March night sky wonders: Strange sights to see every year

March is a month of transition, as we change seasons from winter to spring.

March is a month of transition, as we change seasons from winter to spring. And at this particular time of year, we can look into the night sky for some sky objects with rather unusual aspects.

Here's a tour of some tantalizing targets for skywatchers that are visible each year in March, and the odd stories behind them.

If you need some gear to observe these objects, check out our guides for the best telescopes and best binoculars. If you're looking for a camera, here's our overview on the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

The sky of the grand old man of Victorian poetry

On more than one occasion over the years I have made reference to the poem "Locksley Hall" by the eminent English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892). These two lines are quite familiar to many amateur astronomers, since they are frequently quoted in connection with the Pleiades star cluster:

"Many a night I saw the Pleiads, rising

thro' the mellow shade.

Glitter like a swarm of fire-flies

tangled in a silver braid."

But the Pleiades is not the only celestial reference mentioned by Tennyson in "Locksley Hall." For in the two lines immediately preceding the ones about the Pleiades, he also speaks about Orion:

"Many a night from yonder ivied casement,

ere I went to rest,

Did I look on great Orion sloping slowly

to the West."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It turns out that along with being a poet, Tennyson was also intensely interested in science. According to George Lovi (1939-1993), who was a columnist for many years at Sky & Telescope magazine, Tennyson was a "devoted skywatcher who regularly used a 2-inch refractor." His apparent reference to the Orion constellation "sloping slowly to the West" (probably at bedtime) probably referred to a mid- or- late-evening in March, with the mighty hunter tipped over to the right and heading down toward the west.

In contrast, Tennyson's comment of sighting the Pleiades "rising thro' the mellow shade," could not have come at the same time that Orion was sinking in the west. Note that in both cases, he starts off with the words "Many a night" which likely referred to a certain small portion of the year. In all likelihood, in the case of the Pleiades, Tennyson was probably watching them ascend the eastern sky during a mid or late evening in October. And his "fire-flies tangled in a silver braid" comment certainly sounds like a low-power view through his 2-inch telescope.

In the case of Orion's slanting to the west, this is but one example of the way constellations can change their aspect or presentation in our sky. Factors include the position in the sky, the latitude of the observer, and even their closeness to the horizon. Orion appears tipped over one way or another when it's rising or setting, but that's because it is oriented due north-south when it's highest in the southern sky. But many other constellations are oriented differently.

Gemini constellation: Celestial acrobats

Take, for example, the Gemini constellation, also known as the Twins. Here is a constellation that most astronomy books refer to as a winter star pattern. And yet, as we transition from winter to spring this month when nightfall arrives, we find the twin brothers almost directly above our heads. So maybe we can call them a spring constellation?

Gemini is different from Orion because, at their highest, the twins are decidedly slanted in a northeast-southwest direction. When we first see them at nightfall in mid-December, they are positioned just above the east-northeast horizon; it appears that they are lying down on their side, with the older brother (Pollux) resting on his right shoulder. When they cross the meridian, they do not stand straight up and down like Orion, but somewhat tilted in the same way that other constellations like Boötes the Herdsman and Cygnus the Swan do.

And as the night progresses, the twin brothers — almost like acrobats performing a dismount from the parallel bars — end up landing straight up on their feet. Indeed, that's how we see them, standing on the west-northwest horizon at dusk at the start of June, long after most of their winter companions such as Orion and Taurus have departed the scene.

Canopus: A bright star and celestial weather forecast

Also, during March evenings, the second brightest star in the sky, Canopus, is well placed low in the west-southwest sky for those living far enough south to see it. It's about 310 light-years away and possesses a luminosity over 10,000 times that of our sun, along with being eight times as massive and 71 times larger. In theory, if you live south of latitude +37.3 degrees, you can see Canopus. But that isn't always true. Tokyo, Japan, for example, is located at latitude +35.7 degrees, but thanks to the combination of heavy air and severe light pollution, it's all but impossible to see this dazzling yellow-white star as it skims just above the southern horizon.

I've mentioned here how the Beehive star cluster was used to foretell unsettled weather in ancient times and Canopus too attained a role as a weather predictor in Japan in a most unusual way.

Being surrounded by water, Japan is often affected by coastal fog. Japanese tradition had it that if Canopus was visible near the southern horizon, stormy weather was likely to follow. This was because unsettled weather sometimes came on the heels of brisk winds which would sweep the air clean and made Canopus visible. Fishermen of central Japan called Canopus, 'mera-boshi' because of the relatively short time that it appeared above the horizon at this time of year, which is also the season of tuna fishing. Thus, it was believed that Canopus represented the soul of dead fishermen who came from a fishing village called Mera, and that when it appeared it was a sign of an impending storm.

Pleiades: A cosmic car connection

Lastly, coming back to the "swarm of fire-flies" mentioned by Tennyson, how many of you who are reading this are driving a car called the Pleiades? Believe it or not, Subaru is what the Pleiades are called in Japanese. It is derived from an older word 'Sumaru' which was a hunter's trophy necklace made of teeth of all of the animals he caught.

In today's world, the Subaru logo consists of one large star and five smaller stars. In 1953, five Japanese car companies merged to form Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd (FHI), and adopted a 'Subaru' cluster of stars as its official logo for its cars. Supposedly, Fuji Heavy Industries is the big star, and the five smaller stars as the other five companies (Fuji Kogyo, Fuji Jidosha, Omiya Fuji Kogyo, Utsunomiya Sharyo, and Tokyo Fuji Sangyo).

But why are there only six stars in Subaru's logo if it's named after a star cluster that is popularly known as 'The Seven Sisters'? The reason is that to the unaided eye, this cluster of stars appears to only have six stars — two are so close together, they appear to the eye as one. Thus, the Pleiades are known for being a "unification of the stars."

Sirius: The Dog Star and its 'Pup'

The most brilliant star in the nighttime sky can be found at nightfall during March, shining about one-third of the way up from the southern horizon: Sirius, the ‘Dog Star,’ brightest star in the constellation of Canis Major, the Big Dog.

Sirius also provided the first example of the mathematical prediction of an invisible star. In 1844, only two years before his death, the great German astronomer, mathematician, physicist and geodesist, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel announced his conviction that the Dog Star's undulating path through space indicated an unseen companion; what seemingly amounted to a "dark" star.

Several other astronomers verified Bessel's calculations and the American calculating prodigy, Truman Henry Safford (1836-1901) even predicted the location of the unseen star. On Jan. 31, 1862, it was finally seen by young Alvan G. Clark while testing a new 18.5-inch objective lens — then the largest refractor in the world — at Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. This was the same telescope that came into the possession of the original Chicago University and which, in 1887, was transferred to the then-new Dearborn Observatory of Northwestern University; it continues to do good work at Northwestern to this very day.

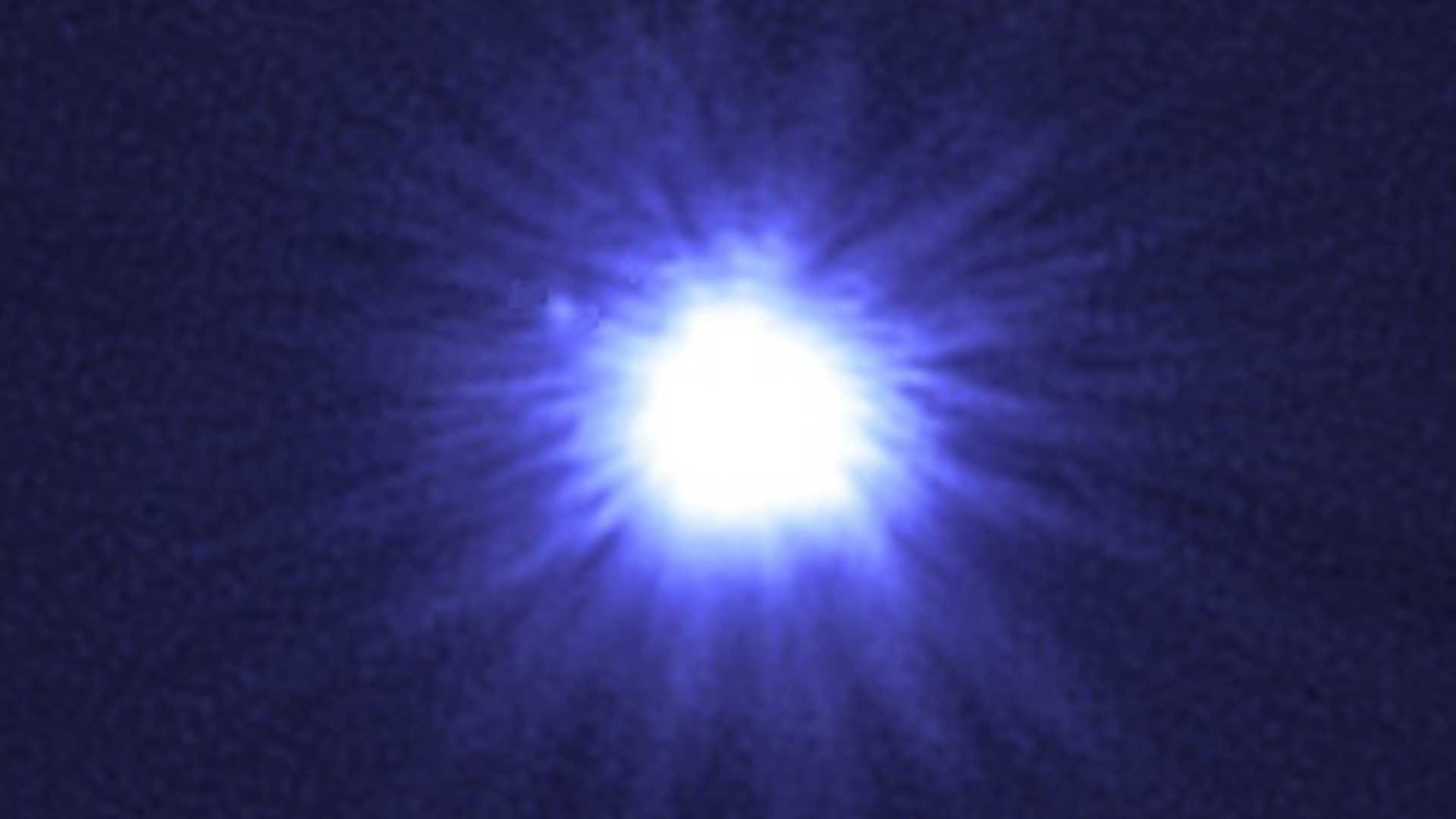

Because Sirius is known as the Dog Star, its companion has been affectionately called the ‘Pup’. Sirius is also known as ‘Sirius A’ while the Pup is ‘Sirius B’. Amateurs with fair-sized telescopes who wish to observe this first-known white dwarf should look for it now because it is just about as far away from its dazzling bright primary as it can be. It is no mean feat to see an 8.4-magnitude star only about 10 seconds of arc distance (equal to 0.0027-degrees) from one that is 10,000 times as bright.

Sirius B revolves around the bright star in a period of 50 years, following an eccentric orbit half again as large as Jupiter's. So, its widest separation from Sirius occurs in 2025, 2075, etc.

Last February, Frank Melillo, an assiduous amateur astronomer based in Holtsville (Long Island), New York, was able to secure a photograph of the Pup adjacent to Sirius. He writes to Space.com:

"I reprocessed this image of Sirius' white dwarf 'Pup.' It seems better with brighter image and I colorized it. Note how bright Sirius is with its rays when comparing it with the white dwarf (the Pup is located on the NE side of Sirius, upper left). I don't think I can get any better than this. Still, it is difficult to see the white dwarf visually through the eyepiece unless you have something like an occulting bar or a disk to block off Sirius' brightness."

In 2005, using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers determined that Sirius B has nearly the same diameter as Earth at 7,500 miles (12,000 km), yet possesses a mass 98% that of our sun. According to the most recently determined values, Sirius B has a density of about 92,000 times that of the sun, or 125,000 times the density of water. If we could somehow transport a teaspoon of this star's material to Earth it would weigh nearly 3 tons.

The Crab Nebula

Another very unusual object can be found just over 1-degree to the northwest of the star Zeta Tauri, the dimmer and lower of the two stars that mark the horn tips of Taurus the Bull. It is the wisp of nebulosity, familiar to most deep-sky observers as the Crab Nebula, discovered by the English physician and amateur astronomer John Bevis in 1731 and again by Charles Messier in 1758. Thereupon, the latter astronomer resolved to make a catalog of these nebulae and clusters that he was always stumbling over in search of comets. Messier wrote:

"What caused me to undertake the catalog was the nebula I discovered above the southern horn of Taurus on September 12, 1758, while observing the comet of that year… This nebula had such a resemblance to a comet, in its form and brightness, that I endeavored to find others so that astronomers would not confuse these same nebulae with comets just beginning to shine."

The Crab Nebula was the first on Messier's original list of 103 objects and hence became known as Messier 1 (or M1). Other astronomers using side notes in Messier's texts eventually filled out the list up to 110 objects.

Most of the ‘comet masqueraders’ on Messier's list turned out to be galaxies, star clusters, or glowing clouds of gas and dust. But the Crab is unique in that it contains a peculiar faint star near its center, that noted astronomers of the early 20th century such as Edwin Hubble and Jan Oort considered to be the stellar remnant of the famous supernova of 1054 A.D. On the morning of July 4th of that year, a star suddenly appeared in the eastern dawn sky, which, within a matter of days became so bright that it was evident even during the daytime. For two months it shone forth and then began to fade, finally completely disappearing from view on April 6, 1056.

In 1968 it was found to be emitting light flashes in step with the 30-per-second pulsations of a strong radio source: a pulsar, or neutron star, the collapsed core of a massive supergiant star, which at one time contained a total mass somewhere between 10 and 25 times that of our sun. The Crab Pulsar was the very first ever detected (today we know of over 2000).

And if you think white dwarf stars like the Pup are compressed, they cannot even begin to compare with neutron stars. Except for black holes, neutron stars are the smallest and densest currently known class of stellar objects, having a radius on the order of just 6 miles (10km) and yet are nearly one and a half times more massive than our sun. A sugar cube of neutron star matter would weigh about 100 million tons on Earth.

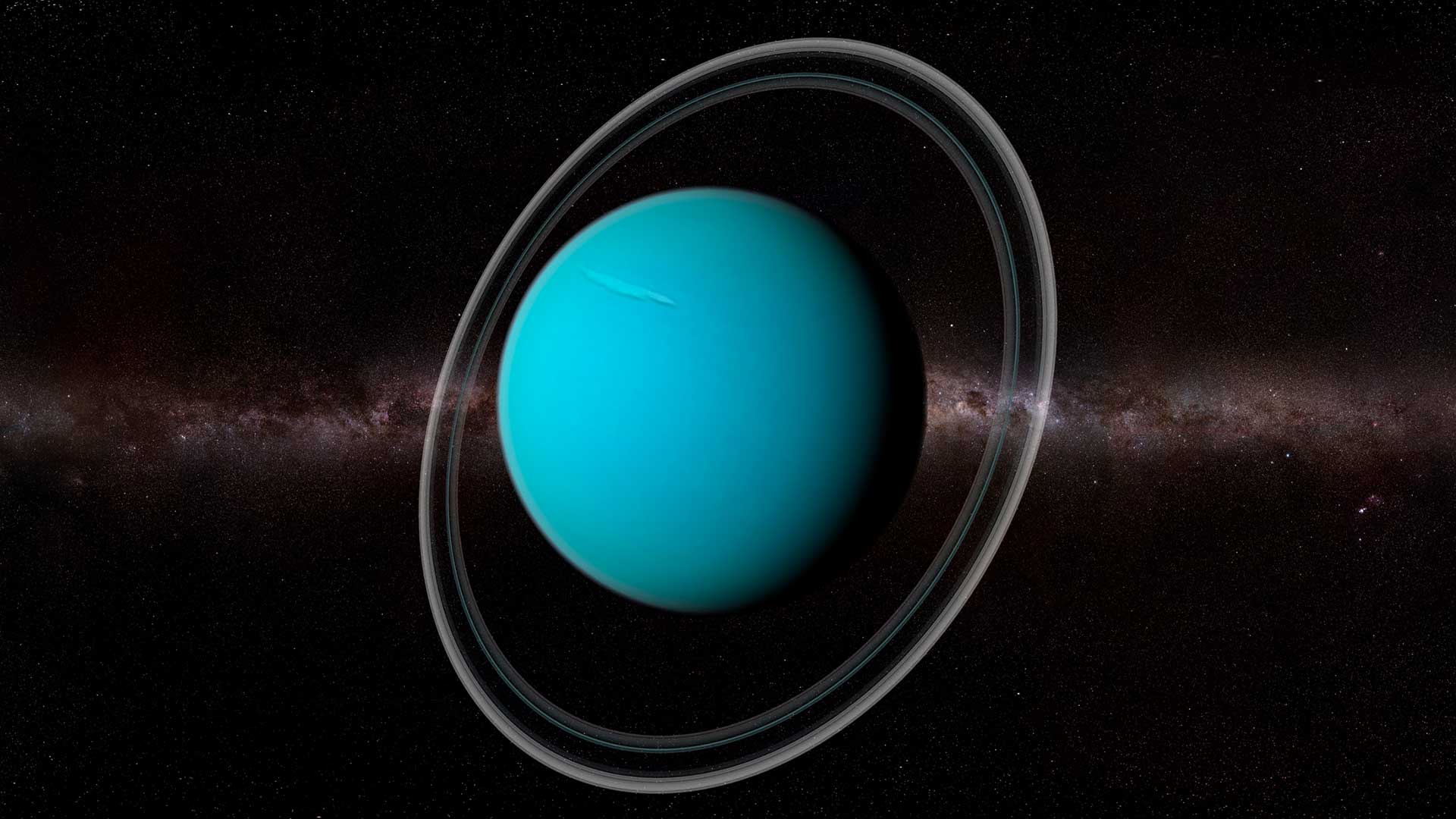

March 13: Discovery of Uranus

March 13 is a rather auspicious date in astronomical history, marking the discovery of two famous heavenly bodies with the aforementioned star Zeta Tauri playing a small role in one of them. On March 13, 1781, William Herschel, an obscure English organist and amateur astronomer in Bath, UK was sweeping the sky with a 6-inch reflector when he noted:

"Near Zeta Tauri the lowest of the two is a curious either nebulous star or perhaps a comet at two-thirds of the field's diameter."

The object was in slow movement from night-to-night. For about a year Herschel thought he had discovered an unusual comet, until Anders Johan Lexell, a Finnish-Swedish astronomer who spent much of his life in St. Petersburg, Russia calculated that its orbit was almost circular and larger than that of Saturn. It was a new major planet.

Herschel soon became famous and in recognition of his achievement, King George III promised him an annual stipend on condition that he move to Windsor so that the Royal Family could look through his telescopes. This is likely the reason that when presented with the opportunity to name the new planet, Herschel proposed Georgium Sidus (George's Star), or the 'Georgian Planet' in honor of his benefactor, the king. But in 1782 German astronomer, Johann Elert Bode, proposed successfully that the new planet should be named Uranus; for just as Saturn was the father of Jupiter, Herschel's new planet, said Bode, should be named after the father of Saturn.

March 13: Discovery of Pluto

March 13 is also important in the history of the discovery of another world besides Uranus. On that date in 1930, it was announced that 'Planet X', which had been hypothesized since 1906 by American astronomer Percival Lowell, had been found. The announced position was very close to the star Delta in the constellation Gemini the Twins. Later details revealed that the photographic plate containing the new discovery had been exposed by Clyde W. Tombaugh at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona on Jan. 23. But why did it take seven weeks to announce the discovery?

Two reasons. The first was to allow for extra time to better scrutinize this very faint object and the second was because March 13, 2022 would be the 75th anniversary of the birth of Percival Lowell who died in 1916 at the age of 61.

An 11-year girl English girl named Venetia Burney suggested that the new planet be named Pluto; Tombaugh liked the name because it started with the initials of Percival Lowell and it was quickly adopted on May 1st, 1930. Pluto was a recognized planet until 2006, when the International Astronomical Union (IAU) demoted it to a dwarf planet, based primarily on its unusual orbital characteristics and very small size.

Many astronomers felt that the discovery of Pluto was the result of devotion and happy accident and not because Lowell had predicted its position. Astronomer William Henry Pickering made an equally imperfect forecast for a trans-Neptunian planet in 1919 which led to photographing Pluto that same year at Mount Wilson Observatory, but the images weren't found until after the Lowell Observatory announcement.

When Pickering heard that the symbol for Pluto was to be an interlocked P and L he said, "That's pretty good; Pickering and Lowell!"

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.