Space Tourism Is About to Push Civilian Astronaut Medicine Into the Final Frontier

Are you healthy enough for spaceflight, or just wealthy enough?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

For decades, access to space has been limited based on a set of preconceived beliefs about human bodies — but capitalism is chipping away at those restrictions.

Soon, people with enough money will be able to buy trips into space. And as wealth redefines the traditional "right stuff," the field of space medicine will need to rethink its approach. The discipline will still need to evaluate and support human health within the context of spaceflight, but specialized space medicine professionals will exert much less control over who flies and who doesn't. In a new paper, a trio of space medicine experts kickstart that process by reviewing some critical aspects of the field for general practitioners who may find themselves caring for patients planning flights.

"Historically, space medicine was the purview of doctors that took care of highly selected populations of astronauts — individuals that are exceptionally healthy, exceptionally fit, exceptionally stress-tolerant, have no medical conditions of any sort," lead author Jan Stepanek, a physician specializing in space medicine at the Mayo Clinic, told Space.com.

Related: Second NASA Astronaut to Spend Nearly a Year in Space — For Science

But when it comes to space tourism, none of those superlatives is guaranteed.

That's the entire point of space tourism, after all: Simple wealth will allow someone to become an astronaut without needing to deal with all the pesky screening and training and limited seating built into governmental spaceflight programs.

NASA's approach to spaceflight has always been to ground anyone the agency's experts believe may not be able to physically or psychologically handle spaceflight. "The trouble that [Stepanek and his co-authors] identify, and I think they're absolutely right, is at NASA we can screen out pathology," Richard Scheuring, a flight surgeon at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Texas, told Space.com. "That makes the practice of space medicine an order of magnitude more straightforward and less complicated."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Not so for space tourists. That isn't necessarily a bad thing; space medicine could use a perspective change and papers like this one may push the field that direction, Ashley Shew, an expert in disability studies and the intersection of science, technology and society at Virginia Tech, told Space.com. She noted that the new paper, like most research in medicine and particularly space medicine, starts from the premise that bodies that don't conform to certain ideals are problematic, rather than different.

Space medicine has never confronted the possibility that different could be beneficial, she said, despite occasional glimmers that suggest just that. "The bodies that we've always chosen have been what we consider the best bodies, but those aren't the best bodies for space usually," Shew said. "We have these ideas of what a perfect specimen is supposed to be, we recruit on these categories that you have to satisfy in a certain way."

Who has gone to space

Nearly 600 people have flown in space, but just seven of those have been paying customers, Stepanek and his co-authors wrote. Thousands more have briefly experienced zero-gravity conditions during parabolic flights. And plenty of companies — SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin among them — have set their sights on making space the next hot tourist destination.

So Stepanek and his co-authors wanted to write a paper for general physicians, serving as a summary of existing scientific literature and alerting these doctors to issues they need to consider if a patient is planning to buy a spaceflight. To that end, they sketched out the different levels of expected risk for different types of flight, from very brief suborbital flights all the way up to long-duration planetary missions.

Scientists and doctors still have plenty of questions about how long-term spaceflight in microgravity and beyond affects even the most traditionally "ideal" of astronaut bodies. No NASA astronaut has ever spent a full year in space, and just three have exceeded 200 straight days in orbit, although the would-be fourth, Christina Koch, is living on the space station now.

But the typical space tourism flight, at least in the near future, will be a suborbital journey that lasts just minutes, which poses a much narrower suite of risks to the human body. That's the theory, anyway. Right now, Stepanek and his colleagues don't have nearly the amount of data they need to be confident in their findings. (Their review was published March 14 in the New England Journal of Medicine.)

"What I'm sharing with you is merely extrapolation. The real data will come in when individuals are actually flown," Stepanek said. "I think the only honest answer is that this is going to be and is expected to be a very safe endeavor for the majority of individuals."

Stepanek and his co-authors looked at the challenges that different types of flight may involve. For suborbital flights, those challenges include anxiety, space motion sickness, loud noises, small spaces and g-forces. The authors also cite the results of three ground-based studies conducted by the Federal Aviation Administration using centrifuges that suggest 4 of 5 people drawn from the general population between ages 19 and 89 could tolerate the g-forces associated with a suborbital flight.

Those guinea pigs didn't leave the ground, but other people without the "perfect" bodies of traditional astronauts have already flown. The handful of space tourists who have already flown are the rare example here, and they have brought with them issues like poor vision and lung trouble.

Many more tourists have already experienced zero-gravity conditions for brief snippets of time during parabolic flights. ZERO-G has flown more than 15,000 passengers — including Stephen Hawking before his death last year of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Michelle Peters, director of research and education at ZERO-G, said her company is mimicking the approach of commercial airliners: Passengers need their own physician's approval to fly and each ZERO-G flight is staffed by flight attendants with basic first-responder skills. (When Hawking, who used a wheelchair, flew, he was accompanied by physicians, but that was arranged independently, not by the company.)

What space tourism may look like

That matches an assumption built into the paper, in which Stepanek and his co-authors posit that space tourism companies aren't likely to staff flights with doctors given that they will last just minutes — too short to allow for much medical intervention, even if in the unexpected case that it's necessary.

That isn't to say it would be wise to simply hop on a flight on a whim: Passengers would need to prepare for the experience. Eric Stallmer, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, a group of more than 80 organizations focused on commercial spaceflight, compares the prospect to the checks and preparation people conduct on their own initiative before setting out to climb Mount Everest or run a marathon. "I would look at it from that perspective," he said. "I would want to be in the best physical shape that I can be in."

Right now, there aren't any rules requiring space tourism companies to set or meet any health criteria for accepting passengers — they just need to have each customer sign a statement saying they understand the risks of such a flight. (Although Scheuring notes that there's no guarantee scientists have identified all of those risks to date, especially for passengers without NASA's prerequisite "perfect" body.)

Stallmer believes there's a role for glamorizing the training that can help commercial space flyers get a taste for what their body will experience and how they will handle it, as well as emergency procedures.

Stallmer pointed to Virgin Galactic's plan for customer flight preparations as an example of how companies should look to teach passengers what they need to know to stay safe in flight. "It's this total astronaut experience ... that's what brings the allure," he said. "It's like trying to make reading a book fun for a teenager." (Virgin Galactic, which is preparing to fly commercial passengers — at $250,000 a seat — with launches expected to begin later this year, did not respond to requests for comment.)

But chances are that by getting a few key organ systems checked, sampling different gravity conditions and understanding what to do in an emergency, a space tourist brushing the boundary of space should face smooth sailing. Scheuring agreed that during suborbital tourism flights, there likely isn't much that can go wrong. "It's not a big deal," he said.

And the more people fly, the more confident doctors can be in their risk assessments about tourist flights. "The more data we have, the stronger the database and the evidence for decisionmaking becomes," Stepanek said. "Right now, it's zero, it's based on orbital spaceflights and the limited exposure we've had to professional test pilots."

As more people with more varied health backgrounds pass beyond the bounds of gravity, that will change, and doctors could learn a lot about how human bodies respond to spaceflight in the process.

"One of the fascinating things about medical discoveries is we find about a lot of things by people with disease states being exposed to novel environments," Marsh Cuttino, a former physician consultant to NASA who has flown on parabolic flights with ZERO-G, told Space.com. "I think we are going to learn a lot because these are not the average astronauts of years past."

Who may never go to space

Chances are, some barriers to spaceflight will never disappear, and not necessarily ones that are particularly fair, even beyond the massive price tag.

When it comes to short, suborbital flights — the sort of flights space tourism companies are currently targeting — space medicine experts have narrowed their worries to a few key red flags. Those areas of concern include the heart, lungs and spine, doctors who spoke with Space.com said. Those health issues don't necessarily line up with some of the conditions doctors are most concerned about on Earth, like diabetes or high cholesterol, Stepanek noted, which would likely not be problematic for suborbital flights.

But still, and particularly so for longer flights, sheer money may not be a clean pass into space. "It's not for everybody," Scheuring said. "I think that's something that folks are going to have to get out in the community, is that just because you've got a lot of money doesn't mean you're necessarily going to be able to handle the factors and environments of spaceflight."

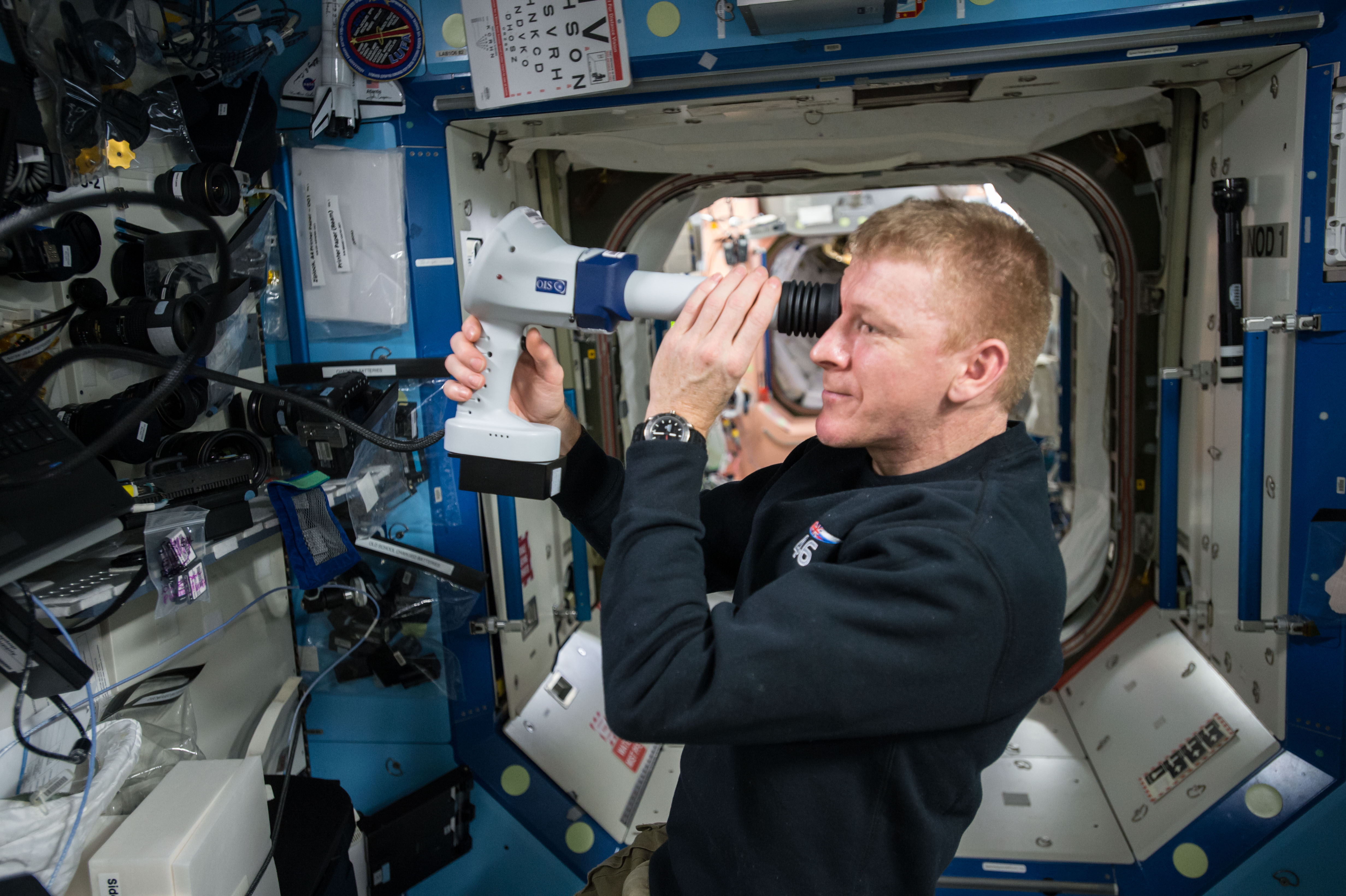

That's particularly true for longer flights with conditions that would make having specialized equipment available wise. There are plenty of medical devices that can't fly in space — there aren't versions that work in microgravity or they're simply too large to make launch feasible. Take, for example, ventilators, bulky machines that keep people breathing when something goes wrong. Understandably, NASA has never bothered to develop this sort of medical technology. "We don't send that kind of pathology in space, so why would we need that," Scheuring said.

But pragmatism aside, preconceptions about who will be flying may also block would-be space tourists, Shew said — just as they have for decades.

Thinking ahead

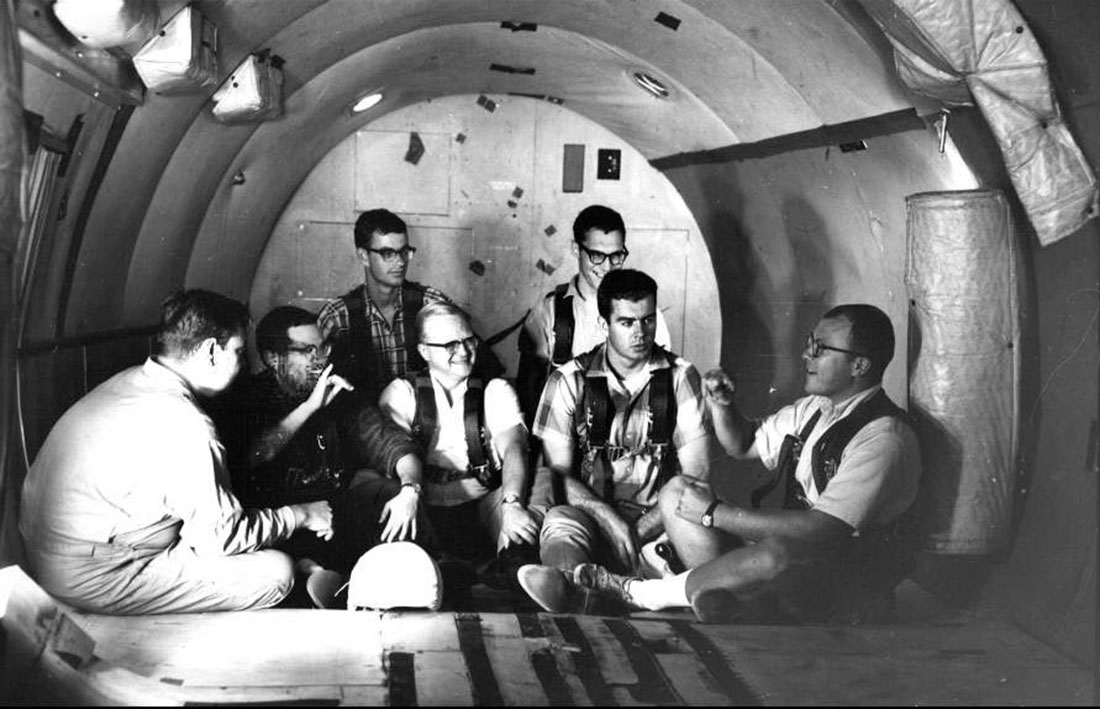

In the late 1950s, the agency recruited 11 men born deaf for a series of experiments designed to probe their lack of motion sickness, a side effect of their lack of hearing. NASA never intended to make these men astronauts, of course: Scientists instead wanted to take the resulting data and apply it to ease the spaceflights of traditional, "perfect"-bodied astronauts.

Space tourism companies may do well to rethink that last bit, Shew said. "Are you going to advertise at Gallaudet [a university for the deaf and hard of hearing]? That would make sense to me, right — you don't have to worry about people puking in your cabin and ruining it on its first flight," she said.

And that makes the broadening of eligibility for spaceflight an opportunity — if it's done right. But there's plenty of potential for it to be done wrong. "I'm afraid that, like other things before it, people will try to sell disabled people spaceflight as a curative measure … maybe it will start to be seen as sort of a quacky medical situation," Shew said — and for an experience with six-digit price tags, that's particularly troubling, as employers can legally pay disabled workers less than the minimum wage.

Or, space tourism companies could take the opposite approach, accepting some preexisting conditions but banning people with other conditions that they feel could make the company vulnerable. "Disabled bodies are often viewed as riskier bodies, not only to have but also to include in things," Shew said.

Space tourism is most frequently compared to commercial airliners — and Shew is concerned that may remain the case. Airports and airplanes assume people can navigate long hallways, boarding stairs, and narrow corridors between built-in seats. "Even casually how you get on a spacecraft will matter," Shew said. "I feel like businesses should be recruiting disabled people to avoid so many of the technological disasters we've seen."

The way space tourism companies choose to balance inclusion and exclusion, safety and risk, will shape how normal people — not just carefully tuned astronauts — leave the bounds of Earth. Where they choose to fall along those spectra will also shape what happens next in the industry itself.

"I don't think any of the commercial space practitioners are going to take any unreasonable risks with people," Scheuring said. "I think they'll find out really quickly, if they try to take shortcuts, they're going to get burned."

And the more that can be sorted out before launch — of individual flights and of whole programs — the better. "Once the rocket fires, there's no such thing as raising your hand and saying, 'I change my mind,'" Stepanek said. "You're going."

Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct the past affiliation of Marsh Cuttino.

- In Photos: Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo Unity Soars to Space in 4th Powered Test

- Photos: The First Space Tourists

- Prepping for Zero Gravity: Anti-Barf Briefings and Last-Minute Practice

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.