Hot Debate Rages Over Water on Saturn’s Icy Moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

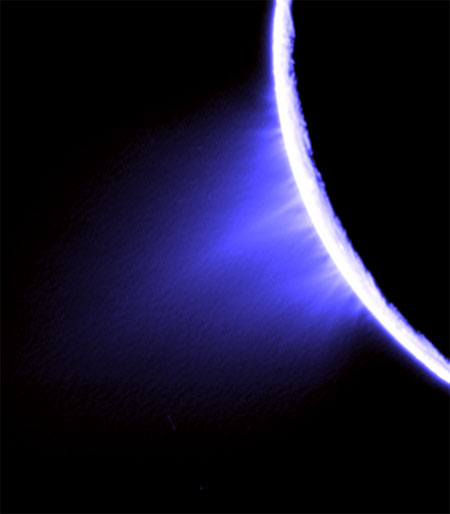

The recent discovery of plumes containing water vaporerupting from the south pole of the frigid Saturnian moon Enceladus set off afirestorm of debate.

Many scientists thought the geysersof gaseous water must boil out of liquid water stored under the moon'ssurface, which would make Enceladus a promising candidate for life.

But a new study challenges that conclusion, arguing that theplumes could just as easily come from ice through the process of sublimation -the direct leap from the solid to gaseous state.

This conclusion may dampen Enceladus' astrobiologyhopes, though it does not exclude the possibility of liquid water, and thuslife, on the moon.

Cold Faithful

Enceladus' geysers were first spotted in 2005 by NASA's Cassinispacecraft, which was launched in 1997 on a mission to orbit Saturn.Shortly after the discovery, a research group led by Carolyn Porco, head ofCassini's imaging science team, calculated the ratio of water ice to vapor inthe plumes. Cassini wasn't able to directly measure the masses of ice and vaporin the plumes, but the researchers estimated the mass of ice from the observed brightnessof the plumes (because ice reflects light, so the more ice, the brighter theplumes). They deduced the mass of water vapor from a measurement of the molecularsignature of vapor in the wavelengths of light Cassini observed from theplumes.

The scientists found that there were almost equal amounts oficeand water vapor. If this is the case, the researchers argued, the plumescannot result from the sublimation of ice.? The ice crystals are believed to bere-condensed from the vapor, rather than directly ejected from the surface orsubsurface of the moon. A lot of vapor is needed to produce that 50/50 ice andvapor ratio, but the laws of thermodynamics prevent that much vapor from beingproduced solely by sublimation. Therefore, some of the vapor must be producedby evaporation rather than sublimation.? This means a vast reserve of liquidwater must exist on Enceladus, perhaps as shallow as 23 feet (7 m) under thesurface. Under this theory, the researchers dubbed Enceladus' plumes "ColdFaithful" after the Old Faithful geyser in Yellowstone National Park. Their paper was published in 2006 in the journal Science.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But a new study led by Susan Kieffer of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign challengesthat work. She and her colleagues recalculated the ice-to-vapor ratio andproduced vastly different results. Under their calculations, vapor is much moreabundant than ice, with their final ratio less than 2:10, compared to theprevious team's estimate of 1:1.

"We simply redid the calculations described in the [previous]paper and found that we could not reproduce the results quoted for either theabundance of vapor or the abundance of ice," Kieffer said. "Ourconclusion was that sublimation should not have been excluded fromconsideration as a process that could produce the measured quantities, and thusshould be considered as thoroughly as the liquid waterhypothesis. Unfortunately, it has not been."

Kieffer and team published their findings in the May 2009issue of the journal Icarus.

Conflicting interpretations

The two contradicting conclusions paint a vastly differentpicture of Enceladus. Under the first, the moon has an icy veneer that masks adynamic region of flowing water under the surface that could possibly host life.But another interpretation sees Enceladus as a frigid world, solid with ice androck all the way through.

"Water is certainly present in Enceladus, at least as solid andvapor, but the presence of vapor does not necessarily imply that liquidwater is present," Kieffer wrote with Brucke Jakosky, a scientist at the University of Colorado in Boulder, in an essay in the June 13, 2008 issue of Science."A definitive answer about the potential for life may have to await afollow-on spacecraft mission that can make specific high-resolutionobservations that could distinguish between the competing models."

The authors of the original paper, with the more hopefuloutlook on the possibility of liquid water on the moon, agree that more work isneeded to solve the conundrum and understand the conflicting estimates of theplumes' ice-to-vapor ratio.

"Serious analysis of the Enceladus plume images areonly just beginning on the imaging team, and the jury is still very much out onthis subject," Porco said in response to the new paper.

Andrew Ingersoll, a planetary scientist at Caltech, wasinvolved with the original Porco et al. estimate, but said he doesn't believethat either ratio is truly accurate.

"Right now, I am not convinced by anyone's estimates ofthe ice/vapor ratio," he said. Ingersoll is currently working on a new,revised estimate.

Cassini is also scheduled to make future flybys of the moon,which could help refine the estimates.

"There are a number of reasons that the ice/vapor ratiocannot be used to prove or disprove either model," Kieffer said. "Nevertheless,it was the ice/vapor ratio from the original paper that gave the liquid waterhypothesis its momentum. The point of our Icarus paper is that thisvalue was miscalculated, that two competing hypotheses should have been set inmotion, and both should still be considered by the scientific community."

The intriguing possibilities and conflicting interpretationsof Enceladus are reasons why many scientists are pushing for a dedicatedspacecraft mission to the moon. Though no official plans exist, a number ofproposals are currently being considered for future NASA and ESA (EuropeanSpace Agency) missions.

- Astrobiology Top 10: Organic Brew on Enceladus

- Enceladus Evolving

- Video - Enceladus, Cold Faithful

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.