What's Inside Saturn Moon Enceladus? Geyser Timing Gives Hints

Eruptions of vapor and ice that stretch for miles above the surface of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus experience a mysterious delay that could be due to a weak interior, new research suggests.

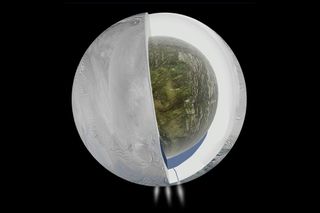

The geysers that burst from the surface of Enceladus indicate that this Saturnian satellite is more than just a ball of ice. Scientists believe a liquid-water ocean exists beneath the solid surface, and that life could potentially survive there. A better understanding of the geysers could provide clues as to what is going on in that subterranean environment, the study scientists said.

Previous work has suggested that the geysers are caused by the tidal pull of Saturn on Enceladus, but the timing of those explosions with the motions of the two bodies doesn't quite line up based on models. The new research provides insight into what kind of internal arrangement might be responsible for the timing of the geysers. [Inside Enceladus, Icy Moon of Saturn (Infographic)]

Enceladus is Saturn's sixth-largest moon, a 310-mile-wide (500 kilometers) satellite covered in an icy shell. In 2005, NASA's Cassini spacecraft spotted water vapor and icy particles erupting from its south pole — explosions that may have their origin in water from a giant, hidden ocean.

The geysers on Enceladus vary in how active they are, depending on where the alien moon is on its slightly "eccentric," or oval-shaped, orbit, which takes about 1.37 Earth days to complete. This led scientists to suspect that tidal forces trigger the eruptions on Enceladus — as the strength of Saturn's gravitational pull on Enceladus varies over time, so too does the amount of stress on giant cracks in the alien moon's icy shell, opening and closing these rifts.

However, the eruptions seen from Enceladus always seemed delayed by several hours with respect to predictions based on simple tidal models. To help solve this mystery, scientists developed more complex 3D models that varied the viscosity of the alien moon's interior to see how that might influence how Enceladus behaved.

"Previous predictions were too simple, in that they ignored important details of the structure of Enceladus," study co-author Francis Nimmo, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of how thick it is — how much it resists flow. For example, water is a relatively low-viscosity fluid, while honey is a relatively high-viscosity one.

The scientists found that although a strong, high-viscosity ice shell would react instantly to tidal forces, a weaker, low-viscosity ice shell would react more gradually.

"Enceladus experiences tides from Saturn, which provide a force on the ice shell," Nimmo said. "The ice shell flows in response to these forces, and because the flow is quite slow, the response is delayed by several hours."

The researchers propose two potential models that could explain the delay seen in Enceladus' geysers. One involves a global subsurface ocean, with an ice shell more than 30 miles (50 km) thick that churns throughout the entire ocean. The other involves a subsurface sea limited to the south polar region. In this model, the churning of the ice shell is limited to an area right above this sea in a layer that is only about 18 miles (30 km) thick.

"The timing of geyser activity gives us an insight into the interior of a rather complicated planetary body," study lead author Marie Běhounková, a planetary scientist at Charles University in Prague, told Space.com.

More data from the Cassini spacecraft could help determine which of these models is more likely, the researchers said. They detailed their findings online in the July 6 edition of the journal Nature Geoscience.

Understanding more about the geysers of Enceladus would shed light on the alien moon's interior and on whether or not life dwells there, said Cassini imaging team leader Carolyn Porco.

"All we have to do is fly through the plume with the proper instrumentation and we could make great progress towards answering the question, 'Is there biological activity?'" Porco told Space.com. "A group of us are in the throes of designing a mission to do just that. Anything that assists us in knowing how to plan such a mission is of vital importance to our next exploratory steps at Enceladus.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us