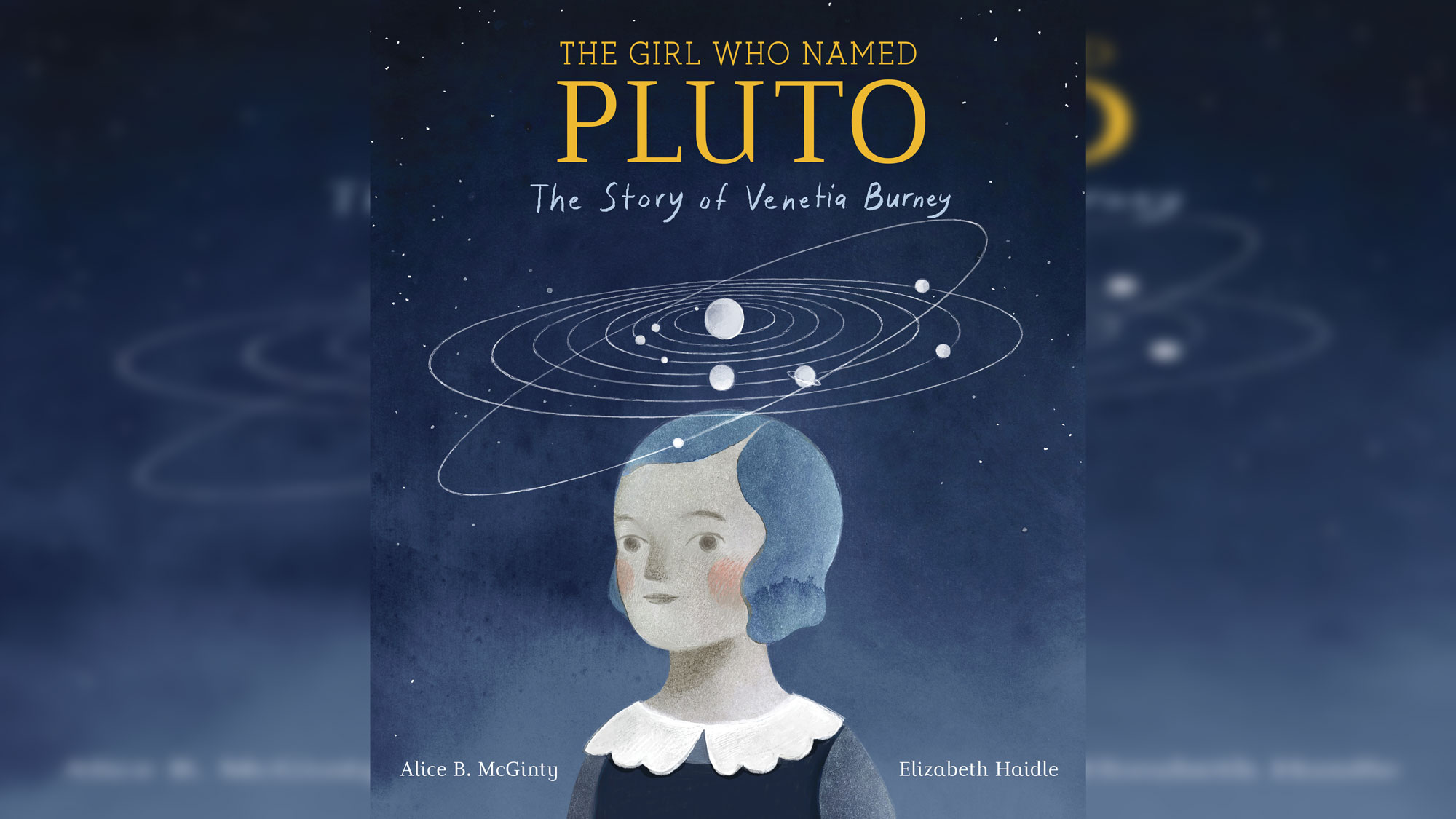

'The Girl Who Named Pluto' Stars in New Picture Book

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Eleven-year-old Venetia Burney was eating breakfast at her home in Oxford, England, on the morning of March 14, 1930, when her grandfather delivered some exciting news. Clyde Tombaugh, an eagle-eyed assistant at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, had discovered visual proof of a long-theorized "trans-Neptunian object" on the edge of the solar system. The scientists gave their discovery the placeholder name of Planet X, but Venetia had a better idea.

"Why not call it Pluto?" she asked. In Roman mythology, Pluto wasn't just Neptune's brother. He was also the ruler of the underworld. And it stood to reason, Venetia said, that because Planet X orbited so far away from the sun, it would be as lifeless, cold and overcast as the shadowlands themselves.

Venetia's grandfather, Falconer Madan, a retired librarian of Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, seized upon the idea. He immediately routed her suggestion to Oxford astronomer Herbert Hall Turner, who in turn dashed off a telegraph to Lowell Observatory. It read: "Naming new planet, please consider PLUTO, suggested by small girl Venetia Burney for dark and gloomy planet."

Related: New Book Shows Children How New Horizons Got to Pluto

Tombaugh and his colleagues voted unanimously for the name, and on May 24, Planet X was officially christened Pluto.

But you'd be forgiven if you haven't heard of Venetia. Alice B. McGinty, an award-winning author of more than 40 books for children, hadn't — at least not until she happened upon a mention of the schoolgirl while researching something unrelated. More than 80 years had passed, but McGinty was hooked.

"An 11-year-old girl had named Pluto? I'd had no idea, and the thought of it intrigued me so much that I stopped working on the other project and dove into Venetia's story, finding out everything I could," McGinty told Space.com. "I had the book outlined in my head within the first few hours, as her story took shape."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And take shape it did. On May 14, Schwartz & Wade will publish "The Girl Who Named Pluto: The Story of Venetia Burney," a picture book that recounts Venetia's history-making turn for kids ages 4 to 8, although "there's plenty" for older children to connect with as well, the author said. And the vintage-flavored illustrations by Elizabeth Haidle make the experience a visual delight.

McGinty said she felt "like a detective" as she plundered libraries, dove through archives and interrogated journalists to unearth telling glimpses of Venetia's budding interest in astronomy, such as a field trip where her classmates modeled the distances between planets using seeds, fruit and golf balls as props.

Though she never met the subject of the book — Venetia Burney, later Venetia Phair, died at age 90 in 2009 — McGinty managed to track down and write to her son, Patrick, who was living in England. "By gosh, it took some time, but he wrote me back and answered my questions," she said.

But even Patrick wasn't able to fill in all of the blanks. McGinty recalled wrestling with the gaps in the historic record. How did Venetia and her grandfather occupy themselves while they were waiting to hear from the Lowell Observatory scientists, for instance? And how did Venetia respond when she was finally told Planet X would henceforth be known as Pluto?

"Oh, how I wish I could have been a fly on the wall, watching as this all unfolded. I would have loved to have seen Venetia's face when she found out she'd named a planet," McGinty said. "I did the best I could, piecing together the information I had and asking myself questions such as, 'What would Venetia have felt? What would she have most likely done?'"

McGinty says she hopes Venetia's tale inspires her readers — girls, in particular.

"I hope girls read it and feel empowered to be part of the scientific process," she said. "I hope boys read it and feel empowered, too, and understand how important girls are to science."

Certainly, Venetia didn't let her age or gender hold her back. By instinctively connecting her love of mythology with her knowledge of space, she understood the relationship between story and science, McGinty said. She quoted Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, who said, "You need to have art in your science brain."

"Finding the story in science helps science come to life: knowing the story of the person behind the discovery, understanding how an achievement was made after many failed attempts," McGinty said. "As Venetia knew, science is about asking questions and working to find answers. Story is about asking questions, too — what happens? What if? Why? — and writing to find the answers. I hope readers will think about the magical connection between science and story and use it to bring science to life in their own lives."

McGinty never returned to her original project. Like Venetia, she gave herself permission to follow where inspiration led. Perhaps her readers will be moved to do the same.

"I hope Venetia's story helps to empower young people to give themselves permission to jump in and participate in science, as Venetia did," she added.

- Pluto's Identity Crisis Hits Classrooms and Bookstores

- Best Kids' Space Books

- Why Do People Love Pluto?

Follow us @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Jasmin Malik Chua is a fashion journalist whose work has been published in the New York Times, Vox, Nylon, The Daily Beast, The Business of Fashion, Vogue Business and Refinary29, among others. She has a bachelor's degree in animal biology from the National University of Singapore and a master of science in biomedical journalism from New York University.