Cometary Life Limit

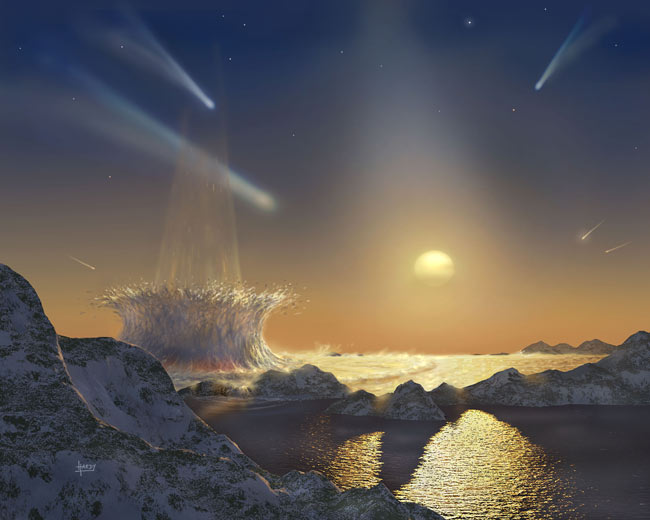

Some stars have a high level of comet activity around them,and that could spell doom for any life trying to take root on any local planets.Ongoing research is trying to determine what fraction of stellar systems may beuninhabitable due to comet impacts.

Many of our own solar system's comets are found in the KuiperBelt, a debris-filled disk that extends from Neptune's orbit (30 AU) out toalmost twice that distance. Other stars have been shown to have similar debrisdisks.

"The debris is dust and larger fragments produced bythe break-up of comets or asteroids as they collide amongst themselves,"says Jane Greaves of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.?

Roughly 20 percent of nearby sun-like stars have debris disksthat are more substantial than our Kuiper Belt, according to data from theSpitzer space telescope. More debris means more comets, but does this also meanmore killer impacts for any Earth-like planets that might be orbiting thesestars?

The answer depends on whether there are any gas giant planetsaround.

Jupiter is known to shield Earth from some comets bydeflecting them out of the solar system. However, scientists showed in 2007that Jupiter also injectsother comets into Earth-crossing orbits. In fact, if Jupiter were Saturn'ssize, the number of impacts on Earth would have been much higher.

Greaves has been modeling how comets are generally affectedby gas giants. Her early results indicate that comets will be a major problemaround a few percent of sun-like stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Comet sweep

Early in our solar system's history, there were plenty ofremnants left over from planet formation. All this debris led to a heavybombardment of comets and asteroids on the inner planets, as evident in thecrater record of the moon (on Earth, most of these scars have eroded away withtime or have disappeared due to tectonic activity).

The number of impacts eventually tapered off around 3.8billion years ago, 700 million years after the solar system formed.

The cause of this decrease may have been a shift in theorbits of the gas giants that cleared away many of the comets. Jupiter andSaturn appear to have migrated outwards, pushing out on the orbits of Uranusand Neptune. This in turn perturbed the Kuiper Belt and ejected many of thecomets into interstellar space, Greaves says.

"This might be a very peculiar event, or it mighthappen in other star systems — we don't know yet, because we have limitedinformation about their giant planets," she says.

Catastrophic impact

Still, our planet has not been completely immune to deadlyimpacts.?

Many scientists believe the dinosaurs were snuffedout by a 4-20 kilometer-wide comet or asteroid that struck 65 million yearsago at a point on the Yucatan peninsula. The impact led to a global firestormand the eventual extinction of more than half of the planet's life forms.

A 100-kilometer impactor would have left no survivors. Sucha "catastrophic impact" would destroy the entire crust of the Earthand eject the atmosphere into space.

The Earth likely experienced a few of these catastrophicimpacts very early on, before life as we know it had even begun.

"While 'dinosaur-killer' class impacts occur aboutevery 100 million years [on Earth], we would be unlikely to experience another100-km class event in the lifetime of the sun," Greaves says.

How much higher would the impact rate on a planet need to beto prevent life from ever forming?

Greaves thinks that life could not evolve on a planet where 10-100kilometer-size impactors hit every 20 million years. This kind of bombardmentdoesn't allow organisms enough time to recover between blows. The level ofbiodiversity remains low, so there's less probability that any species willsurvive the next devastating impact.

In previous work, Greaves and her colleagues speculated thatTauCeti—a nearby sun-like star that has been a favorite target of SETIsearches—is uninhabitabledue to the large number of comets that appear to be buzzing around it (althoughthis assessment may have been overly pessimistic, she now says).

Her team is currently looking at the general threat posed bycomets. They have modeled various representative planetary systems (both withand without gas giants). From this, they estimate that at least a few percentof stars are going to be too comet-stricken to be in the running as possiblehosts for life.

- Video - NASA's Dawn Asteroid Probe Revealed

- Death Down Asteroid Alley

- The Great Impact Debate

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.