Supermassive Black Holes Are Not Doughnuts

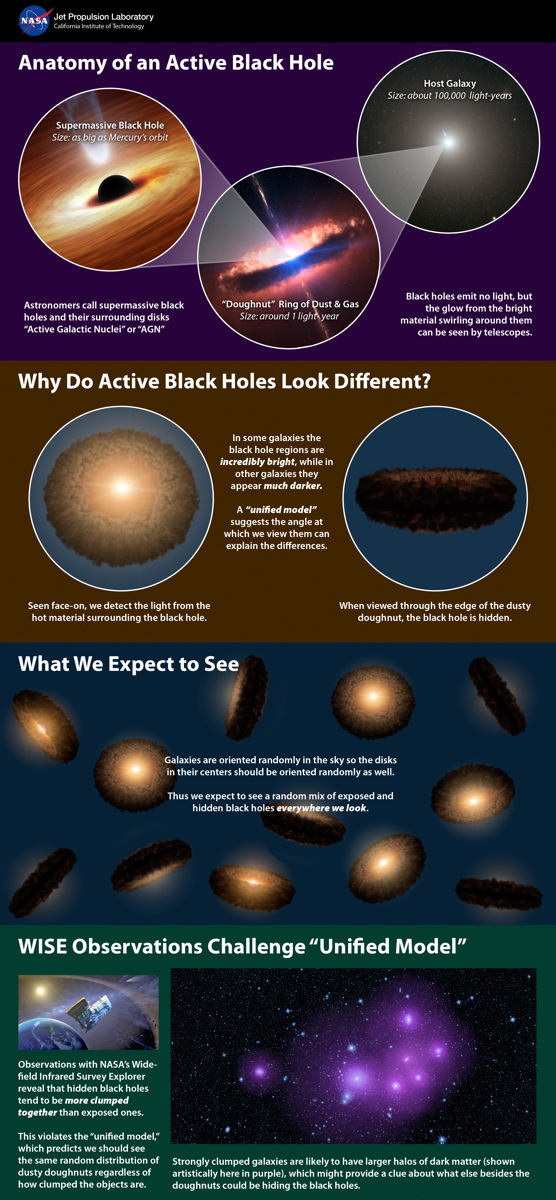

Conventional thinking suggests that the most massive black holes possess a ringed doughnut-shaped torus of gas and dust trapped in orbit around them. But if we know one thing about black holes, they're anything but conventional.

Now, astronomers have analyzed data from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) of thousands of supermassive black holes to find that the "torus model" may be woefully inadequate when explaining what is actually going on.

ANALYSIS: Lasers to Solve the Black Hole Information Paradox?

Most galaxies appear to contain a supermassiveblack hole in their cores. With masses in the realms of millions to billions of solar masses, these objects truly are the heavyweights of our Universe. With all this mass comes a powerful gravitational field that dominates galactic cores, pulling in any matter — stars, planets, dust, gas, possibly unlucky extraterrestrials — to the black hole's event horizon. [10 Strangest Black Hole Discoveries]

Interactions between infalling matter and the supermassive black holes can generate huge quantities of energy, creating what are known as active galactic nuclei, making the effects of the black hole easy to observe.

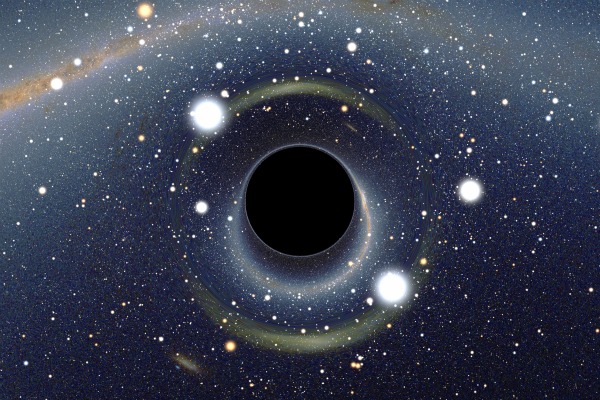

In the 1970s, astronomers developed a unified theory that could explain active supermassive black hole observations. The theory arose from the fact that some active black hole emissions could be easily seen by observatories while others seemed obscured by dust. To explain this, astronomers came up with the idea that supermassive black holes must be surrounded by a torus, or ring, of dusty material (as shown in the artistic rendering above).

ANALYSIS: Monster Telescope Combo Spies Feeding Black Hole

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Therefore, given their random orientation as observed from Earth, some rings may appear "edge on" (thereby blocking our view of the black hole) or we may be observing the ring from above (revealing the black hole).

Since this unified theory was suggested, it has generally matched observations of black holes and helped us understand how they influence the evolution of their host galaxies.

ANALYSIS: How to Make a Bigger Black Hole Jet

As expected, after surveying 170,000 galaxies containing supermassive black holes at their cores, the WISE observations showed some black holes that could be seen, whereas others appeared obscured (in line with the torus model), but it also revealed a peculiar pattern. When looking at black holes inside massive galaxies that are clumped together as a part of galactic clusters, more supermassive black holes seemed to be obscured.

This bias toward obscured black holes in large clusters cannot be accounted for if we just consider the unified theory. Why would supermassive black holes inside galaxies that are clumped in clusters be preferentially obscured by their dusty doughnut-shaped rings?

"The main purpose of unification was to put a zoo of different kinds of active nuclei under a single umbrella," said post-doctorate astronomer and lead researcher Emilio Donoso, of the Instituto de Ciencias Astronómicas, de la Tierra y del Espacio in Argentina. "Now, that has become increasingly complex to do as we dig deeper into the WISE data."

ANALYSIS: How Do Supermassive Black Holes Get So Fat?

Donoso and his team's work indicates that some mechanism beyond the unified model is at work and they suggest dark matter may have a part to play.

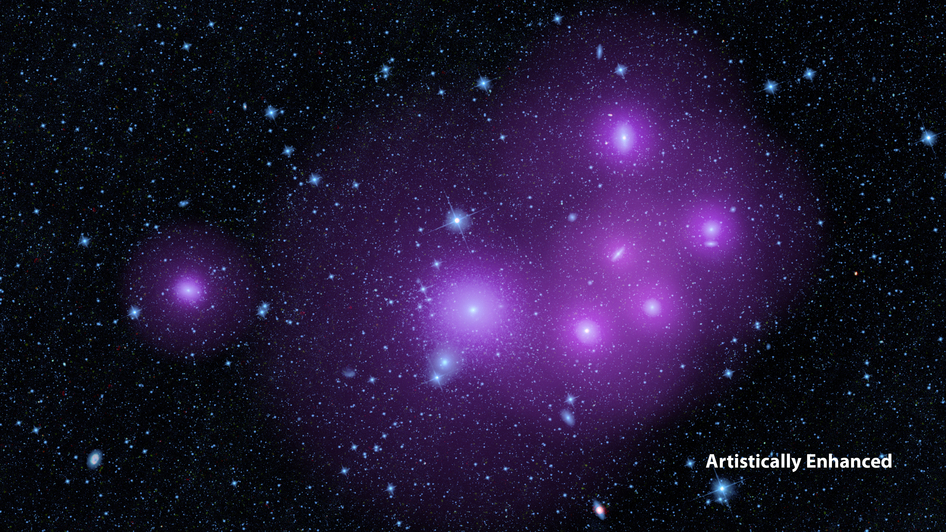

It is well known that "invisible" dark matter — a type of non-baryonic matter that pervades the entire universe — exerts a strong gravitational influence on galaxies and clusters of galaxies. It is also known that there is a vast, large-scale dark matter structure that forms a huge cosmic "web." At nodes in this dark matter web — known as halos — galaxies form and collect as clusters, apparently anchored in place by the gravitational oomph of dark matter halos. It is also known that some of the most massive supermassive black holes reside in the biggest, most massive clusters that, in turn, is the location of the biggest halos of dense dark matter.

Could dark matter halos have a role in obscuring the clustered supermassive black holes from view? Is dark matter somehow adding more complexity to black hole torus?

For now, we just don't know and further work is needed to understand this bias. But it is fascinating to think that the 'textbook' idea of an active black hole sporting a doughnut-shaped torus may need some reworking.

For more on this fascinating WISE discovery, browse the NASA news release.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.

![Black holes are strange regions where gravity is strong enough to bend light, warp space and distort time. [See how black holes work in this SPACE.com infographic.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/8GbuLi8DVtx8HoZeSyndT7.jpg)