last minute to figure out what we did wrong. Thankfullywefixed the problem and hit it spot on. It worked out great."

Colaprete,Gladstone, Hayne andtheir colleagues detailed their latest findings in the Oct. 22 issue ofthejournal Science.

- 10Coolest New Moon Discoveries

- Video:The Last Moments of LCROSS: NASA Probe Hits Moon

- TheGreatest Lunar Crashes Ever

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us