The Search for the Solar System's Lost Planet

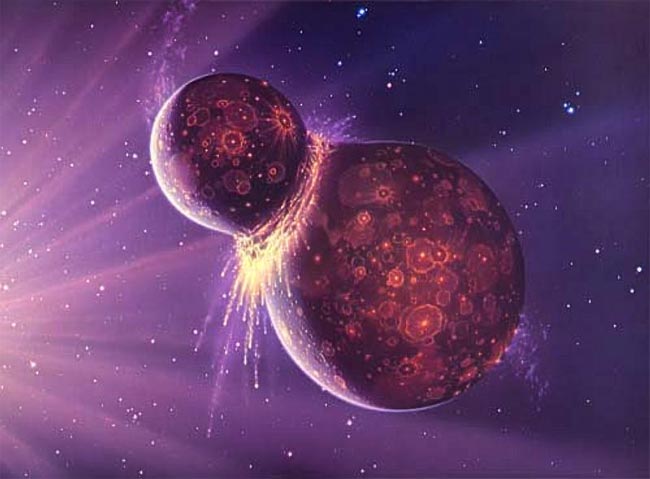

The solar system might once have had another planet namedTheia, which may have helped create our own planet's moon.

Now two spacecraft are heading out to search for leftoversfrom this rumoredsibling, which would have been destroyed when the solar system was stillyoung.

"It's a hypothetical world. We've never actually seenit, but some researchers believe it existed 4.5 billion years ago ? and that itcollided with Earth to formthe moon," said Mike Kaiser, a NASA scientist at the Goddard SpaceFlight Center in Maryland.

Theia is thought to have been about Mars-sized. If theplanet crashedinto Earth long ago, debris from the collision could have clumped togetherto form the moon. This scenario was first conceived by Princeton scientists Edward Belbruno and Richard Gott.

Many researchers now figure that indeed some large object crashedinto Earth, and the resulting debris coalesced to form the moon. It is unclearthough if that colliding object was a planet, asteroid or comet.

In any case, the debris that would have spun out from thetwo slamming bodies would have mixed together, and could explain some aspectsof the moon's geology, such as the size of the moon's core and the density andcomposition of moon rocks.

Scientists are hoping NASA's twin STEREO probes, launched in2006, will be able to discover leftover traces of Theia that may finally helpclose the case on the birth of our moon.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So far, signs of Theia have proved elusive to telescopessearching from Earth. But the STEREO spacecraft are set to enter special pointsin space, called Lagrangian points,where the gravity from the Earth and the sun combine to form wells that tend tocollect solar system detritus. [Click herefor an animation that explains Lagrangian points.]

"The STEREO probes are entering these regions of spacenow," Kaiser, a STEREO project scientist, said. "This puts us in agood position to search for Theia's asteroid-sized leftovers."

By visiting the Lagrangian points directly, STEREO will beable to hunt for Theia chunks up close. The nearest approach to the bottoms ofthe gravitational wells will come in September and October 2009.

"STEREO is a solar observatory," Kaiser said."The two probes are flanking the sun on opposite sides to gain a 3-D viewof solar activity. We just happen to be passing through the L4 and L5 Lagrangepoints en route. This is purely bonus science."

Scientists think Theia may even have formed in one of thesegravitational points of balance from the accumulation of flotsam that had builtup there.

"Computer models show that Theia could have grown largeenough to produce the moon if it formed in the L4 or L5 [Lagrangian] regions,where the balance of forces allowed enough material to accumulate," Kaisersaid. "Later, Theia would have been nudged out of L4 or L5 by theincreasing gravity of other developing planets like Venus and sent on acollision course with Earth."

- 24 Hours of Chaos: The Day The Moon Was Made

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Top 10 Cool Moon Facts

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 1:50 p.m. ET to properly credit Edward Belbruno and Richard Gott with the idea that a planet like Theia might have impacted Earth to form the moon.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.