Star System Soaked With 'Rain'

NASA'sSpitzer Space Telescope has revealed a dusty star system being soaked with a"steamy rain" of water vapor.

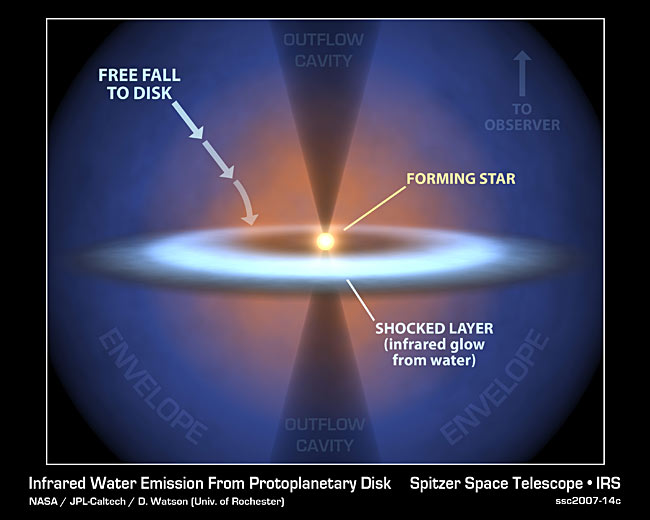

The water,pulled from gassy stellar leftovers into a dusty disk, provides whatastronomers think is the first direct look at how the life-giving liquid makesits way into planets. The disk is the same sort of thing that forms around manystars and, in the case of our sun, was the seedbed for planet formation.

The amountof water in the newly observed disk is thought to equal more than five timesthat of all oceans on Earth.

"Forthe first time, we are seeing water being delivered to the regionwhere planets will most likely form," said Dan Watson, anastrophysicist at the University of Rochester in New York.

Watson andhis colleagues' work will be detailed in the Aug. 30 issue of the journal Nature.

Steamysurprise

Water isabundant throughout our universe, existing as ice or gas around stars and inthe space between stars, but rarely as a liquid.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"OnEarth, water arrived in the form of icy asteroids and comets," Watsonsaid. "Water also exists mostly as ice in the dense clouds that formstars."

Astronomersfound the watery evidence in a young star system called NGC 1333-IRAS 4B, located1,000 light-years away in the constellation Perseus. The system still growsinside a cooled cocoon of gas and dust, and Spitzer data show that ice isfalling from the cocoon into a warm disk of potential planet-formingmaterials circling the star.

As the icesmacks into the dust, it vaporizes.

"Nowwe've seen that water, falling as ice from a young star system's envelope toits disk, actually vaporizes on arrival," Watson said. "This watervapor will later freeze again into asteroids and comets."

Drysearch

Watson andhis team's discovery comes after a detailed look at 30 similarly young starsystems with Spitzer's infrared spectrograph, an instrument that reveals"fingerprints" of molecules like water. Of the 30 stellar embryosinvestigated, only NGC 1333-IRAS 4B harbors significant amounts of water.

The drysearch, however, may not be due to a lack of water in the other star systems,the astronomers explained. NGC 1333-IRAS 4B is in just the right orientationfor Spitzer to view its dense core and, they added, such a watery phase isshort-lived and hard to catch.

"Wehave captured a unique phase of a young star's evolution, when the stuff of lifeis moving dynamically into an environment whereplanets could form," said Michael Werner, a project scientist with theSpitzer mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Theastronomers explained that water serves as an important tool for studying the planetformation process, which is not very well understood.

"Wateris easier to detect than other molecules, so we can use it as a probe to lookat more brand-new disks and study their physics and chemistry," saidWatson. "This will teach us a lot about howplanets form."

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- VIDEO: Looking for Life in All the Right Places

- Water Found in Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.