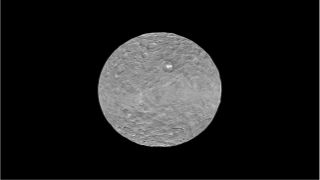

The Mystery of Dwarf Planet Ceres' Missing Craters

HONOLULU — Planetary scientists have a new mystery to investigate: Ceres, a dwarf planet that orbits the sun between Mars and Jupiter, appears to have significantly fewer craters on its surface than scientists had expected.

Meteorites that crash into the surface of planets and other bodies in the solar system usually leave behind carved-out pockmarks as evidence of the collisions. Older bodies tend to accumulate more craters than young bodies, and scientists can use their estimates of Ceres' age to calculate the number of craters that should be littered across its surface.

But the count has come up short, said Simone Marchi, a researcher at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Images of Ceres' surface taken by NASA's Dawn spacecraft have provided scientists with an initial crater count, which Marchi said is only one-tenth what models predict it should be. [7 Strange Facts About Dwarf Planet Ceres]

"There is a story there — what it is, exactly, needs to be seen," said Marchi, who is a member of the Dawn science team. He delivered his results here at the International Astronomical Union meeting, and showed the first crater maps of Ceres' surface.

"It's still an early stage for the analysis in the sense that we need to improve the crater catalog," he told Space.com.

Dawn is currently descending into an orbit much closer to Ceres' surface, where it will take higher-resolution images that will reveal smaller craters. Three-dimensional studies of the surface of Ceres may also reveal evidence of very old or very large craters that are not immediately recognizable in two-dimensional images.

But even those additional craters won't fill in the missing 90 percent.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I don't think we will find a factor of 10 more craters," Marchi said. "Although the crater catalog is still preliminary, I think it's in good shape for large crater size — say, larger than 20 kilometers [12 miles]."

The model used to make the initial prediction of about how many meteorites should have crashed into Ceres in its lifetime is a "standard baseline," Marchi said, noting that more work will be done to "check the modeling and tweak parameters and see what we can get from that."

It's possible that these models need improvement, but there are also many ways that evidence of meteorite impacts could have been erased over Ceres' lifetime, he added.

Geological activity, such as earthquakes and volcanoes, can erase the presence of craters. But Ceres doesn't appear to have volcanoes, and Marchi said scientists have no strong evidence to suggest that the dwarf planet is (or ever was) geologically active. (Scientists were surprised to find some craterless regions on the surfaces of Pluto and Charon, suggesting very recent geologic change).

The more likely culprit, according to Marchi, is ice. When ice is slightly warm, but not cold enough to melt, it can be a somewhat flexible material that can move and shift over time. The measured density of Ceres suggests that up to 30 percent of the dwarf planet could be made up of ice, Marchi said. The movement of that ice over time might be enough to erase evidence of meteorite impacts.

"Eventually, the [crater count] may not be so striking once we take into account all those processes," he said.

Scientists are interested in the life story of Ceres because it's a relic of the early solar system — it hasn't changed much over the last four billion years, and therefore it may reveal information about what happened during the solar system's adolescent stage, including how the planets formed and evolved.

"It's a complicated story, but by putting all these things together I'm confident we can uncover the evolution of some of these [asteroid belt] objects," Marchi said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter