Clouds On Alien Planet Mapped for 1st Time (Image)

Scientists have created the first-ever cloud map of a planet beyond our solar system.

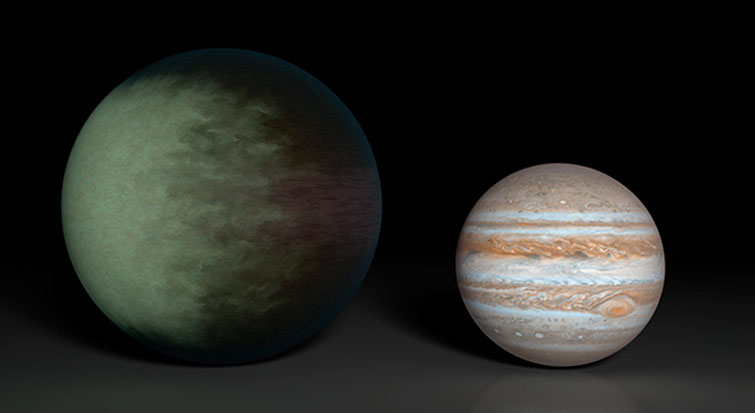

Although the roughly Jupiter-size Kepler-7b lies far closer to its star than scorching-hot Mercury does to the sun, astronomers using NASA's Kepler and Spitzer space telescopes have determined that clouds exist high up in the western portion of the exoplanet's atmosphere.

"By observing this planet with Spitzer and Kepler for more than three years, we were able to produce a very low-resolution 'map' of this giant, gaseous planet," study lead author Brice-Olivier Demory, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said in a statement. "We wouldn't expect to see oceans or continents on this type of world, but we detected a clear, reflective signature that we interpreted as clouds." [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

One of the first five exoplanets confirmed by the Kepler spacecraft, Kepler-7b orbits only about 5 percent as far from its star as Earth does from the sun.

Kepler's visible-light observations revealed a bright spot in the western hemisphere of the planet. Researchers orginally thought this patch may have been heat, but observations by Spitzer changed their minds.

Spitzer's infrared eyes revealed that Kepler-7b's temperature was between 1,500 and 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (820 and 980 degrees Celsius) — surprisingly cool for such a close-orbiting planet, and too cool for heat to be the source of the mysterious brightness.

So researchers concluded that what Kepler actually observed was stellar light bouncing off upper-atmosphere clouds.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Kepler-7b reflects much more light than most giant planets we've found, which we attribute to clouds in the upper atmosphere," co-author Thomas Barclay, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., said in a statement. "Unlike those on Earth, the cloud patterns on this planet do not seem to change much over time — it has a remarkably stable climate."

According to the study, which will be published in an upcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters, the west side of the planet is dominated by high clouds, while the east side boasts clear skies.

"With Spitzer and Kepler together, we have a multi-wavelength tool for getting a good look at planets that are trillions of miles away," said Paul Hertz, director of NASA's astrophysics division. Hertz was not involved in the study. "We're at a point now in exoplanet science where we are moving beyond just detecting exoplanets, and into the exciting science of understanding them."

Kepler-7b was discovered in 2010. Although it is 1.5 times larger than Jupiter, it less than half as massive. Its Styrofoam-like density is less than that of water, making it one of the least-dense planets ever discovered.

Along with four other known planets, Kepler-7b orbits a star more massive than the sun. The cloudy planet orbits the star, Kepler-7, once every five days; its siblings have similarly short periods. The system lies in the Lyra constellation.

Kepler has identified more than 3,500 planetary candidates since its March 2009 launch; more than 150 of these have been confirmed so far by follow-up observations.

The spacecraft identified potential exoplanets by watching for the brightness dip they caused when crossing in front of their parent stars from Kepler's perspective.

In May of this year, the second of Kepler's four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed, keeping the telescope from aiming precisely and halting its exoplanet hunt. However, scientists are still poring over four years' worth of data, identifying potential candidates.

NASA is currently trying to figure out a new mission for Kepler, whose other systems remain in good working order.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky