How to See Jupiter by Day and its Moons by Night using Mobile Astronomy Apps

Jupiter is perfectly positioned for observing this spring. As darkness falls the planet is already shining brightly in the southeastern evening sky. It crosses the sky over the course of the night and sets in the west just before dawn. And you don't have to wait for it to become fully dark before observing it — the planet is bright enough to find in twilight. It's even possible to see Jupiter in broad daylight, if you know where to look.

At night, binoculars will reveal Jupiter's four largest moons waltzing around Jupiter on predictable schedules, sometimes gathering to one side or the other, and occasionally disappearing from view. A small telescope will show them more clearly, and also reveal the brown belts that make the planet look striped. A bigger telescope will let you see the Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years. When the geometry is just right, Jupiter's moons cast small black shadows while they cross the planet. You can see them, too, with a medium or large telescope.

In this edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll tell you how to use apps to identify Jupiter, see the motions of its moons, find out when the Great Red Spot and moon shadows are visible, and even see Jupiter in the daytime! [Jupiter is a Feast for the Eyes In New Time-Lapse Animation (Video)]

Finding Jupiter

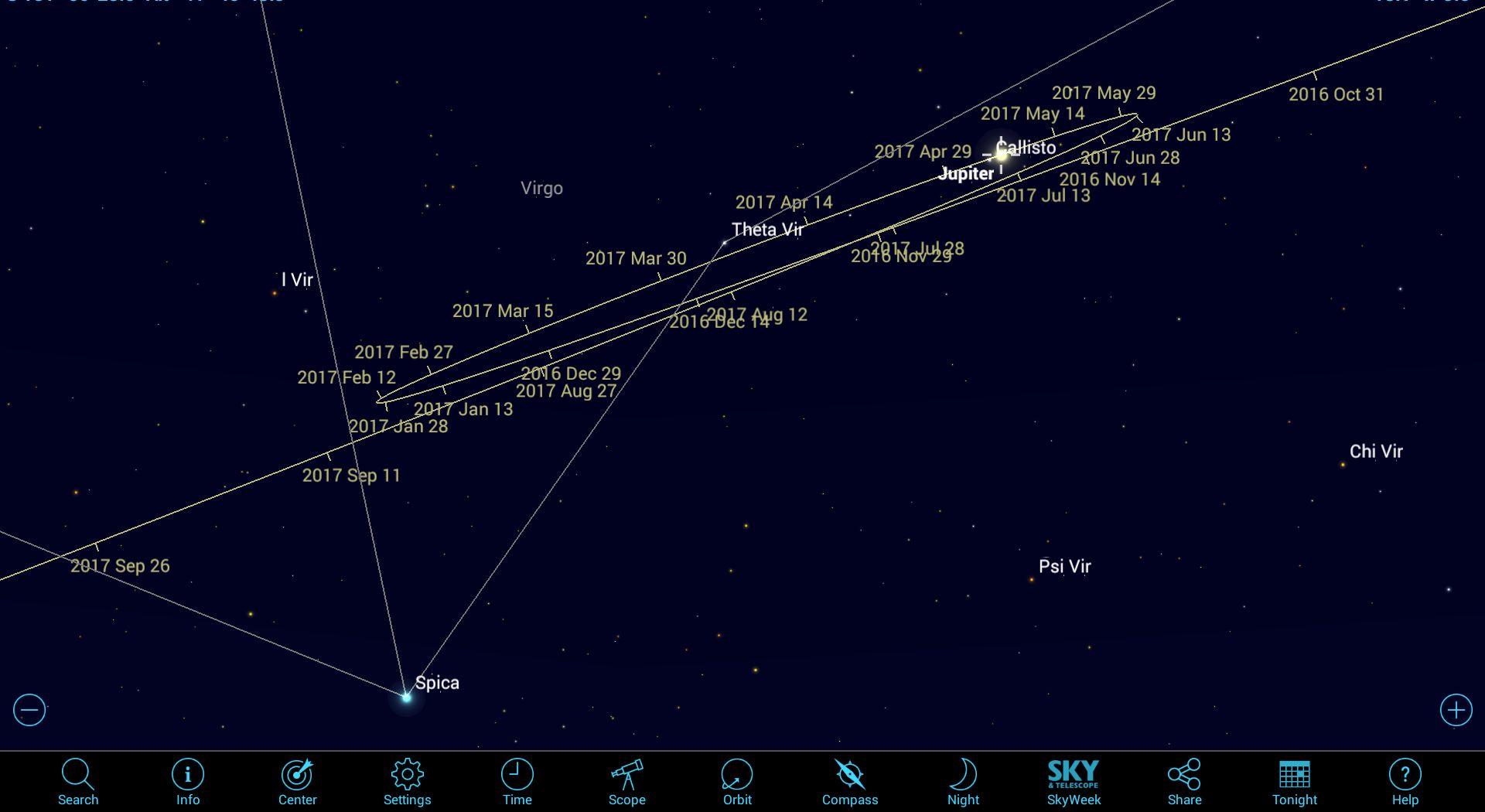

In May 2017, Jupiter is sitting in the southeastern evening sky, within the constellation of Virgo. Virgo's brightest star, Spica, is about 10 degrees (an outstretched fist's diameter) below Jupiter. It's easy to tell the planet from the star. Despite Jupiter's great distance, its large globe reflects a lot of sunlight: it's second only to Venus in brightness among the planets, and it outshines every star in the night sky. By the time Jupiter sets in the west before dawn, the rotation of the sky has moved Spica upward to the left of the planet.

Jupiter will be visible in evenings for the next few months. But try to look now, while the planet is higher in the sky and shining through a thinner layer of the Earth's distorting atmosphere. By August, the planet will be sinking into the western twilight after sunset and shining through twice as much atmosphere. After mid-September, due to Earth's orbital motion, Jupiter will disappear from view while it's near the sun during solar conjuction, and then become a morning object at year-end.

Spotting the Great Red Spot

The famous Great Red Spot (or GRS) on Jupiter is a cyclonic storm that has been raging on Jupiter for at least 185 years. A persistent spot on Jupiter was reported even earlier, by Giovanni Cassini, from 1665 to 1713 — but no one is sure whether that was the same storm we see today. The Great Red Spot's oval is large enough to hold two to three, and it is visible in backyard telescopes. Jupiter rotates quite quickly — once on its axis every 10 hours — and the spot takes about 3 hours to traverse the planet's disk. Thus, the spot is not visible every night. A mobile astronomy app is a perfect way to find out when to see it.

Many sky-charting apps show Jupiter as a photographic image with the red spot visible, which might fool you into thinking it's always there. However, the better apps such as SkySafari 5 present Jupiter as a complete globe that rotates at the correct rate. If your app is set to the current time, it will show Jupiter as it appears in your telescope right now. But there's a catch. Jupiter is far enough away (more than 424 million miles, or 682 million kilometers) that we don't see events there in real time. The light needs time to travel all the way to Earth. It varies through the year, but right now, it's delayed by about 37 minutes. The SkySafari app has an algorithm that corrects for this, but some of the other sky-charting apps I tested did not.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another option is to choose an app that focuses exclusively on Jupiter. Sky & Telescope Magazine has a very good app for iOS users called JupiterMoons (developed by the SkySafari app team). It allows you to view the planet's current appearance and move forward and backward in time, in increments ranging from seconds to years. A separate page provides a list of upcoming GRS transits in local time, and another offers plenty of Jupiter facts and figures. The CalSKY website generates tables of GRS transits visible at your location, and plenty of additional information for Jupiter and the other planets.

The dance of Galileo's moons

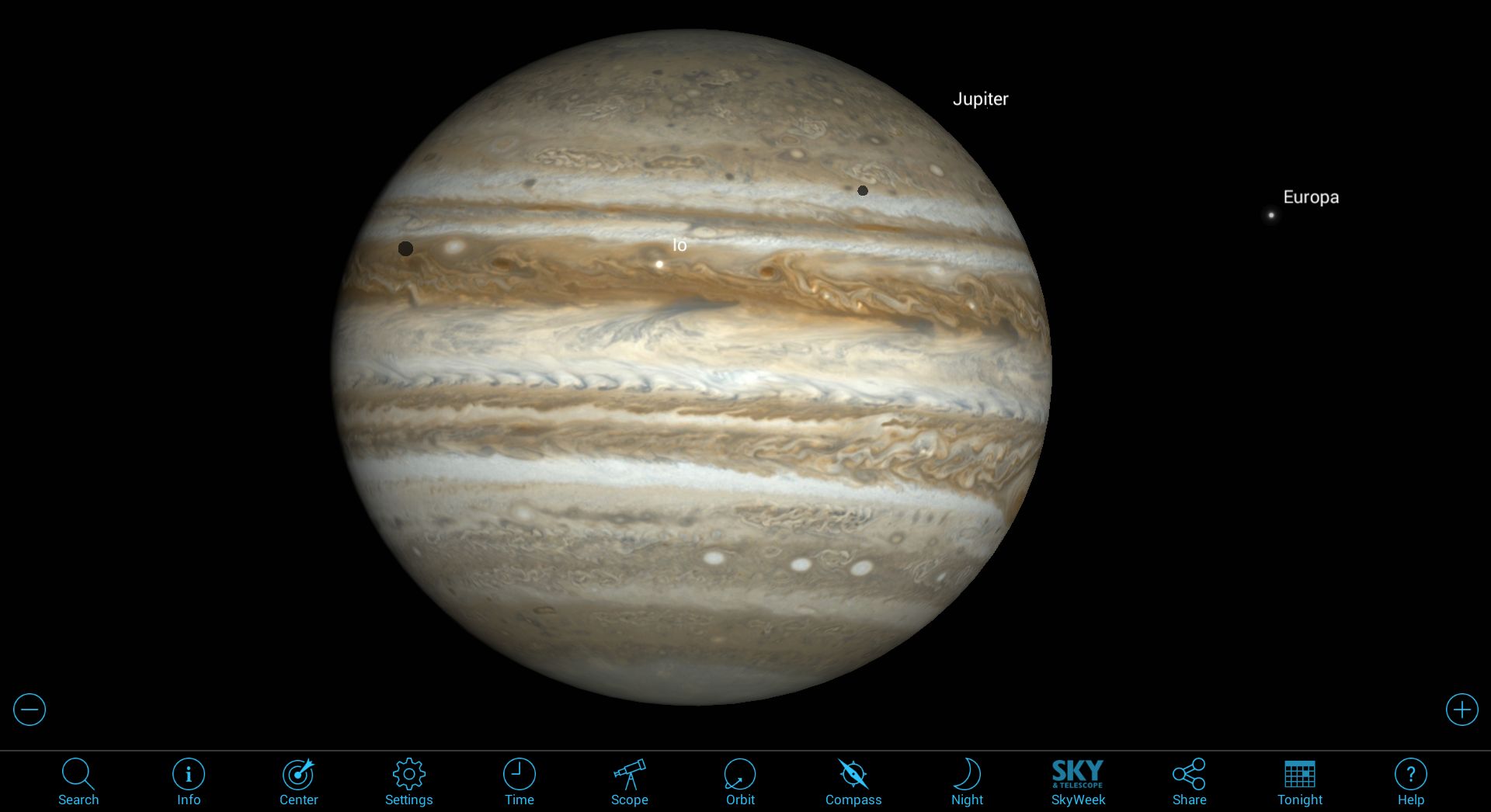

Jupiter has more than 60 natural satellites, or moons — many are small objects that have been trapped by the massive planet's gravity. The four largest moons were first observed by Galileo Galilei in 1609 using a very modest telescope. By observing the moons nightly over a period of weeks, he discovered that they were orbiting Jupiter — a controversial statement in his day. Astronomers commonly refer to the big four as the Galilean moons. From closest to farthest from Jupiter, they are named Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Io is closest to its planet and moves faster than the outer ones, needing only 1.8 days to orbit Jupiter, while distant Callisto takes nearly 17 days. [Photos: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter]

Even modern-day binoculars are better than Galileo's little spyglass, so you can look for the moons yourself. Unlike the Earth's axis, which is tilted with respect to the plane of the solar system, Jupiter's axis is vertical, so the Galilean moons always appear along a straight line that runs parallel to the planet's equator. Their differing orbital speeds produce different arrangements of the moons: close together, well separated, arranged symmetrically and sometimes all clumped to the left or right (east or west) side of Jupiter. This makes it fun to check in on them from time to time. The Jupiter system runs like clockwork, so we can accurately predict events far into the future. Your app will tell you which ones are visible where you live.

It takes only a short while to notice the moons shifting in position. Your sky-charting app will have at least the four Galilean moons labeled, and perhaps some additional fainter ones. For iOS users, the Jupiter Guide app, the Gas Giants app and the Sky & Telescope app noted above all show a clear view of the arrangement of the planet and the moons, and offer a slider or buttons to alter the time. Android users should check out the Jupiter Simulator app. Unlike binoculars, most telescopes will invert or mirror image your view of Jupiter. Some of the apps allow you to select the mode that matches your equipment. Because the moons seldom line up symmetrically, it's simple to compare what you are observing in your eyepiece with the app, and configure the flip buttons until it's the same.

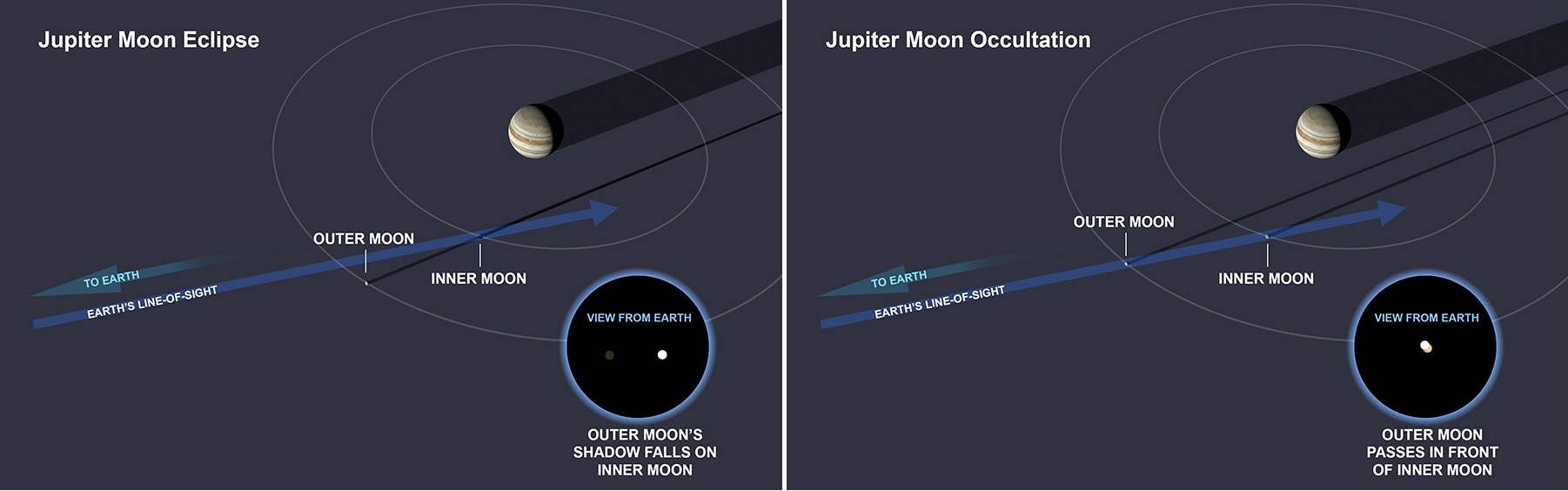

Our line of sight to Jupiter also means that the moons can transit (or cross) the planet; disappear or emerge from behind it (called occultations); or even pass in front of one another. Just as our moon is eclipsed when it passes through Earth's shadow, Jupiter's moons can blink off and on as they enter and depart its shadow. Depending on the geometry of Earth, Jupiter and the sun, the appearances and disappearances happen well away from the edge of Jupiter. They only take a few minutes, so they are great events to watch through a backyard telescope.

While the moons themselves are difficult to see while transiting Jupiter, their little round, black shadows are easy to see in a decent telescope. You just need to know when to look. The moons and their shadows take hours to cross Jupiter. Transits near Jupiter's equator last up to 3 hours, while high-latitude events are shorter. Use the app to find out the start and end time for each event. Remember that your telescope may flip or invert the view that the app shows. Other than SkySafari 5, most of the above apps will not show you the shadows on the planet, but if your app says that a moon is transiting, it's worth looking for a shadow. When planning to observe, you can run the time forward on the app to discover when the other types of events will be occurring. [Jupiter Quiz: Test Your Jovian Smarts]

If you tap the Info icon in SkySafari 5, it will present a list of upcoming Jupiter moon and Great Red Spot events, complete with quick links that show how they will look. Just tap the clock icon and then zoom the display to see Jupiter's disk and the moons.

On very special occasions, two or even three shadows can be transiting at the same time! These are worth setting the alarm for. On Thursday (May 11), starting at 9:59 p.m. EDT (0159 on May 12 GMT), Europa and Io will both have shadows on Jupiter for about 6 minutes. Europa's shadow will already be transiting as the sky darkens. And after the double-shadow event, Io's shadow will continue alone until midnight EDT.

On May 18, starting at 11:53 p.m. EDT (or 0353 on May 19 GMT), the shadows of Europa and Io cross again, this time for 49 minutes.

On May 26, at 1:47 a.m. EDT (0547 GMT), the same pair of shadows will cross for 72 minutes, but Jupiter will be very low in the western sky for observers in the Eastern time zone.

There are online resources to track Jupiter phenomena, too. Los Angeles' Griffith Observatory provides a list of the Jupiter moon events on this page. The events and times are provided for the Pacific Time zone, but you can add or subtract the appropriate number of hours to correct for your own time zone. If you don't live in the Pacific Time zone, some of the events listed will not be visible — for instance, if the sun has not yet set, or if Jupiter has already set where you live. Conversely, some additional events will be visible only in your time zone. (This is the advantage of using a mobile app tied to your location.)

Spot Jupiter in the daytime

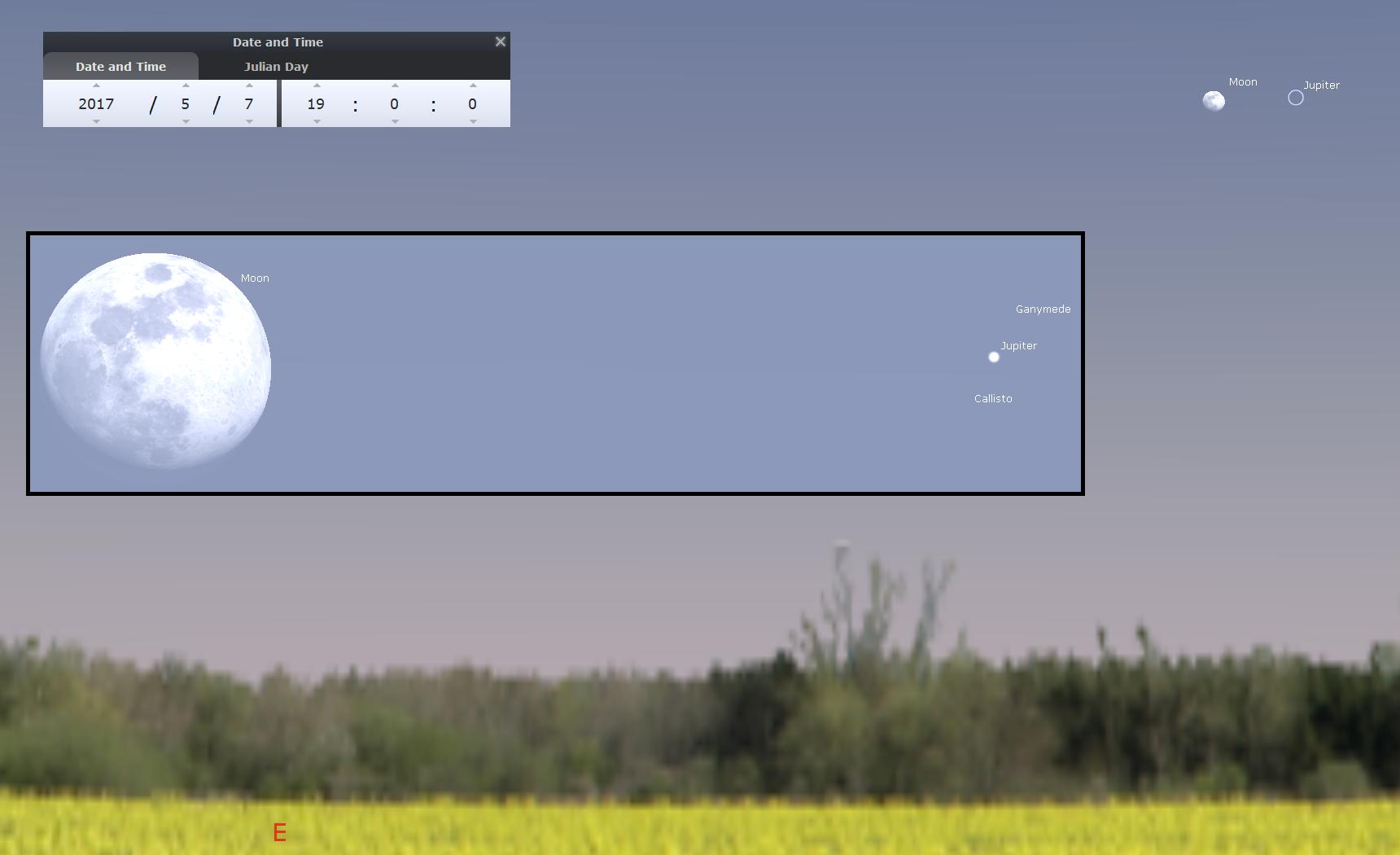

Jupiter is easily bright enough to see in broad daylight, if you know where to look. Fortunately, the moon passes Jupiter every month, and often sits close enough to make spotting Jupiter fairly easy. To the naked eye, the planet is a bright pinprick of light, but binoculars or a telescope will reveal it as a small pale disk. This month it is rising at 5:30 p.m. local time, only 3 hours before sunset. But you can use the method I give below any time the planet is well separated from the sun. Make a point of trying it this summer and fall, when it's high in the sky during the afternoon. Remember: Never point binoculars or a telescope anywhere near the sun.

Below is a list of upcoming dates when the moon is close to Jupiter. Set your app to show the date indicated and center the view on the moon or Jupiter. Alter the time to see when they are close together, and also fairly high in the sky. Zoom in on the app's display so that the moon is large enough for you to estimate how many moon diameters apart they are. Finally, make note of what direction you will need to scan — starting on the moon and moving toward Jupiter. Once you're outside, bring the moon into sharp focus in your binoculars, and then search in the correct direction, hopping by the number of moon diameters you noted. Try these dates:

On May 7, the waxing full moon is about 3.5 moon diameters from Jupiter.

On June 3, the waxing gibbous moon is about 3 moon diameters from Jupiter.

On July 28, the waxing crescent moon is about 4 moon diameters from Jupiter.

On Dec. 14, the waning crescent moon is about 6 moon diameters from Jupiter.

When the moon isn't available, you can try enabling your device's gyro and compass sensors and use the app to show you where in the sky to scan for Jupiter. It's harder — but doable. Venus is also observable using the same methods.

In future columns, we'll tour the southern skies not visible from the Northern Hemisphere, suggest some spring binocular objects, talk about galaxy types and more. Until next time — keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist, and operator of the historic 1.88 meter David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach Chris Vaughan via email, and follow him on Twitter @astrogeoguy, as well as Facebook and Tumblr.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.