Bigelow Aerospace: Inflatable Modules for ISS

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Bigelow Aerospace is a firm focused on building inflatable space station modules. In January 2013, NASA announced that it would pay nearly $18 million for Bigelow to build a new room for the International Space Station. That room, called the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM), is expected to launch for a two-year mission in April 2016.

While Bigelow's visions for space stations and a moon base are still on the drawing board, the company already has two inflatable prototypes in orbit. Genesis 1 launched in July 2006, and Genesis 2 in June 2007. The company still watches over the prototypes to determine how they perform long-term.

Bigelow's inflatable modules are supposed to save on fuel costs when launching. Because the modules are lightweight and can expand in space, it takes less time and fuel to take the modules off the ground.

Legacy from 'satelloons'

Robert Bigelow, the founder of Bigelow Aerospace, took his inspiration from the earliest space missions by the United States. Although we are more used to thinking of satellites as solid metal structures, some of the first missions featured inflatable metallic balloons.

On Aug. 12, 1960, NASA launched Echo 1. Perched 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers) above Earth, this was the world's first inflatable satellite, and it facilitated the world's first live communication — a greeting from President Dwight Eisenhower — through a satellite. (Some dubbed these structures "satelloons".)

"Instantaneous global telecommunications fundamentally altered our lives, and this was the beginning of it," said former NASA chief historian Roger Launius in a 2010 Space.com interview. He was a senior curator in the space division at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Bigelow, as is common among space entrepreneurs, built up his fortune in other businesses — most notably, as founder of the Budget Suites of America chain of hotels.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As of 2010, the Economist reported that he had spent $180 million of his own funds on his company — "probably more than any other individual in history." Other reports from a few years ago say the entrepreneur is prepared to put up to $500 million by 2015.

He founded Bigelow Aerospace in 1998. Four years later, Bigelow Aerospace and NASA inked several Space Act pacts relating to employing technical workers. Bigelow subsequently signed several patent licensing agreements for NASA inflatable technology, and has paid royalty fees to the agency.

Two prototypes in orbit

In July 2006, a Dnepr rocket hefted Genesis 1 into orbit. "That's one small step for Bigelow ... one giant leap for entrepreneurial space," reported Mike Gold, corporate counsel for Bigelow Aerospace in Washington, D.C., at the time.

At the time, the company was aiming to fly six to 10 demonstration flights for the technology. Part of the cautious approach was to build up long-term information on how the structures would perform in space as they cope with radiation, micrometeoroids and other hazards.

Genesis 2 followed a year later. While the 15-foot (4.4-meter) spacecraft appears similar to Genesis 1, the module has different sensors and avionics to keep an eye on the spacecraft's pressure, temperature, radiation and attitude in orbit.

The company also flew personal items for customers under a "Fly Your Stuff" program, which allowed clients to send small items into space and get pictures of them from cameras on board. Some of the more unusual cargo included Madagascar hissing cockroaches and a Space Bingo game.

Bigelow had ambitious plans to fly several more modules, but the company has changed its plans in recent years. In 2007, it cancelled a planned Galaxy module amid "dramatic" rising launch costs. (Russian inflation and a falling U.S. dollar were among the factors cited.)

"Due to the fact that a high percentage of the systems Galaxy was meant to test can be effectively validated on a terrestrial basis, the technical value of launching the spacecraft — particularly after the successful launch of both Genesis 1 and 2 — is somewhat marginal," Bigelow statedat the time.

Instead, the company would pour more resources into the Sundancer, a module that it hoped to rate suitable for humans. With 180 cubic meters of habitable space, and its own life support system, the company hoped to send it into space as soon as 2010. The company later bypassed that in favor of doing a bigger module, the BA-330.

Aims for space station work

In December 2012, NASA and Bigelow signed a $17.8 million contract for Bigelow to fly the Bigelow Expanded Aerospace Module (BEAM) on the International Space Station.

BEAM will arrive at the station in April 2016, folded up and inside an unpressurized cargo hold in the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft. The module will measure 13 feet by 10.5 feet (4 meters by 3.2 meters) when fully extended.

NASA plans to use a robotic arm to put the module on an open berth of the station's Node 3 connecting module. When it's ready, astronauts in the station will activate it.

For at least the next two years, crews will measure temperature, pressure and radiation inside the module to gather data on its performance. Bigelow has said that this will likely be the quietest room inside the station.

"Using our patented expandable habitats, our plan is to greatly exceed the usable space of the International Space Station at a fraction of the cost by developing our next generation spacecraft," Bigelow stated on its website.

With the contract under its belt, Bigelow is hoping to use NASA's reputation in the aerospace community to generate more business.

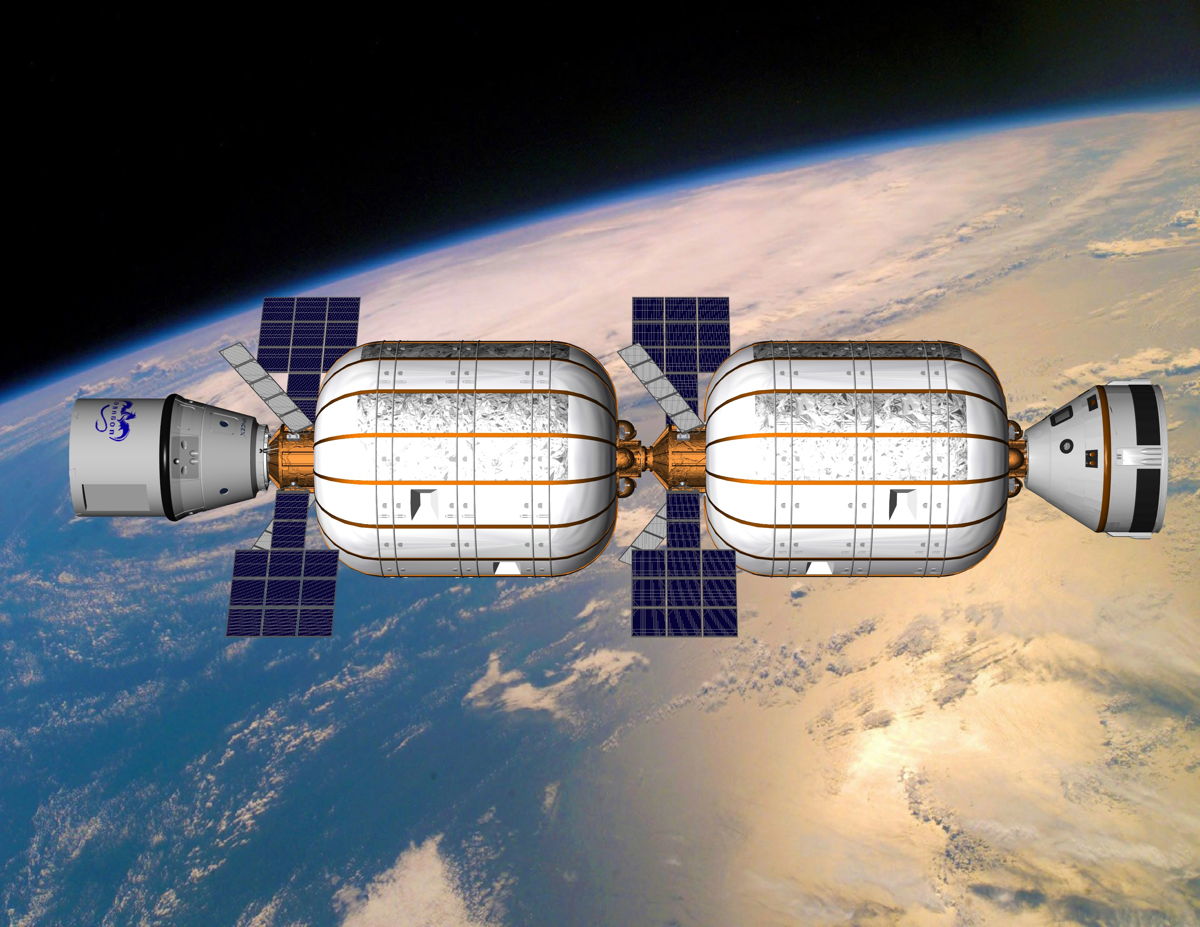

The company is busy developing the BA-330 habitat (so called because it includes 330 cubic meters, or 11,653 cubic feet, of usable volume inside.) It has signed memoranda of understanding with countries that may want to use the company's facilities.

Additionally, the company has partnerships with SpaceX and Boeing for the use of their Dragon and CST-100 spacecraft, respectively. These spacecraft would fly humans up to the future Bigelow stations.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.