Astronomers Aim to Grasp Mysterious Dark Matter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

For the past quarter century, dark matter has been a mystery we've justhad to live with. But the time may be getting close when science can finally unveilwhat this befuddling stuff is that makes up most of the matter in the universe.

Dark matter can't be seen. Nobody even knows what it is. But it must bethere, because without it galaxies would fly apart.

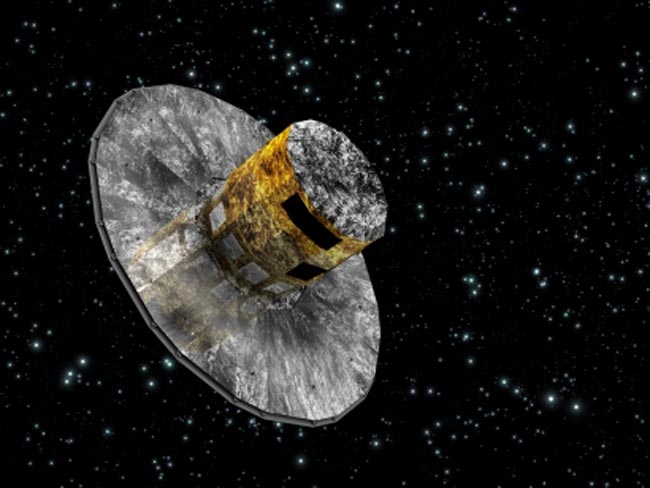

Upcoming experiments on Earth such as the LargeHadron Collider (LHC) particle accelerator in Switzerland, and a newspacecraft called Gaia set to launch in 2011, could be the key to closing thecase on one of the biggest unsolvedmysteries in science.

A disturbing truth is accepted by most astronomers: There is a lotmore stuff in the universe than what we can see. Scientists now thinkvisible matter ? all the planets, stars, and galaxies that shine down on us ?represents only about 4 percent of the mass-energy budget of the universe,while dark matter and its even more esoteric cousin, dark energy, make up therest.

"There is no consensus actually at all as to what dark matteris," said Gerard Gilmore, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge whowrote a recent essay for the Dec. 5 issue of the journal Science aboutthe search for dark matter.

A leading hypothesis posits that dark matter is composed of some kind ofexotic particle, yet to be detected, that doesn't interact with light, so wecan't see it. One such theorized class of particles is called WIMPs (Weakly interactingmassive particles), which are thought to be neutral in charge and weigh morethan 100 times the mass of a proton.

Atom smasher

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The newly-opened LHC, a 17-mile-long (27 kilometer-long) undergroundring in which sprays of protons speed around and crash into each other,could be the first experiment to detect WIMPS. The particle acceleratorofficially went online in September 2008, but was halted shortly after due to afault with its construction ? it's due to go back online in the summer of 2009.Since the LHC is the largest and most powerful atom smasher ever built, itscollisions could produce the extremely high energies needed to create theelusive particles.

In fact, the LHC will likely create a host of never-before-seen particles,opening up a realm of the universe that physicists have been eager to explore.

"The assumption is, there will be whole families of new types ofparticles," Gilmore said in a podcast interview with a reporter from Science."The challenge then is to say, well OK, we now then have a new set ofingredients in our recipe for how nature is put together, but what is therecipe that uses this set of ingredients? I.e., what mix of these particlesdoes nature actually use to create the universe, and how?"

Weighing the universe

That's where Gaia comes in. The European Space Agency satellite isdesigned to measure positions and speeds of about 1 billion nearby stars withunprecedented precision. Its vision is so sharp it should be able to discernthe equivalent of a shirt button on the surface of the moon as seen from Earth,Gilmore said.

By establishing where things are in our galaxy, the spacecraft will helpscientists measure the weight and distribution of mass in the Milky Way in muchgreater detail than ever before. These measurements are vital for models thatattempt to describe how the pull of dark matter has shaped our galaxy.

"What Gaia will do is measure the distances of stuff and measurehow they're moving in three dimensions around space to much better precisionthan we've had before, which will allow us to weigh things on all sorts of scalesdown to the smallest scales we can find," Gilmore said. "They willtell us to exquisite precision how the dark matter is distributed in space,which is the recipe we need to determine its properties."

- Vote: Strangest Things inSpace

- Images:Hubble's Views of the Universe

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.