Premier Cosmic Catalogue Updated

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The best 3-D map of the cosmos just got better, thanks toan astronomer's years of cleaning up old satellite data.

The fresh look at almost 118,000 stellar bodies, known asthe Hipparcos catalogue, boosts the astrometric database's accuracy by up tofive times and effectively doubles its useful information.

"This catalogue provides extremely fundamental,direct measurements in astronomy, such as distances, masses and kinematics ofstars and star clusters," said Floor van Leeuwen, an astronomer at the Institute of Astronomy at University of Cambridge in the U.K. who single-handedly filtered the data.

Van Leeuwen's updated version of the catalogue isdetailed in part of a new book called "Hipparcos - The New Reduction ofthe Raw Data."

Star-crossed satellite

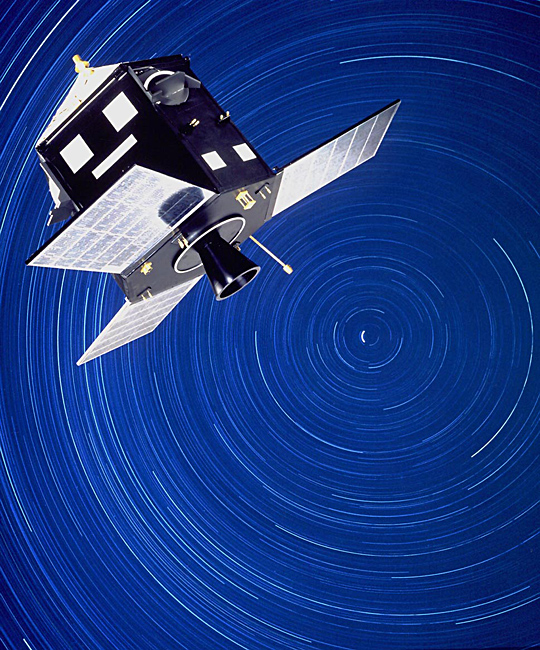

In 1989,the European Space Agency (ESA) launched Hipparcos—the High Precision ParallaxCollecting Satellite—to map out some of the brightest stars and star clustersin the cosmos.

Van Leeuwensaid the satellite's data may be old, but its accuracy is still impressive."If the satellite was on Earth, it would be able to see a child on themoon take a step," van Leeuwen told SPACE.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thesatellite scanned the sky in two directions for 4 years, allowing astronomers tocalculate the distancefrom Earth to each stellar object by using the parallax method-or observingan object from two points in space, when Earth is in different points on itsorbit around the sun. Our brains, for example, use the same principle to mergeinformation from two eyes to give us depth perception.

"You'reessentially triangulating the entire sky," he said of computing Hipparcos'data. Complicating the extremely precise calculations, however, was thesatellite's off-kilter orbit around Earth caused by a failed rocket.

Van Leeuwensaid comparing both data sets amounts to a dizzying amountprocessing—especially with errorspresent.

Nastynumber crunching

Red flagsin the catalogue-such as a 10 percent difference in calculated distance to thePleiades star cluster-set astronomers off to the errors, but they struggled tounderstand them. Scientists eventually showed that fast-moving dust grainswhacking into the spacecraft could vibrate it and throw off measurements."Pings" in satellite material caused by solar heating andcontraction, similar to the sounds made by a cooling car engine, were also isolated.

With theinformation in hand, van Leeuwen decided to sit down at his computer andpainstakingly filter through the 118,000 data points, then re-crunch thenumbers.

"Ittook me about two-and-a-half years in total, and I found about 1,600 of theseevents," he said. "When I took the events out of the data, theaccuracy increased by a factor of five."

Van Leeuwensaid his personal computer took about three to four weeks to process oneiteration, or "rough draft," of the cleaned-up stellar map-and 15total iterations were needed to create the complete final draft. But the newversion, he said, should help astronomers better understand the motions of thecosmos as well as inform the designof Gaia-the next-generation astrometric satellite.

The ESAexpects Gaia to observe about 1 billion stellar objects, or about 8,300 timesmore than Hipparcos did in the early 1990s.

"It'sabsolutely frightening to think about the data that will be coming down fromGaia," van Leeuwen said of the satellite, which is scheduled to launch in2011. "The world's best computers currently can't handle that kind ofdata, so we hope we'll be able to in about 5 years' time."

- Video: Our Corner of the Cosmos

- The Strangest Things in Space

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.