See the moon and Mars buzz a cosmic Beehive this weekend

It is rare when we highlight a celestial event (or events) that involves the zodiacal constellation of Cancer the Crab. In Greek mythology, Cancer was summoned to distract Hercules when he was battling the multiheaded Hydra the Serpent. The crab was crushed by Hercules' foot, but to reward his effort Hera placed it among the stars.

One of my astronomy mentors, the late Dr. Ken Franklin of New York's Hayden Planetarium, used to refer to Cancer as "the empty space" in the sky. Indeed, it's the least conspicuous and second smallest of the 12 zodiacal constellations and quite frankly, aside from being in the zodiac, it's probably noteworthy only because it contains one of the biggest and brightest open star clusters in the sky. More on that in a moment.

Appearing more than halfway up in the west-southwest sky at nightfall in early May, Cancer occupies the seemingly vacant area between two of the sky's showpieces: the stars marking the heads of Gemini the Twins, Pollux and Castor (to its lower right), and the famous Sickle or backwards question mark pattern of stars marking the head and mane of Leo the Lion (to its upper left).

An M&M night (Moon and Mars)

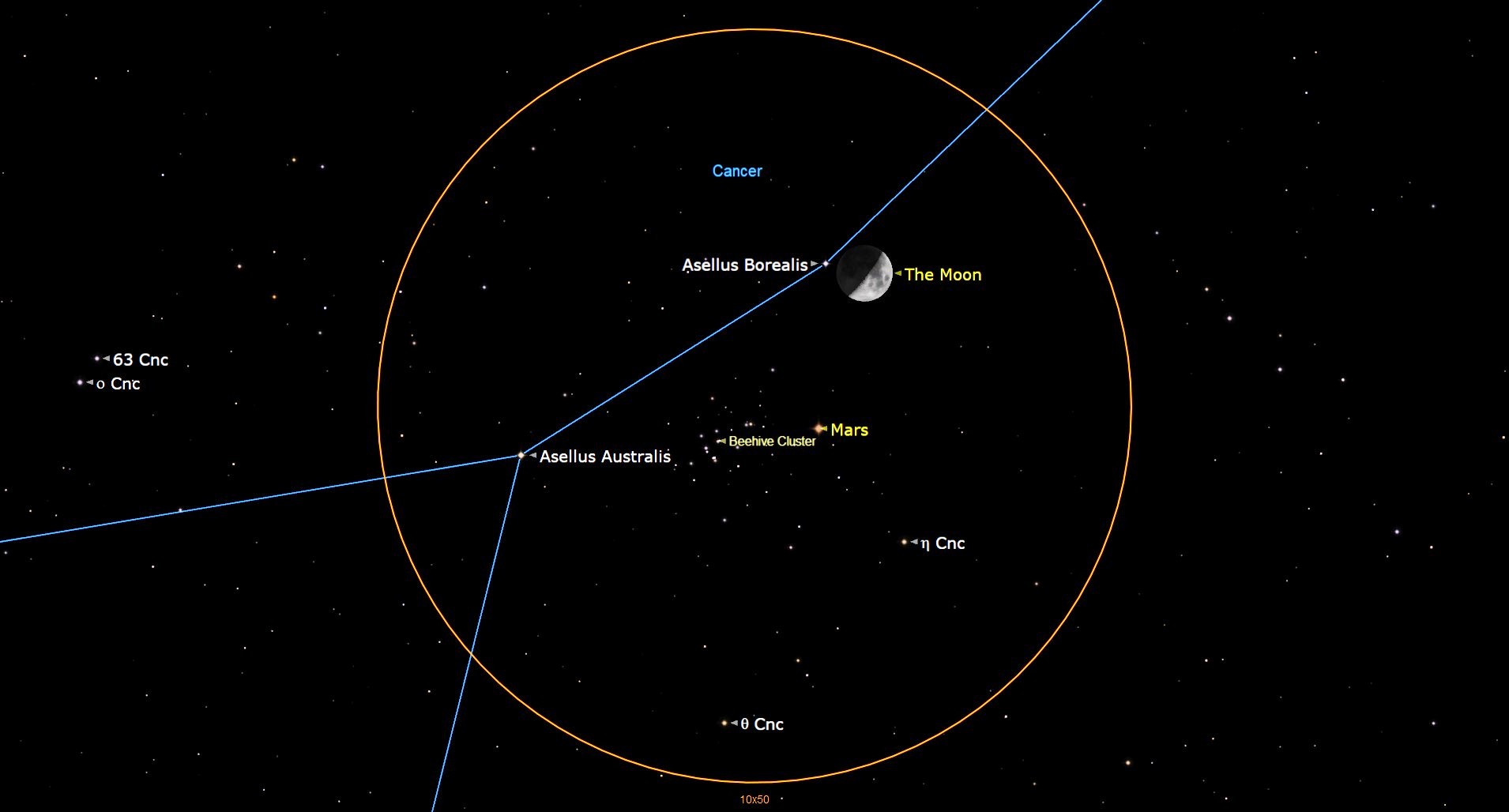

On Saturday evening (May 3), as the sky darkens, check out the rather wide (45-percent illuminated) waxing crescent moon, which will happen to be located in the middle of Cancer. You probably will not notice any of its associated stars, but what you will notice is a bright yellow-orange object positioned closely below the moon. That's not a star, however, but a planet: Mars.

If you haven't looked at it for a few months, you might be surprised, since Mars appears much dimmer now compared to back in mid-January, when it was so much closer to Earth. On Jan. 12, Mars was at its closest point to the Earth for 2025, 59.7 million miles (96.1 million km) away. At that time, Mars was shining practically as bright as Sirius, the brightest star in the sky. But now Mars has receded to a distance of 135 million miles (217 million km) from Earth, and consequently it now appears only one-ninth as bright. On Saturday evening, you'll see Mars sitting a little over one degree below the moon's southern limb.

And if you have binoculars, you'll also notice a splattering of tiny stars just off to the left of Mars, marking the heart of the crab and the star cluster that we had mentioned earlier.

Little Mist ... Big Star Cluster

Cancer's big star cluster is known formally as Messier 44 (M44), but is more popularly known as the "Beehive" or — by its somewhat less-popular moniker, "Praesepe" (PRY-suh-pee). The latter name extends back to ancient times and refers to a manger; a trough or box used to hold food for animals (as in a stable), mostly used in raising livestock. Known since antiquity, this swarm of stars can be seen as a hazy patch about one and a half degrees in diameter, provided that the sky is quite clear. To locate it, stretch an imaginary line from the 1st-magnitude star Pollux in the Gemini constellation to the similarly bright star Regulus in Leo. Your "beeline" will cut straight across the obscure stars of the Crab, passing just north of the Beehive.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Technically, the Beehive cluster shines as bright as a 3rd-magnitude star. First magnitude stars are among the brightest in the sky. The faintest stars visible to the eye are about 6th magnitude. (A star fainter than 4th magnitude generally is not visible in light polluted city skies). The star that joins the Big Dipper's handle with its bowl is known as Megrez and is 3rd magnitude and is fairly easy to see. However, the Beehive spans an area of sky some three times as wide as the full moon. Because its light is spread out, the cluster appears much dimmer than Megrez, and it can be a challenge to perceive using just your eyes. However, most deep-sky objects aren't visible to the unaided eye at all, though the Beehive is actually more noticeable than the more famous Andromeda Galaxy (M31).

Interestingly, the Beehive was also used in medieval times as a weather forecaster. It was one of the very few star clusters mentioned in antiquity. Aratus (around 260 BC) and Hipparchus (about 130 BC) called it the "Little Mist" or "Little Cloud." But Aratus also noted that on those occasions when the sky was seemingly clear, yet the "Little Mist" was invisible, that this meant that a storm was approaching.

Of course, we know today that prior to the arrival of any unsettled weather, high, thin cirrus clouds (composed of ice crystals) begin to appear in the sky; just a trace of cirrus can be generated from a warm front. Such clouds are thin enough to only slightly dim the sun, moon and brighter stars, but apparently just opaque enough to hide a dim patch of light like the Beehive. The ancients thus regarded its invisibility as a portent of impending precipitation.

Best views with binoculars and low power scopes

Want to see star clusters or Mars up close? The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of celestial objects. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review.

The Beehive remained a mysterious patch of light until Galileo directed his crude telescope toward it in the year 1610, and saw that it was a cluster of stars too dim to be separately visible to the unaided eye.

It's easy to see through binoculars from the city and in fact, you might be surprised to hear that your best views of the cluster will be binoculars or with a telescope employing low power. If you use 7-power binoculars, you'll be able to count at least a score of stars, but with a small telescope that offers a wide-field of view through a low-power eyepiece — say around 20-power — you'll be able to see as many as 60 stars, with some forming attractive pairs and geometric shapes.

But if you use higher powers, you'll lose the illusion of a cluster because the stars are spread over an area roughly three times the apparent diameter of the moon. It appears so large because of its relative closeness to us at a distance of between 520 and 610 light years away; closer to us than all but a few clusters.

Remember: if you're looking for a telescope or binoculars to observe star clusters like this one, our guides for the best binoculars deals and the best telescope deals now can help. Our guides on the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography can also help you prepare to capture the next skywatching sight.

Mars meets the Beehive

Mars is one of the swiftest moving objects in the sky. Except for the few months every two years when its closest to Earth, Mars moves through the stars at roughly a little more than a half-degree per day; roughly the apparent width of the moon, making it possible — though challenging — to track the planet's progress from one night to the next with your unaided eyes.

On Sunday night, May 4, Mars crosses the northern outskirts of the Beehive. Take note of how it will ever-so-slowly pass between two of the brightest stars in the cluster, 6.4-magnitude 39 Cancri to its south and 6.7-magnitude HIP42628 to its north. The best views will be along the West Coast where Mars will appear to align with these two stars at around 2 a.m. Pacific Time, though by then the planet and star cluster will be situated quite low to the west-northwest horizon.

Notice how, on Monday (May 5), Mars will have noticeably pulled away to the east of the Beehive, but both planet and cluster will still make for a very pretty sight in binoculars or a low-power telescope.

So, what should we call it?

Praesepe or Beehive? The choice is yours.

As to how the cluster's more popular name, "Beehive" evolved, it might be that some anonymous person might have exclaimed, when they saw so many tiny stars revealed through an early telescope, "It looks like a swarm of bees!" So "Beehive" is a relatively "new" title, dating back to perhaps the early 17th century.

From my own personal viewpoint, I always refer to the cluster by its older moniker, Praesepe, for this simple reason: Two nearby stars flanking the cluster on its eastern side, Gamma and Delta in Cancer, have been known for some 20 centuries by their respective proper names, Asellus Borealis and Asellus Australis — the Aselli or northern and southern ass colts — feeding from their manger (Praesepe). Centuries later, Christian skywatchers looked to Praesepe and its attendant stars as a celestial Nativity scene.

Although some might commonly associate these animals as stubborn, they actually have a keen sense of self-preservation and like to think about new things before they react, which is often misinterpreted as stubbornness.

Bonus! An eclipse of a star

In fact, on Saturday evening, a bonus: With binoculars and telescopes from the eastern half of the United States and Canada, the moon will appear to actually occult or hide the 4.7 magnitude star Asellus Borealis at around 10:30 p.m. (+/- 30 min.) Eastern Time (9:30 p.m. Central Time). The star will appear to abruptly vanish behind the moon's dark, unilluminated portion and then just as suddenly pop back into view about 45 minutes later (+/- 15 min.) from behind the moon's bright limb.

A precise timetable providing accurate Universal Times to the nearest second for the disappearance and reappearance of this star, for 386 selected locations, courtesy of the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) can be accessed here.

As an example: On the list of cities, Augusta, GA is #198. We see that Asellus Borealis will disappear behind the dark part of the moon's disk at 2:30 UT. Subtracting 4 hours, that translates to 10:30 p.m. EDT. As for the reappearance on the moon's bright side, that happens at 3:21 UT, which is 11:21 p.m. EDT.

So many things to see this weekend within the lowly Crab! I'll bet even Dr. Franklin would have been surprised at all the attention being accorded to his "empty space in the sky,"

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.