Pluto Colder Than Expected

Earth-bound astronomers taking Pluto's temperature have confirmed suspicions that the planet is colder than it should be. It's thought that the planet's lower temperature is the result of interactions between its icy surface and thin nitrogen atmosphere.

Using the Submillimeter Array, or SMA, a network of radio telescopes located in Hawaii, astronomers found that Pluto's average surface temperature was about 43 K (-382 degrees F) instead of the expected 53 K (-364 degrees F), which is what the temperature of Pluto's largest moon, Charon, is.

Unlike Pluto, Charon has no atmosphere, so its surface temperature was what astronomers predicted based on its geological makeup and reflectivity.

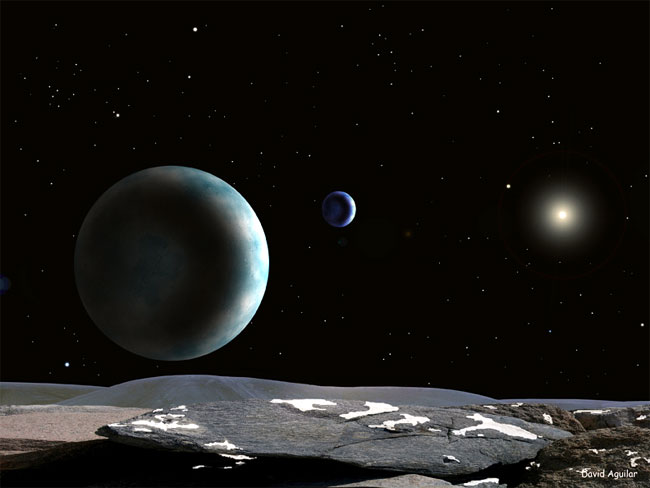

Pluto is located thirty times farther away from the Sun than Earth, about three billion miles, and receives only about 1/1000th of the light that our planet receives. Pluto's surface temperature varies widely because of its erratic orbit, which can send it as close as 30 astronomical units (AU), or as far away as 50 AU.

An AU is the average distance from the Earth to the Sun, about 93 million miles.

A popular planet

Pluto has been the focus of a lot of scientific attention lately. Its status as a planet is currently being debated since the discovery in July of an even larger object located even farther out in the solar system, in a region of space known as the Kuiper Belt. In October, astronomers announced the discovery of two tiny, new moons orbiting the planet, each one only 30 to 100 miles (45 to 160 kilometers) in diameter.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers have suspected since the early 1990's that Pluto is colder than it should be, but they were unable to confirm their suspicions until recently because it was difficult to tease apart the heat emissions of Pluto from nearby Charon.

Charon is unusually large for a moon and scientists are still not sure how it and Pluto became paired. According to one hypothesis, Pluto was struck long ago by another body that was nearly identical in size, spinning off Charon as a result.

From Earth, Pluto and Charon appear about 0.9 arcseconds apart, and trying to tell them apart is like trying to make out the length of a pencil from 30 miles away.

The SMA is the first telescope able to make the required measurement. Other telescopes like the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico have higher resolution than the SMA, but are less sensitive to colder objects.

"We're the first to have the combination of resolution and sensitivity to be able to do this experiment," said Mark Gurwell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a co-author on the study.

Anti-greenhouse effect

Astronomers think Pluto's colder than expected temperature reading involves interactions between nitrogen ice on the planet's surface and the nitrogen gas that makes up its atmosphere.

The two forms of nitrogen are in a constant state of careful flux: as Pluto moves away from the Sun, the nitrogen gas "condenses," freezing and falling back to the surface as ice. The opposite happens when Pluto is closer to the Sun.

Planets like Venus and Earth experience a natural greenhouse effect, where sunlight energy striking the surface is absorbed and used to heat the surface. On Pluto, the opposite happens.

"Pluto is a dynamic example of what we might call an anti-greenhouse effect," Gurwell said.

Instead of being absorbed and warming the surface, sunlight striking Pluto is used to convert nitrogen ice on its surface into gas. A similar process happens when humans sweat: the evaporation of sweat from the skin has a cooling effect because the evaporated water carries away the body's excess heat.

The finding could apply to other planets in the solar system which have condensable atmospheres like Mars, or even to extra sola- planets, Gurwell told SPACE.com.

In the future, Gurwell hopes that astronomers will be able to make even more precise measurements of Pluto using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) currently being built in Chile. The ALMA is scheduled for completion in 2012 but early scientific experiments could begin as soon as 2008.

Gurwell expects that the ALMA will allow astronomers to see where on Pluto's surface nitrogen gas is being generated and whether the atmosphere is spread out evenly across the entire planet or concentrated in hot spot like on Saturn's moon, Enceladus.

"We're breaking new ground, laying the foundation for work that will happen in the future," Gurwell said.

The finding will be presented at the 2005 meeting of the American Astronomical Society that begins on Jan. 8 in Washington, D.C.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.