NASA's Final 4 Shuttle Flights Vital for Space Station

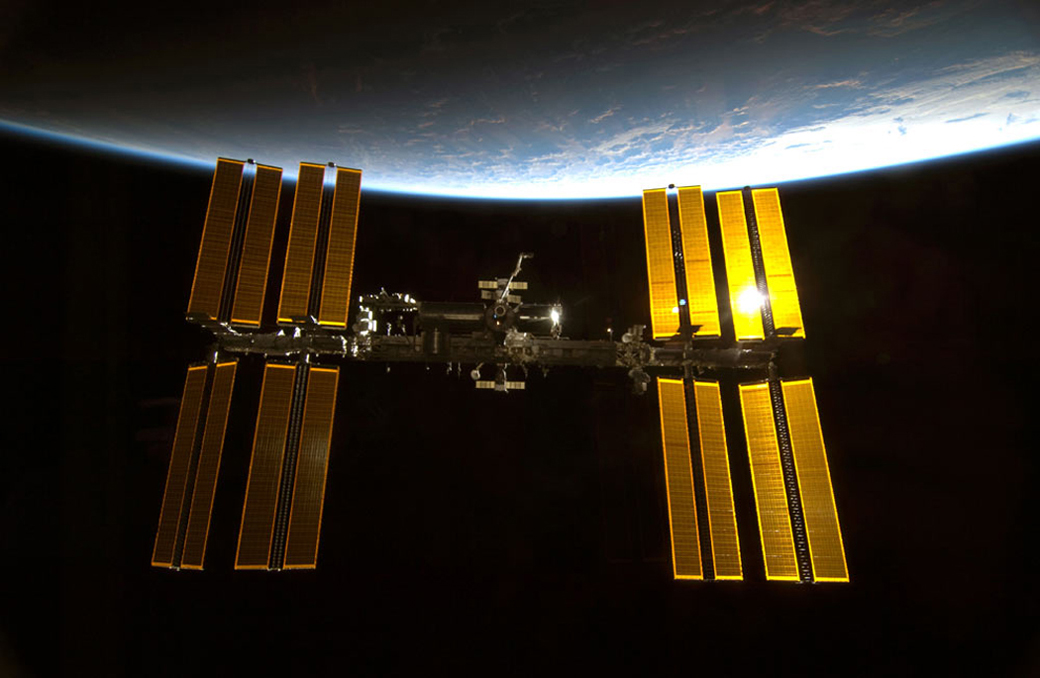

CAPE CANAVERAL ? With the International Space Stationnearly complete, the final four shuttle missions hope to ensure it's built tolast.

After the shuttle'sretirement, a fleet of smaller vehicles -- including two that have flownonce and two more that have never flown -- will be counted on to bring up thefood and equipment needed to ensure the $100 billion research outpost stays inservice for at least another decade.

To give thestation the best chance to sustain a failure or late deliveries, NASA is stockingit with large spare parts only flown easily by the shuttle and asmuch food and other goods as possible.

"We'vedone as good as we can with the remaining shuttle flights," said BillGerstenmaier, NASA's associate administrator for space operations. "We'veoptimized things, we've put things in place, and we're really kind of set up asgood as we can (be)."

Theshuttle's work resumes with Monday's 6:21 a.m. blastoff from Kennedy SpaceCenter of Discoveryand seven astronauts. Their 13-day mission will haul up more than 17,000pounds of equipment and supplies and a large coolant tank.

Change ofplans

The spacestation, which extends the length of a football field and weighs about 800,000pounds, began construction in 1998 with the shuttle's cargo capacity in mind.But plans changed after the 2003Columbia disaster. President George W. Bush announced plans to retire theshuttle in 2010, a timeline that President Barack Obama has stuck to.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA beganto carefully analyze which station parts were most likely to fail andprioritize the delivery of spares best carried up by the shuttle.

Thatplanning has taken on more importance, with Congress expected to extend thestation's life by five years, to 2020 to further capitalize on the hugeinvestment of time and money that went into building the outpost.

"It'scritical that all these missions go off successfully for the long-termsustainment of the station," said Cristina Chaplain, director ofacquisition and sourcing management for the U.S. Government AccountabilityOffice. "After the shuttle retires, there will be no comparable vehiclethat can take things of the size and weight that the space shuttle cantake."

?Spareparts

The bulky,1,800-pound ammonia tank flown by Discovery is an example of the large partsvital to the station's long-term survival.

AstronautsRick Mastracchio and Clay Anderson will replace an existing tank over thecourse of three spacewalks, replenishing a system that helps dissipate heatgenerated by the station's electrical systems.

Othercritical parts include dome-shaped gyroscopes, doghouse-sized gas tanks andradiator panels that extend 75 feet.

It's easy totransport bunches of them in the shuttle, which can launch a maximum weightequivalent to two 71-passenger buses driven by Brevard Public Schools. One ofthose buses could fit in an orbiter's 60-foot payload bay.

But if theshuttle has served as a space truck over the years, its successors are morelike vans, wagons or -- in the case of the RussianSoyuz capsule that American astronauts will ride to the station until a newU.S. crew vehicle is ready -- a hatchback.

NASA willrely on five unmanned spacecraft to deliver cargo to the station, includingvehicles flown by three international partners. European and Japanesefreighters that have less than half the shuttle's capacity have each flown onceand are only expected to fly once a year. Russia's more compact and provenProgress spacecraft will make six deliveries this year.

But over thenext five years, plans call for more than half of the 182,000 pounds of drycargo the outpost is expected to need to be carried by spacecraft indevelopment by U.S. companies SpaceX and Orbital Sciences Corp., according to a2009 GAO report.

SpaceX'sDragon will lead the way, with resupply runs targeted for next May andOctober. But first the new spacecraft must successfully complete threedemonstration flights, planned to start in July.

Thattimeline appears challenging since the company's Falcon 9 rocket has not yetflown. The inaugural launch could happen next month from Cape Canaveral.

Orbital'sTaurus II rocket and Cygnusspacecraft are preparing for a single demonstration flight next March, withlater flight dates still to be determined.

?Sense of urgency

"We've always felt there was risk inthat (commercial cargo) schedule, by virtue of inherent complexities indeveloping new rockets and new spacecraft," Chaplain said. "I thinkthose stand."

To reduce that risk, NASA's 2011 budgetproposal requests $312 million to bolster the demonstration program withadditional tests -- a 62 percent increase over the $500 million originallyallocated.

"Anytime you can add more testing to theprogram, that increases your probability of mission success," said AlanLindenmoyer, manager of NASA's Commercial Crew and Cargo Program Office.

The flights' urgency depends in part on howwell station systems hold up.

If all goes well, Gerstenmaier said acommercial delivery could slip into late 2011 or early 2012 before suppliesmight begin to run low, threatening the station's ability to sustain a fullcrew of six.

"Beyond that, it becomes moreproblematic, depending on what fails," he said. "We need those folksas soon as they're ready to fly."

Their performance will be watched even moreclosely now that Obama wants to turn the transportation of U.S. astronauts overto commercial companies, too.

Back to earth

The Dragonflights also are seen as critical to the station's science goals.

It's the only spacecraft planned after theshuttle that can return a significant quantity of cargo to the ground, acapability called "downmass" that is critical to some scientists whoneed experiment samples returned for further study.

Discovery, for example, will bring home 72glass vials holding jatropha curcas plants that Wagner Vendrame, an associateprofessor at the University of Florida in Homestead, hopes may be commerciallycultivated as an alternative energy crop.

"In order to finalize the experiment andcollect the results of what we're performing, we need to do certain analysisthat we would not be able to do in space," he said.

David Watson, interim associate director ofthe National Space Biomedical Research Institute in Texas, said technologyimprovements such as video monitoring are helping investigators collect dataremotely and reduce the quantity of samples needing return.

Prospective station researchers also knowthat proposals to fly and return large equipment are less likely to winapproval.

"Considering all the experiments thatcould be sent up there, those with less constraints probably have a betterchance, because you don't have to bump something else to get a piece ofequipment there or to return samples," he said.

NASA scientists are confident the stationwill flourish as a unique platform for microgravity research. BeforeEndeavour's February launch, Julie Robinson, the station program scientist,called the post-shuttle transportation plan "very robust."

"We have no concerns about being able tobring home samples for investigators over the life of this extended spacestation," she said.

- Images:Spotting Spaceships From Earth

- NASA?sMost Memorable Missions

- FinalCountdown: A Guide to NASA's Last Space Shuttle Missions

- RareTwilight Shuttle Launch on Monday Visible to U.S. East Coast

Publishedunder license from FLORIDA TODAY. Copyright ? 2010 FLORIDA TODAY. No portion ofthis material may be reproduced in any way without the written consent of FLORIDA TODAY.

James Dean is a former space reporter at Florida Today, covering Florida's Space Coast through 2019. His writing for Space.com, from 2008 to 2011, mainly concerned NASA shuttle launches, but more recently at Florida Today he has covered SpaceX, NASA's Delta IV rocket, and the Israeli moon lander Beresheet.