Eta Aquarid Meteor Shower 2018 Is Peaking Now! Here's What to Expect

Interestingly, all of the major meteor showers occurring from April through October this year happen on a weekend. This may make it easier for you to look for "shooting stars" during the predawn hours without having to worry about getting up for work or school later that morning.

Just before daybreak on Sunday (May 6), for instance, is the peak of the Eta Aquarid meteor shower. This meteor display is active in the first week of May and produces long streaks whose paths are aimed away from the "water jar" of Aquarius. Their streaks are long for a good reason, for which I will explain in a moment.

But to curb your enthusiasm, I feel it necessary to also tell you that this year, the Eta Aquarids will be poorly seen, because of glare from a waning gibbous moon, which turned full on April 29. Although not as bright (66-percent illuminated) as when it was full, it will still serve to light up the morning sky and likely squelch most of the fainter streaks from being visible. In other years — without a bright moon — the Eta Aquarids are usually the richest meteor display for observers in the Southern Hemisphere, producing up to 60 meteors per hour. [Eta Aquarid Meteor Shower 2018: When, Where & How to See It]

Too low

Bright moonlight is only one of two obstacles to viewing this shower. The other problem is that if you live north of the equator, hourly meteor rates drop off rather rapidly. [A Gift from Halley's Comet: The Eta Aquarid Meteor Shower in Photos]

This is especially true for north temperate latitudes because the Eta Aquarid radiant, from which the meteors appear to dart, never reaches a high altitude above the southeast horizon. It rises around 3 a.m. local daylight time, so rates are correspondingly low.

Observers typically report only 10 meteors per hour at 26 degrees north, or about the same latitude as the Florida Keys. A little farther north at 35 degrees latitude (or the southern border of Tennessee), viewers may see about five meteors per hour. Beyond the 40th parallel north—a line of latitude that lies on the Kansas and Nebraska—skywatchers will see little to no meteors.

Hope for a "grazer"

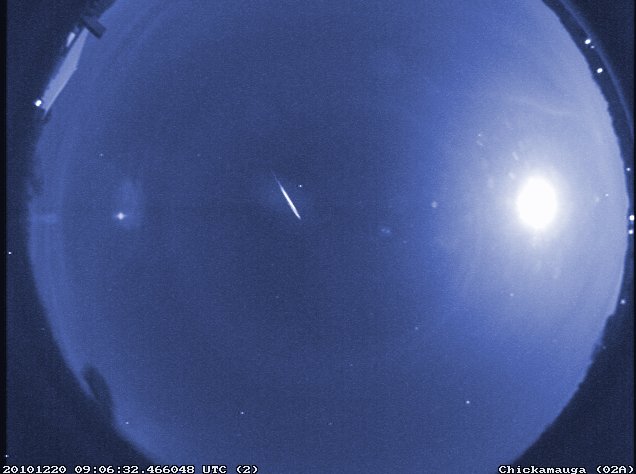

Even if you live in a far northern location, there is still reason to head outside and take a look, for it is possible that you just might luck out and spot an "Earth grazer." These are meteorsemerging from the Aquarid radiant that will skim the atmosphere horizontally — much like a bug skimming the side window of an automobile. They also sometimes leave colorful, long-lasting trails.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Remember the long Aquarid trails? Well, Earth-grazing meteors tend to be extremely long and usually appear to hug the horizon rather than shooting overhead, where most night-sky photographers aim their cameras.

"Earth grazers are rarely numerous," cautioned Bill Cooke, a member of the Space Environments team at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. "But even if you only see a few, you're likely to remember them."

Halley's legacy

And if for nothing else, be aware that if you catch sight of an Aquarid meteor, you will have seen a piece of space debris that was shed by the famous Halley's Comet in past centuries. They remain traveling more or less along the comet's 75-year orbit around the sun. The particles likely range in size from sand grains to pebbles, and they have the consistency of cigar ash.

Earth, in its annual orbit around the sun, passes through this thin "river of rubble" twice: once in late October, producing the annual Orionid meteor shower, and also in early May, causing the Eta Aquarids. Each meteoroid collides with Earth's upper atmosphere at 41 miles per second (66 kilometers per second), creating an incandescent trail of shocked, ionized air. This hot trail, not the tiny meteoroid itself, is what you see.

And in case you're wondering, Halley's Comet itself will return to the sun's vicinity in the summer of 2061.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon Fios1 News, based in Rye Brook, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.