Could SpaceX and Boeing Spaceships Open a New Era for Space Tourism?

In front of a racous crowd at Johnson Space Center in Houston this month, NASA announced the nine astronauts who have been selected for the agency's commercial crew flights. The maiden crewed flights of SpaceX's Crew Dragon and Boeing's CST-100 Starliner vehicles may launch as soon as next year, marking the first time that astronauts have departed for space from U.S. soil since the space shuttle program ended in 2011.

"This is truly an exciting time for human spaceflight in our nation, and believe me — it's only going to get better as we charge off into our future," Bob Cabana, a former astronaut who is now director of NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, said during the Aug. 3 announcement. The only way it could get more exciting, he joked, was if he were selected himself.

Boeing's and SpaceX's work represents the culmination of a decade of effort from NASA, which has been trying to reduce its dependence on Russian Soyuz flights to the International Space Station (ISS). And space tourism companies are courting the spaceflight giants as well, hoping to bring tourists into space just behind the NASA astronauts. How close are we to getting there? [Photos: The First Space Tourists]

So how close are we to getting there? One industry analyst predicts that space tourism — an industry whose first official participant launched in 2001 — will resume again in the next 12 months.

"I think it's an exciting time for the industry, and today's announcement makes it even closer," Eric Stallmer, president of the Washington, D.C.-based Commercial Spaceflight Federation, told Space.com. "It's really setting in, the reality of it all. I think, as we see more NASA astronauts — American and international — going up on American vehicles, it shows the possibility and the desire that we have to have regular citizens going into space."

Years in the making

The world's first paying orbital space tourist was Dennis Tito, an American businessman who flew to the ISS in 2001 for the cool sum of $20 million. Only seven private citizens have ever paid out to make the trip to the ISS.

And before those paid ISS trips, only a fleeting few individuals launched on private space trips. In the early 1990s, Japanese journalist Toyohiro Akiyama and British chemist Helen Sharman flew to Russia's now-defunct Mir Space Station, but they did not pay for the flights themselves. (Akiyama's flight was funded by the Tokyo Broadcasting Service and Sharman won a contest sponsored by several British companies for her spot.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Some civilians flew on NASA shuttles in the 1980s and 90s as payload specialists, the most well-known being Christa McAuliffe, an elementary school teacher who died aboard the Challenger shuttle explosion in January 1986.

While these people went to space aboard government rockets, private industry wanted a ride of its own. Back in 2004, Sir Richard Branson founded Virgin Galactic shortly after the first nongovernmental crewed spacecraft, SpaceShipOne, became the first private spacecraft to make it into space twice. Branson wanted to send people into space as soon as 2007. Development delays with successor craft SpaceShipTwo, backed by Virgin Galactic — including a fatal crash in October 2014 that killed co-pilot Michael Alsbury and seriously injured pilot Peter Siebold during a test flight — pushed that hard deadline into a more gentle "to be determined."

Stallmer took on his current role just weeks after Virgin's fatal flight; he told Space.com that the SpaceShipTwo crash was one of the lowest lows in commercial spaceflight. But Virgin's lineup of paying customers hung on, for the most part, and Stallmer said the mood is more optimistic now.

"I know for sure there's about 800 people at Virgin Galactic that are itching to go and cannot wait for first flight," he said. "I also know that none of them are going to fly until they [Virgin] know they have the safest, most reliable vehicle. So safety is paramount, as it should be."

A constellation of commercial spaceflight providers

While Virgin was an early mover in prospective space tourism, a suite of others are in the game today. SpaceX was founded in 2002 on dreams to bring ordinary citizens to Mars. The company was determined to develop reusable rockets that could land by themselves after spaceflight — an unthinkable proposition at the time. But today, Falcon 9 rockets' first stagesregularly touch down to be used again later (though not all of the time). [Inside SpaceX's Epic Fly-Back Reusable-Rocket Landing (Infographic)]

Much more needs to be accomplished before humans can fly to Mars, but SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk regularly discusses possible human spaceflight concepts. He has said, for example, that paying Mars tourists will ride a giant rocket called BFR (allegedly "Big Falcon Rocket"). BFR should replace the entire Falcon line in the 2020s, he added. (The company also promised to send two passengers on a private trip around the moon, but that hasn't yet materialized.) And there's a growing market for tourism in other realms as well, such as near-space balloon rides by World View (which recently raised $26.5 million) and suborbital flights by Blue Origin, which hasalready built a prototype spacecraft.

Boeing's Starliner concept has attracted the attention of Bigelow Aerospace, a company with its own dreams of an inflatable space station for tourists. Bigelow tested two inflatable prototypes in orbit — Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 — starting in 2006 and 2007]. nThen, in April 2016, the company successfully launched an inflatable test room for the space station called the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module.

Bigelow's future space station may come online in the next few years, just as the commercial crew vehicles hit their stride in space. And other companies are jostling for space station launches in the near future as well, such as Houston-based Axiom Space, which wants to create a commercial space station, and space startup Orion Span, which wants to build a luxury hotel in orbit.

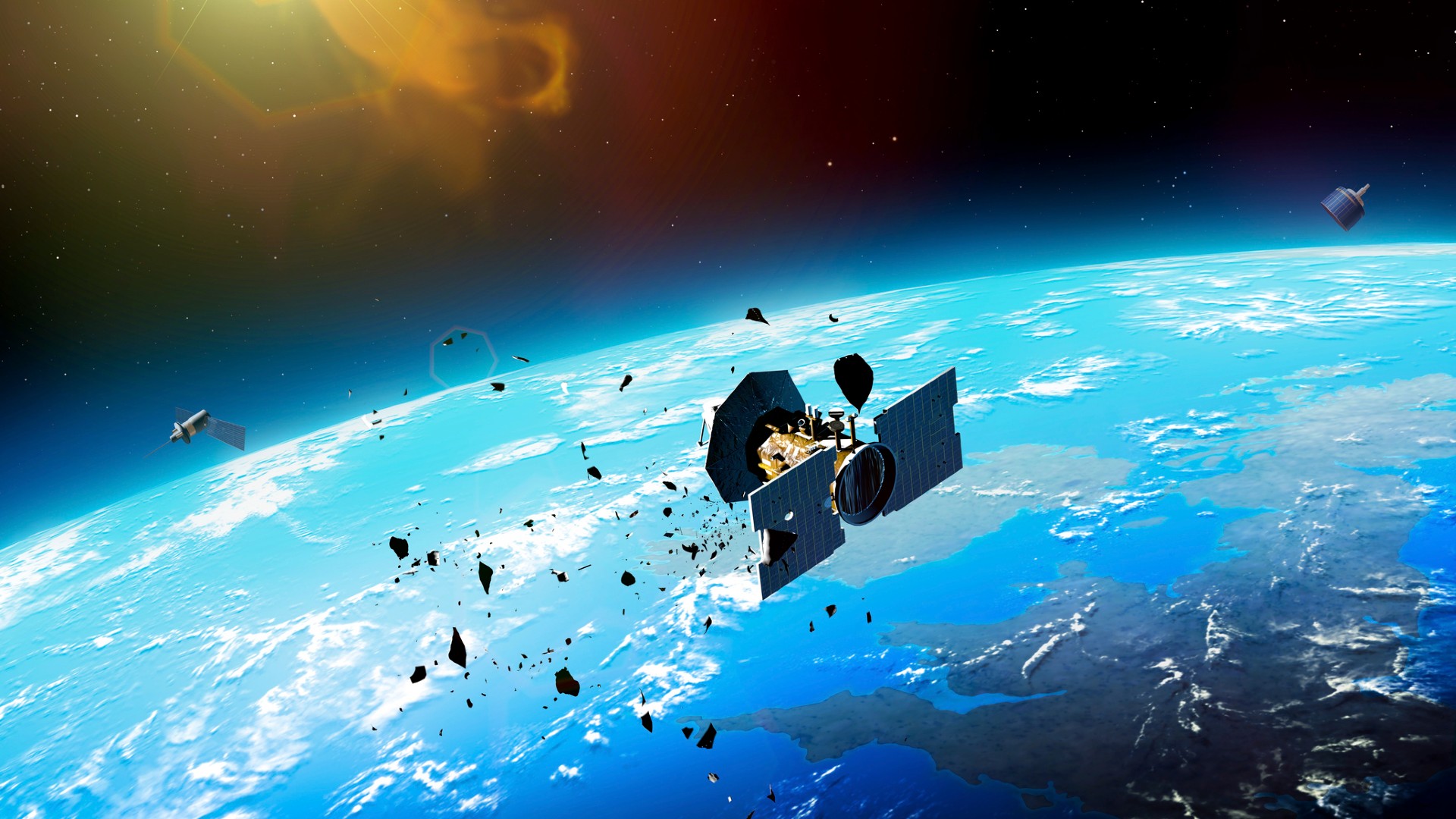

Stallmer said the recent proliferation of space tourism companies is not a coincidence. The commercial crew vehicles form part of a network of companies working to support one another in spacer. And it doesn't just extend to human spaceflight, he added; the increase in small satellites called cubesats in orbit led to the creation of several companies focused on small-scale launchers. Also, room for commercial experiments on the space station sparked a mini rush of companies focused on emerging markets, such as microgravity manufacturing.

It All the activity keeps Stallmer busy in his job at the Commercial Spaceflight Federation because there are so many commercial segments to work with, he said. "It's the whole ecosystem [of commercial space] that we are focusing on," Stallmer said, "and there's so much going on in all different aspects of the commercial marketplace."

Stallmer added that the industry is excited to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the July 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, an event that spurred so many young people back then to become the senior scientists and engineers of today. While the industry is disappointed that there wasn't rapid access to space after the Apollo missions, Stallmer said, today's excitement is helping to change that.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.